Do Private Equity Funds Manipulate Reported Returns?

Underperformers may overstate interim returns, while high performers may be conservative in valuing their unrealized investment valuations.

When it's time to raise money for a new fund, some private equity general partners (GPs) appear to manipulate the net asset value (NAV) of their current funds.

Some poor performers appear to overstate their NAVs, while funds at the top of the scale actually understate the net value of their funds, according to research by Gregory W. Brown, Oleg R. Gredil, and Steven N. Kaplan. They report these findings in Do Private Equity Funds Manipulate Reported Returns? (NBER Working Paper 22493). They also find that institutional investors usually see through the machinations.

"Overall, our results indicate that overstating interim returns has not been a winning strategy for GPs on average," the researchers report. "While current fund performance impacts the odds of a successful fundraising, aggressive NAV marks are associated with a lower probability of raising a next fund. Consequently, GPs who are not underperforming should have an incentive to be truthful, or even conservative, with their unrealized investment valuations."

When external investors, the limited partners, are considering committing capital to a new private equity fund, they do not know what investments the GPs will select and must rely on observable metrics, including the GPs' success in running current funds, in making their decisions.

Using data on more than 200 investment programs, including pension funds, endowments, foundations, and institutional investors, as well as a database of 12,545 U.S. dollar-denominated private equity firms between 1969 and 2016, the researchers look for tell-tale biases in the funds' NAVs.

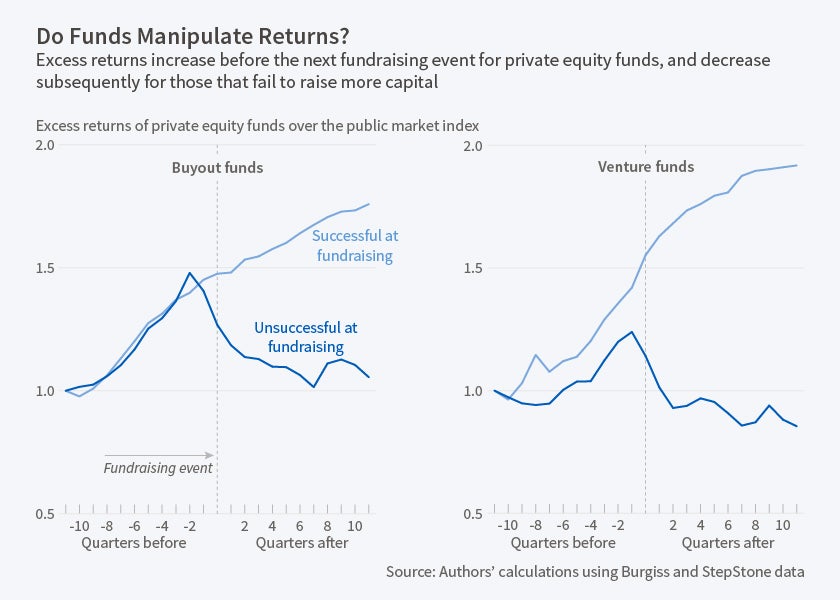

For example, if a GP inflates an existing fund's NAV while raising money for a new fund, then at some point that fund's performance will fall when investors cash out and discover the exaggeration. The researchers examine returns around the time a firm begins raising money for a new fund, or, absent a new fund, near the end of the current fund's term, when, presumably, a GP would be considering the creation of a successor fund. They find that performance of average buyout and venture funds falls around these events. Then, they calculate the probability of fundraising success based on excess returns and distributions to investors. They find that during the period when GPs are making a final push to attract investors to a new fund, the excess returns of their current funds rise. These returns fall in the final years of the funds.

"This evidence is suggestive of attempts at manipulation that are not successful since investors are not willing to commit to a next fund," the researchers say.

—Laurent Belsie