Test-Related Stress and Student Scores on High-Stakes Exams

Standardized tests are widely used to gauge student capabilities and inform educational programming. Test scores can also shape the academic destinies and careers of students. Their importance can generate stress among test-takers.

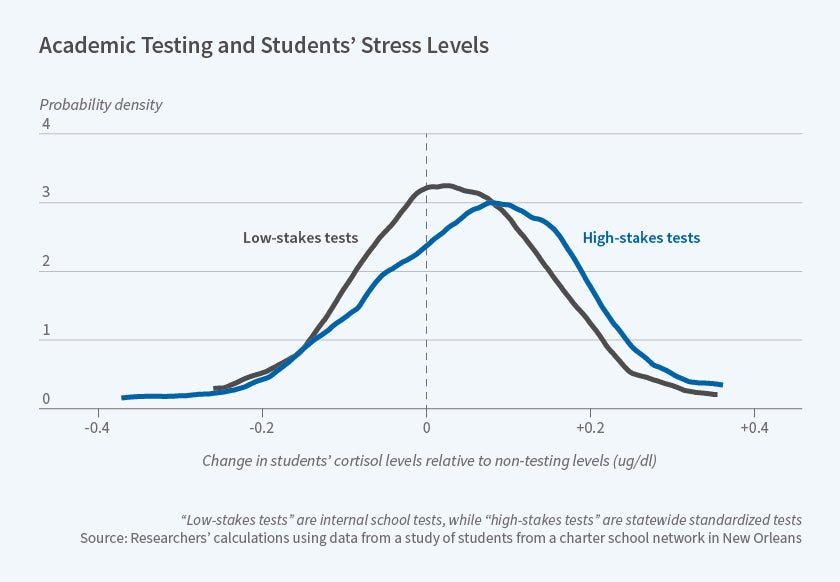

In Testing, Stress, and Performance: How Students Respond Physiologically to High-Stakes Testing (NBER Working Paper 25305), Jennifer A. Heissel, Emma K. Adam, Jennifer L. Doleac, David N. Figlio, and Jonathan Meer document that students' level of a stress hormone, cortisol, rises by about 15 percent on average in the week when high-stakes standardized tests are given.

The study analyzes administrative data, student diaries, and saliva samples of New Orleans students in grades 3-8 in the 2015-16 academic year. Most students in the study were low-income African Americans, but they hailed from different areas of the city, with different levels of wealth and crime. The students took saliva samples during different periods of the year, which allowed the researchers to compare cortisol levels in weeks with and without high-stakes tests.

The increase in cortisol in test weeks is largely the result of a sharp increase — 35 percent on average — for male students. There are no substantial changes for females between testing weeks and other weeks. The researchers also find larger increases in cortisol for students from neighborhoods with higher poverty rates, and larger numbers of 911 calls, although the evidence is not conclusive.

Large spikes in cortisol levels can lead to a lack of focus, recall, and ability to perform tasks. The researchers compare the test scores of students who showed a cortisol increase or decrease of more than 10 percent in the test week relative to the no-test week, and those whose cortisol level was similar across weeks, controlling for expected academic performance. Such a rise or fall in cortisol is associated with a 0.4 standard deviation decrease in the test scores — the equivalent of a drop of approximately 80 points on the 1600-point SAT scale. These findings suggest that for some students, physiological reactions to test-taking may diminish their scores.

— Jay Fitzgerald