Efforts to Curb Tax Avoidance Offshore Paid Off, to a Degree

Recent enforcement initiatives increased reported capital income by $2.5 to $4 billion annually, yielding between $700 million and $1 billion in tax revenue.

In 2008, the United States government launched a number of enforcement initiatives to rein in its residents' use of secret offshore accounts to avoid their tax liabilities. Through several high-profile lawsuits, the U.S. forced a number of Swiss banks, including UBS, the largest Swiss banking institution, to share account information about U.S. customers. By threatening sanctions, the U.S. also compelled widely recognized tax haven countries — including Switzerland, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, and Panama — to accept information exchange agreements that allow the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to request and receive account information about persons suspected of tax evasion. Finally, the IRS established several "voluntary disclosure" programs offering account holders a temporary window during which they could disclose their offshore accounts without risking criminal penalties.

Niels Johannesen, Patrick Langetieg, Daniel Reck, Max Risch, and Joel Slemrod explore the effects of these enforcement initiatives in Taxing Hidden Wealth: The Consequences of U.S. Enforcement Initiatives on Evasive Foreign Accounts (NBER Working Paper No. 24366).

The enforcement initiatives raised tax revenues: Annual reported capital income rose by $2.5 to $4 billion annually, corresponding to between $700 million and $1 billion in annual tax revenue. The researchers characterize these sums as "sizable, but...small relative to independent estimates of the amount of concealed offshore wealth and capital income overall." A recent study by Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman (NBER Working Paper No. 23805) estimated the amount held offshore by U.S. households at $1 trillion.

The authors of Taxing Hidden Wealth use several datasets on income, foreign bank accounts, and participation in the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure program. They first document a surge in the number of U.S. taxpayers reporting a foreign bank account after the initiatives were implemented. Between 2005 and 2008, an average of about 45,000 U.S. residents reported a foreign account for the first time by filing a Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR). In 2009, by contrast, there were 105,000 such first-time FBAR filers.

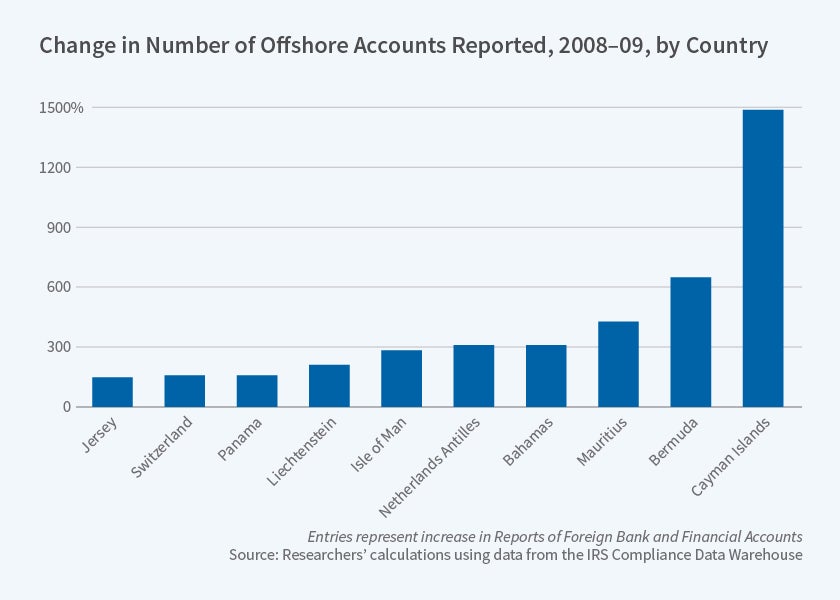

This dramatic increase, the researchers write, "is suggestive that a large number of taxpayers — a simple difference estimate would be around 60,000 individuals — disclosed previously unreported foreign accounts in response to the new enforcement policies." This theory is supported by another finding: the increase in account filings was especially large for accounts more likely to be used for tax evasion — those located in traditional tax haven countries and those containing over $1 million. In 2008, for example, there were only 300 FBAR filings for accounts in the Cayman Islands; in 2009, there were 4,500. The researchers estimate that, all in, "the combined value of the accounts disclosed because of the enforcement efforts was just below $120 billion."

The study found that only 15,000 of the first-time FBAR filers used the voluntary disclosure program in 2009; the rest filed "quietly," a strategy which allowed account holders to avoid back taxes or financial penalties but left them exposed to criminal penalties.

The researchers found an increase in taxable capital income among both first-time FBAR filers using the voluntary disclosure program and those not using the program, which suggests that the latter group included many quiet disclosers who reported accounts in response to the new enforcement initiatives, while still avoiding an admission of tax evasion. Among first-time filers, account holders who used the voluntary disclosure program were more likely to disclose larger amounts and to disclose Swiss accounts. This suggests that taxpayers chose to participate in the voluntary disclosure program when they believed they faced a higher risk of detection and prosecution.

— Dwyer Gunn