Why Some Regions Rebounded Faster after the Great Recession

Frictions in financial intermediation in some regions may have slowed recovery by limiting consumer access to lower interest rates and refinancing opportunities.

During the Great Recession, the United States experienced an estimated 6 million foreclosures, a steep rise in unemployment, and a sharp decline in consumer spending. The federal government responded with several programs intended to help distressed homeowners, and the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates in an effort to stimulate the economy.

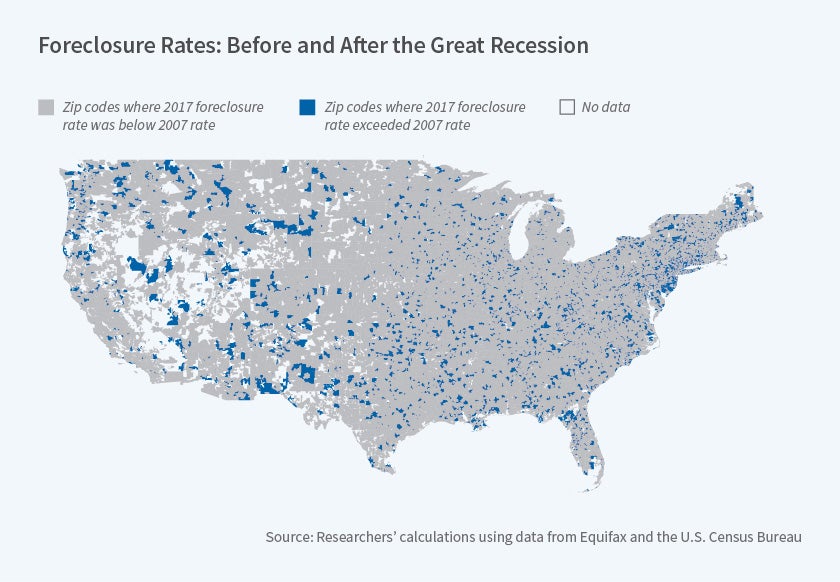

The extent of the downturn varied substantially across regions. Housing prices, for example, fell sharply in some metropolitan areas, and more modestly in others. This pattern was also evident in the recovery. After the economy hit bottom, some areas of the country experienced far swifter recovery than others. In Debt Relief and Slow Recovery: A Decade after Lehman, (NBER Working Paper 25403), Tomasz Piskorski and Amit Seru examine regional variation in the recovery of house prices, consumption, and employment. Even by the end of 2017, they find, half of the zip codes in the U.S. had not returned to the pre-recession levels of these three measures. Why?

The researchers construct a novel dataset that allows them to identify mortgage default, foreclosure, homeownership, mobility, and durable spending patterns at the individual, regional, and aggregate levels, using a representative sample of more than 13.5 million active consumers drawn from credit-reporting agency Equifax’s data. The dataset follows these consumers from the end of the second quarter of 2007 through the end of the fourth quarter of 2017. By combining the Equifax data on delinquency rates, foreclosure rates, homeownership, mobility, income, and other individual information, with regional data on employment, house prices, and durable spending, the researchers explore the factors that correlate with differences in recovery patterns.

They find that of the six million foreclosures in the decade after the onset of the Great Recession, 25 percent were associated with owners of multiple homes. These owners comprised only 13 percent of the market. Many foreclosures displaced homeowners, with most of them moving at least once. Only a quarter of foreclosed households regained homeownership, taking an average of four years to do so.

The primary focus of the study is explaining the regional differences in recovery patterns over the last decade. Some of the variation can be chalked up to predictable factors. For example, homes were more likely to be foreclosed for buyers with larger mortgages, lower credit scores, and lower incomes. Consumers living in zip codes with higher unemployment rates, lower shares of people with a college education, and lower home prices were more likely to become delinquent on their mortgages. But these factors don't explain everything. The researchers also find that features of a local economy's banking, mortgage, and credit markets — its "financial intermediation sector" — are associated with the speed of its recovery.

They identify several important features of the financial intermediation sector. One is mortgage contract rigidity — whether a mortgage was fixed-rate or adjustable. A second is constraints on refinancing, in particular whether eligibility requirements limited the set of homeowners who could refinance to take advantage of low interest rates. A third is the capacity of loan servicers to renegotiate troubled loans. In areas with a higher fraction of fixed-rate mortgages, with tighter constraints on refinancing, and with less lender capacity to renegotiate loans, the recovery was slower. Borrowers in these areas did not receive the benefits of lower interest rates and debt relief as quickly as borrowers in other areas. When these forms of relief were more available, they helped mortgage borrowers to stay in their homes.

Overall, the extent and speed of recovery is strongly related to frictions in the intermediation sector. The researchers conclude that the crisis could have been "much less severe if some specific frictions in the financial intermediation sector affecting the pass-through of lower rates and debt relief measures had been alleviated."

The results highlight the role of the financial intermediation sector when designing debt relief policies in the wake of a housing crash. They have potential implications for mortgage market design, monetary policy pass-through, and macroprudential policy interventions.

— Anna Louie Sussman