Does 'Ban the Box' Help or Hurt Low-Skilled Workers?

Legislation to help convicts find jobs after release from prison is associated with reduced job-finding prospects for non-offending black and Hispanic young men without college degrees.

A person who can't get a job upon release from prison is more likely to break the law again. But employers don't want to hire ex-offenders—particularly those released recently—because as a group they are less prepared for work life, in worse health, and more likely to misbehave than non-offenders. One proposed way to help ex-offenders find employment and thereby reduce recidivism is "ban the box" (BTB) legislation that forbids employers from including a criminal-record check box on job applications. Because blacks and Hispanics are significantly more likely than whites to be incarcerated during their lifetimes, some BTB proponents claim that this legislation will also reduce racial disparities in employment.

That may not happen, however. In Does 'Ban the Box' Help or Hurt Low-Skilled Workers? Statistical Discrimination and Employment Outcomes When Criminal Histories Are Hidden (NBER Working Paper 22469), Jennifer L. Doleac and Benjamin Hansen conclude that BTB policies actually reduce work opportunities for young, low-skilled black and Hispanic men with clean records.

"Advocates for these policies seem to think that in the absence of information, employers will assume the best about all job applicants," the researchers write. "This is often not the case." Instead, they report that employers who want to avoid hiring recently incarcerated individuals appear to adopt a strategy of statistical discrimination when denied data about applicants' criminal records: They curtail their interviewing of candidates in demographic groups that contain the greatest numbers of recently released ex-offenders—young, low-skilled, non-college-educated black and Hispanic men.

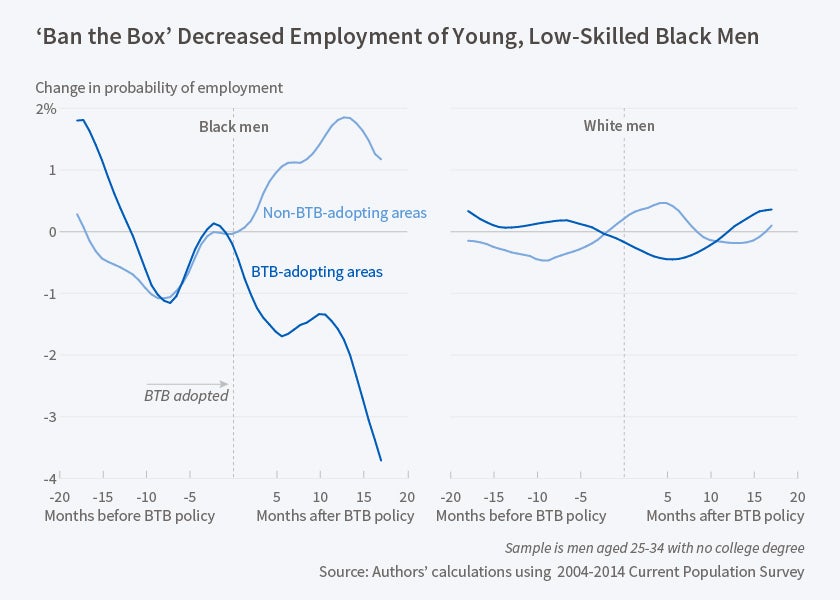

The researchers analyze individual-level data from the monthly U.S. Current Population Survey from 2004 to 2014 to explore the impact of state and local BTB policies on the probability of employment for black and Hispanic men aged 25-34 without college degrees. Using variation in when different jurisdictions adopted BTB laws to measure employment effects, they conclude that BTB legislation reduced the probability of employment by 5.1 percent among black men and 2.9 percent among Hispanic men.

The size of the BTB effect was smaller in areas of the country where these groups constituted a larger share of the population (the South for blacks, the West for Hispanics), and larger elsewhere. BTB reduced black men's employment probabilities by 7.4 percent in the Northeast, 7.5 percent in the Midwest, and 8.8 percent in the West; similar, albeit lesser, effects were seen for Hispanic men in the Northeast, Midwest, and South.

"These results suggest that the larger the black or Hispanic population, the less likely employers are to use race/ethnicity as a proxy for criminality," the researchers write. The effect also increased when unemployment rates were high. Employment probabilities increased significantly under BTB for highly educated black women and for older, low-skilled black men. Positive but statistically insignificant effects were also seen for whites.

These results are consistent with numerous other studies that have examined the effects of limiting employers' information about employees. "Policymakers cannot simply wish away employers' concerns about hiring those with criminal records," the researchers conclude. "Policies that directly address those concerns—for instance, by providing more information about job applicants with records, or improving the average ex-offender's job-readiness—could have greater benefits without the unintended consequences found here."

—Deborah Kreuze