Explaining the Good Fortune of Dragon Year Children

Those born in a Year of the Dragon are more likely than others to obtain a bachelor’s degree or higher — because parents invest more in them.

Is a child born in a certain zodiac year really destined to have more good fortune and success in life than a child born in another year? Many parents in China believe that’s the case for children born in a Year of the Dragon, and some education statistics would appear to confirm it.

But in Can Superstition Create a Self-Fulfilling Prophecy? School Outcomes of Dragon Children in China (NBER Working Paper No. 23709) Naci H. Mocan, and Han Yu show that the higher educational achievements of Dragon year children in China are largely due to the much higher expectations of their parents. Some parents time marriages so as to have children born in Dragon years, and many of them invest more time and money in their children than other parents, thereby helping to fulfill their lofty expectations.

In Chinese astrology, one of the oldest horoscope systems in the world, each year in a 12-year cycle is represented by an animal, and there is widespread popular belief that individuals born in different zodiac years are inherently different. Those born in a Year of the Dragon supposedly are destined for good fortune and greatness. Previous studies of a number of Asian cultures have shown that fertility rates increase in Dragon years.

Previous studies of the educational achievements of Dragon year children produced mixed results. Some showed no effects, and others found negative educational effects, leading to speculation that higher birth rates in Dragon years actually harm children who are subsequently exposed to larger classroom sizes and more competition for college and job openings.

In this study, the researchers analyze data about marriages, births, demographic backgrounds of children and their families, school test scores, college entrance exam results, family surveys, and other information from sources including the China Health Statistical Yearbook, the China Civil Affairs Statistical Yearbook, the China General Social Survey, the Beijing College Students Panel Survey, and the China Education Panel Survey.

After adjusting their data to account for the differences between zodiac and Gregorian calendar years, they find spikes in Chinese marriages in the two years prior to the most recent Dragon years: 2000 and 2012. Both Dragon years saw birth rate increases. Live births increased by 289,224 in 2000 compared to the year prior, and by 935,854 in 2012 compared to 2011. Conversely, the researchers find a sharp decrease of more than 400,000 births in 2003, the Year of the Sheep, an unfavorable year for births in the Chinese astrological system. Children born in a Dragon year were 14 percent more likely than children born under the other 11 signs to obtain a bachelor's degree or higher. Those born in Dragon years also scored higher on college entrance exams and middle school tests.

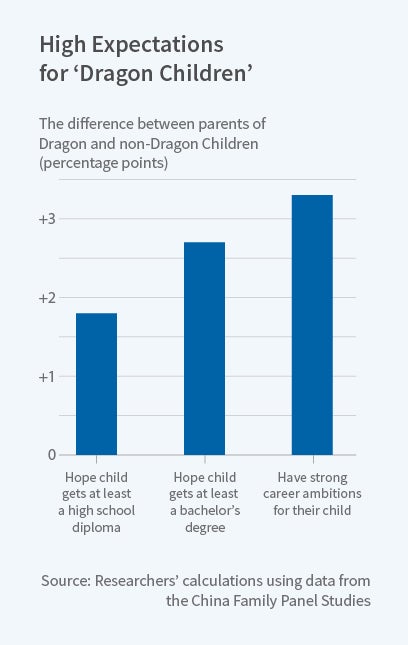

Differing income and educational levels of parents cannot explain the higher educational achievements of Dragon year children. However, in analyzing government surveys of parents, the researchers find that mothers and fathers of Dragon year students have consistently higher expectations for their children than do parents of children born in other years. Moreover, the parents report investing more time, money, and effort into making sure their Dragon-year children succeed — and even provide them with more pocket money and require them to do fewer household chores, presumably so they can focus more on school work.

"Even though neither the Dragon children nor their families are inherently different from other children and families, the belief in the prophecy of success and the ensuing investment become self-fulfilling," the researchers conclude.

— Jay Fitzgerald