Employees See Wage Gains when Small Firms Win Patents

The increase is concentrated among earners in the top quartile of the firm's wage distribution, and those who were employed by the firm during the year of the patent application who stayed on in subsequent years.

Whether workers' wages are mostly determined by the value of what they contribute to the firm they work for, with little room for negotiation, or whether they in substantial part reflect a division of profits, or "rents," between the two parties, is a long-standing and fundamental question in labor economics. There is substantial variation in the wages that workers with similar characteristics, as measured on economic surveys, earn at different firms. A growing body of research suggests that such inter-firm wage differences are an important contributor to overall wage dispersion in the U.S. economy.

In Who Profits from Patents? Rent-Sharing at Innovative Firms (NBER Working Paper 25245), Patrick Kline, Neviana Petkova, Heidi Williams, and Owen Zidar examine how worker compensation relates to firm performance before and after a firm is awarded a patent. They compare worker outcomes at firms whose patent applications were initially accepted to outcomes at firms whose applications were initially rejected.

The researchers find that firms granted high-value patents enjoy rapid increases in size and improvements in performance. A top-quintile patent is associated with a 22 percent expansion and about $37,000 in additional revenue for each worker at the time of the patent award. Average earnings rise by approximately $3,700 per employee per year; worker pay plus the company's earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation rise by about $12,400 per employee.

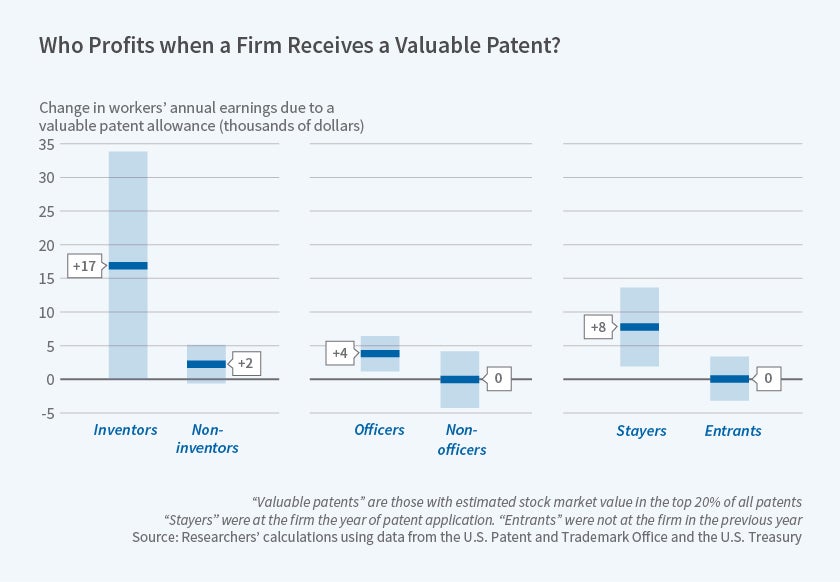

This increase in employee earnings is concentrated among earners in the top quartile of the firm's wage distribution, and among workers who were employed by the firm during the year of the patent application and remained at the firm in subsequent years. These "stayers" enjoy an earnings boost of about $8,000 per year after the initial patent allowance, while employees who leave see no such boost. Inventors see their earnings increase by $17,000 a year, while non-inventors see only a $2,000 boost.

One way of quantifying the magnitude of these estimates is to say that a $1 increase in surplus due to a patent award results in a 61 cent average earnings increase for stayers and a 29 cent increase for all workers. Worker retention rates also increase more among the groups of workers that enjoy the largest earnings boost.

The researchers conclude that their findings are consistent with the theory that employers engage in rent-sharing, passing some of the economic rents produced by high-value patents through to workers, with the most valuable workers — those who would be most expensive to replace — capturing the largest proportion of these gains.

— Dwyer Gunn