When the Wheat Harvest and the Fracking Boom Rode the Rails

Consumers bore most of the costs when expansion of fracking activity stressed the capacity of railroads to transport North Dakota's grain harvest.

North Dakota produces between 250 and 300 million bushels of hard red spring wheat each year, about half of the U.S. harvest. It produces 300 to 400 million bushels of corn and 150 to 200 million bushels of soybeans.

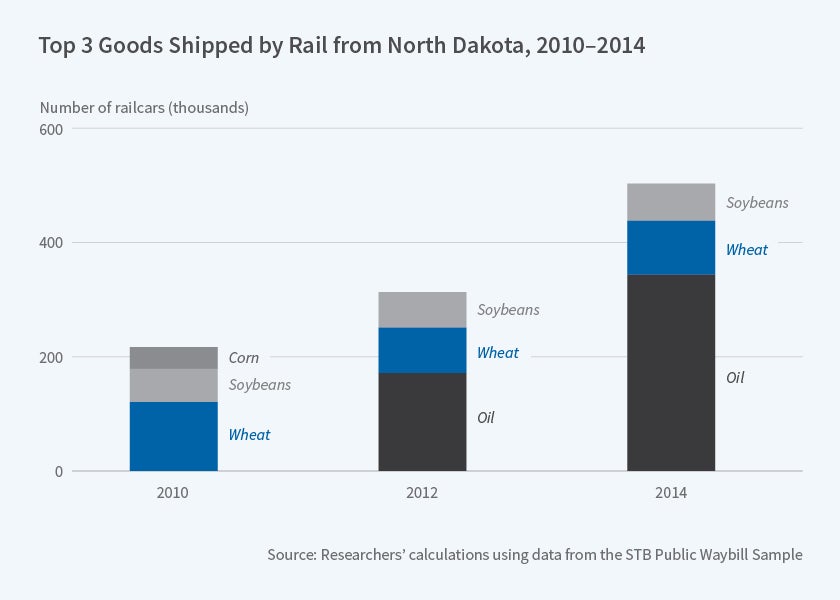

In Food vs. Fuel? Impacts of Petroleum Shipments on Agricultural Prices (NBER Working Paper No. 23924) James B. Bushnell, Jonathan E. Hughes, and Aaron Smith examine how markets adjusted when the railroads that traditionally handle North Dakota's vast grain harvest faced an unexpected surge in shipping demand from oil producers in the state's Williston Basin. From 2010 to 2014, while total shipments of grain remained relatively constant, oil shipments increased from 26,000 railcars to over 343,000 per year. At the end of that period, oil represented about half of total rail shipments.

The greater demand for transporting oil led to rail network congestion, long shipping delays, and higher spoilage rates and storage costs. The new study finds that the costs of these developments were borne mainly by consumers, rather than farmers. The wheat spread — the difference between the price paid for wheat delivered to local elevators by farmers and the price paid for wheat in commercial hubs like Minneapolis — increased from $1.49 per bushel in 2012 to $2.59 per bushel in 2014.

North Dakota grain shipments have historically traveled under rail rates determined by the system of public common carriage tariffs. These take-it-or-leave-it rail rates are available to any shipper on a first come, first served basis. Railroads must provide a 20-day notice before they can adjust these rates, which are subject to cost-based regulatory oversight. These rates do not include a guaranteed delivery time. The researchers note they are "poorly suited to allocating resources to customers with varying delivery priorities." For each increase of 10,000 oil carloads per month, regulated rail rates for wheat shipments rose by $0.06 to $0.11 per bushel, a small fraction of the total $0.35 to $0.49 increase in spread associated with similar carload increases.

How do markets allocate suddenly scarce transportation when regulated prices change slowly? Some railroads used "railcar auctions," in which a successful bid guarantees that a railcar will be delivered for loading during a specified time window. Shippers pay the common carriage tariffs plus a premium for delivery priority. As oil shipments increased, so did 2013–14 railcar auction prices for the railroads serving North Dakota. Their increase was highly correlated with the changes in the wheat spread, rising to "levels that could account for the entire increase in spread during the period," the researchers found.

After controlling for diesel prices, the weather, total freight demand, and the size of the harvest, the researchers conclude that "railcar auctions were used as a mechanism to allocate scarce capacity to the customers with the highest willingness to pay for it." Some of those customers — the ones who outbid competing grain shippers — were "flour millers in Minneapolis [who] were prepared to pay a premium to avoid supply disruptions." Congestion created by oil shipments traveling on the tracks traditionally used for wheat thus appears to have raised grain transportation costs which were in turn largely absorbed by grain purchasers.

— Linda Gorman