Confiscation of German Copyrights Boosted US Math and Science

WWII-era Book Republication Program lowered prices for German books, facilitating a broad geographical diffusion and utilization of the information in these volumes.

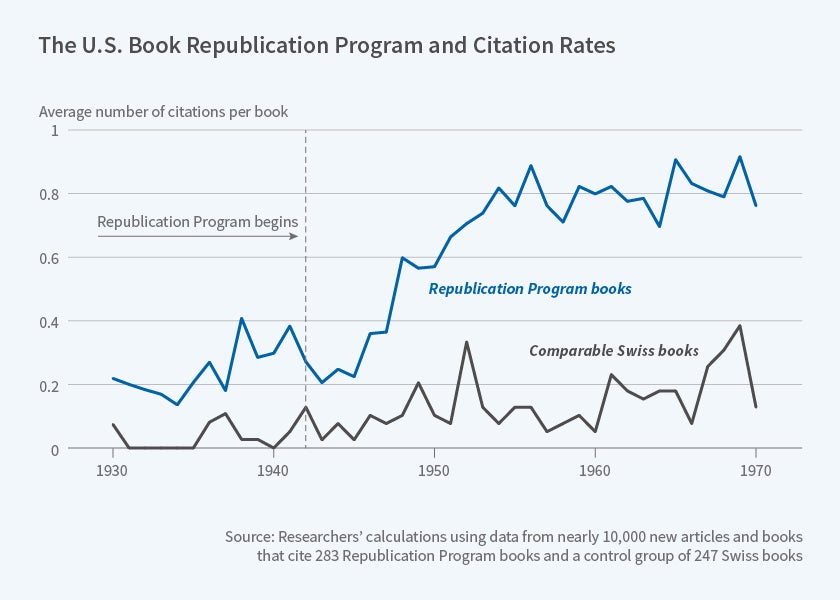

In Effects of Copyrights on Science — Evidence from the U.S. Book Republication Program (NBER Working Paper No. 24255), Barbara Biasi and Petra Moser estimate the welfare costs of long-lived copyrights in fields in which new advances depend critically on access to existing work. They do this by tracking the 1920 to 1970 English-language citation rates for 283 German-language chemistry and mathematics books affected by President Franklin Roosevelt's executive order of July 6, 1942, confiscating the copyrights protecting more than 100,000 German book titles. U.S. publishers were given the chance to bid for six-month licenses to republish the German books under the U.S. Book Republication Program (BRP).

At a time when most U.S. scientists could read German, publishers began producing exact copies of important German science books. Prices fell by an average of 25 percent, and in some cases by much more. For example, Springer, a major German publisher, had sold the set of Frederick Konrad Beilstein's Handbuch der Organischen Chemie for $2,000; U.S. publishers sold the same set for $400. In addition to tracking citation rates and costs, the researchers measure the books' rate of diffusion in U.S. library holdings, their role in U.S. patents, and the growth in the number of new U.S. mathematics PhDs.

They find that each 10 percent decline in the price of an affected book was associated with a 43 percent increase in citations. They conclude that the change in copyright policy raised English-language citations to BRP books by 67 percent. A 10 percent decline in a book's price produced an additional 88 percent increase in citations for mathematics compared with chemistry. The difference may stem from the fact that while knowledge creation in mathematics depends primarily on human capital, chemists also require equipment, chemicals, and lab space.

The lower prices of BRP books encouraged their purchase by libraries that were not affluent enough to acquire the books at the prices charged by the German publishers. Dates on the library lending cards in 127 of the BRP books in the Stanford University Library, for example, suggest that loans began around 1941 and peaked around 1955. These dates correspond well with the temporal pattern of increasing citations. The growth in the number of mathematics PhDs also corresponds well with BRP book availability. Locations within 25 miles of a copy of a BRP book produced almost 0.8 more mathematics PhDs per year after 1942 than before. Citations to BRP books within patents increased by 15 percent.

Swiss scientists were also leaders in chemistry and mathematics, and many Swiss scientists published in German. But because Switzerland was neutral, Swiss publishers retained their copyrights in the United States and their book prices remained high. Few copies were available outside of libraries at Yale, Harvard, the University of Illinois, and the New York and Chicago public library systems. The trends in Swiss and German citations were comparable until 1942 but they diverged after the BRP program began, with citations to German works rising more quickly.

The researchers note that their findings highlight a key tradeoff for intellectual property rights. Although copyrights provide an incentive for people to publish books, long-lived copyrights in fields that depend on access to existing work can produce large welfare losses. These distortions may be particularly important in scientific publishing, where the incentive effects of copyright are likely to be relatively small.

— Linda Gorman