Results of Texas’s Experiment in Increasing College Diversity

Texas’s Top 10 Percent rule raised college attendance, graduation, and earnings for students from underrepresented high schools who gained access to UT Austin but did not reduce these metrics for those who were crowded out.

Selective college admissions are fundamentally a question of tradeoffs: given capacity, admitting one student means rejecting another. However, despite numerous changes in admissions policies, including changes in the ability of states to use affirmative action in admissions, a key unresolved question is how changes in admissions policies affect the students who gain or lose spots at particular universities as a result.

In Winners and Losers? The Effect of Gaining and Losing Access to Selective Colleges on Education and Labor Market Outcomes (NBER Working Paper 26821), Sandra E. Black, Jeffrey T. Denning, and Jesse Rothstein explore the effects of attending an elite institution on both those who are newly admitted and those who are pushed out by the introduction of the Texas Top 10 Percent rule.

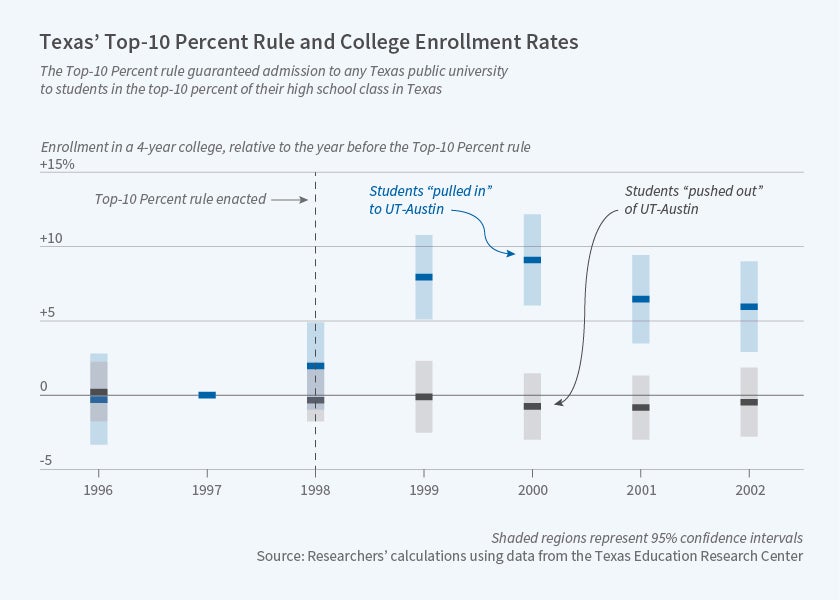

In 1997, Texas established the Texas Top 10 Percent (TTP) rule after the state’s affirmative action program was struck down by a court ruling. Under the rule, any Texas students in the top 10 percent of their high school class were guaranteed admission to any of the state’s public universities, including the University of Texas at Austin, the system’s prestigious flagship. The researchers analyze how this policy change affected educational and labor market outcomes for two different groups of students that graduated from high school between 1998 and 2002: those “pulled in” to UT Austin by the policy — students who could attend UT Austin as a result of the policy, but would not have been likely to do so in the absence of the policy — and those “pushed out” — students who were not admitted but could have been before TTP.

The researchers first compared the demographics of the two groups. Proponents of TTP suggested that the pulled-in group would consist of high-performing students from schools that historically had not sent many graduates to UT Austin. Indeed, the pulled-in students had higher test scores and had taken more AP classes than pushed out ones. The pulled-in group also was more racially diverse and from lower-performing schools with higher shares of minority and low-income students.

The TTP rule had meaningful positive effects on pulled-in students, who were about 6.6 percentage points more likely to attend a public four-year college in the state and 5.3 percentage points more likely to attend UT Austin after TTP came into force. These students attended better colleges in general, as measured by average graduation rates and peer quality; they were about 3.7 percentage points more likely to graduate from a four-year college in Texas, and were 3.9 percentage points more likely to graduate from UT Austin. Pulled-in students also enjoyed higher earnings 9 to 11 years after high school graduation. The researchers conclude that their results “are…consistent with well-prepared students from poorer high schools benefiting from attending higher quality colleges.”

Among pushed-out students, the TTP change resulted in a 3.7 percentage point decline in the likelihood of attending UT Austin and an increased likelihood of attending another four-year school or community college in Texas. The policy did not lead to significant changes in overall college enrollment rates for these students, although they attended less selective schools as a result of the TTP rule. This did not appear to significantly reduce either four-year college graduation rates or earnings nearly a decade after graduation for these students.

The researchers conclude that their “results are consistent with college selectivity mattering for students from disadvantaged schools but not mattering for students from more advantaged schools…These different effects may be driven by peers, mentors, or parents who can help insulate students displaced from selective institutions.”

— Dwyer Gunn