Can an Increase in Government Spending Lower Local Interest Rates?

Rising Department of Defense outlays in a community are associated with lower auto and home equity loan rates, perhaps because they increase expected future income and wealth.

Textbook macroeconomic theory holds that unless there are slack resources in the economy, an increase in government spending will put upward pressure on interest rates, thereby lowering consumer spending and business investment. But new empirical findings suggest that, at least at the local level, higher government spending actually may lead to a decline in interest rates.

In Effects of Fiscal Policy on Credit Markets (NBER Working Paper 26655), Alan J. Auerbach, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Daniel Murphy find that fiscal stimulus can not only expand output but can also contribute to lowering the cost of credit. They conclude that fiscal policy may therefore be able to push rates lower when monetary stimulus is constrained by interest rates at already-low levels raise, but also collected a compensation premium for having accepted a risky, lower-paying contract initially. This deferred-pay effect created more, a channel of fiscal policy transmission that has not been emphasized previously.

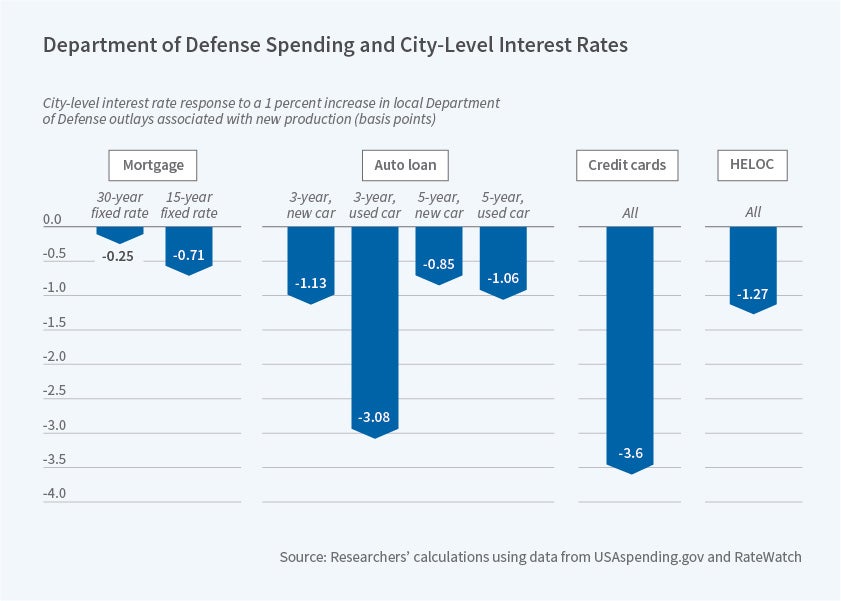

The researchers examine the effect of US Department of Defense (DOD) contracts on the interest rates prevailing in the cities in which the contract work was performed. Although US credit markets are integrated, local banks set their own rates for consumer loans. The researchers find that a 1 percent increase in expected DOD outlays from ongoing contracts, which may be interpreted as an injection of liquidity, is associated with a 0.24 basis point reduction in auto loan rates and a 0.30 basis point reduction in the rates charged for home equity lines of credit with a high loan-to-value ratio. In contrast, outlays associated with new production contracts have interest rate effects on auto loans that are an order of magnitude higher, with rates declining by 1.26 basis points in response to a 1 percent increase. The effect of new contracts on mortgage loan rates was small, and there was no statistically significant effect on credit card rates.

Outlays for new DOD production may raise the expected future income and wealth of city residents, which could in turn reduce default risk and hence the risk premium charged for riskier loans. This would be a more significant consideration for loans backed by riskier, less marketable collateral. In fact, a 1 percent increase in DOD outlays for new production reduced rates for riskier, less marketable, short-term used car loans by 3.08 basis points while reducing short-term loan rates for new cars by only 1.13 basis points.

The researchers suggest that their findings are explained by the notion that government spending relaxes credit markets through a liquidity injection and by reducing the perceived riskiness of borrowers. Even if an increase in outlays on a prior contract was expected, it could nevertheless represent an ongoing injection of liquidity into the local economy. As the earnings of local contractors rise, whether because of old or new outlays, local borrowers may become more creditworthy. Local banks may make more loans, their balance sheets may improve, and credit may expand along with their lending.

—Linda Gorman