Married Women Who Retire Early May Forfeit Social Security Wealth

Women tend to marry men who are older and to retire at the same time as their husbands. This pattern contributes to a substantial gender gap in Social Security wealth.

Health status, expected Social Security benefits, and the leisure associated with reduced work are among the considerations that affect the retirement decisions of married couples. Because women live longer, on average, than men, and often have interrupted careers as a result of childbearing, one might expect them to retire later than men. In The Return to Work and Women's Employment Decisions (NBER Working Paper No. 24429), Nicole Maestas examines retirement patterns of couples. She documents two patterns: women tend to marry older men and couples often retire at the same time. She then shows that by retiring early, women often forego both substantial future earnings and significant amounts of prospective Social Security benefits that they would have received if they had worked longer.

Using the Health and Retirement Study, Maestas compares two groups over time: the "early cohort," born from 1936 to 1947, and the "boomer cohort," born from 1948 to 1959. The oldest members of the early cohort reached age 62 in 1998; the oldest members of the boomer cohort turned 62 in 2010. In the early cohort, 69 percent of women are younger than their husbands, by an average of 2.7 years. For the boomer cohort, 63 percent of wives are younger, with an average age difference of 2.0 years.

The average employment rate, lifetime number of years worked, annual earnings, and hourly wages all increased from the early cohort to the boomer cohort for women ages 51 to 56. For men in their early 50s, the employment rate and the number of years worked both declined; earnings and hourly wages grew, but less so relative to women. Maestas finds that the employment rate for married women was higher at every age from 51 to 64 for the boomer cohort relative to the early cohort. In contrast, the employment rate for men in the boomer cohort was lower than the early cohort until age 58.

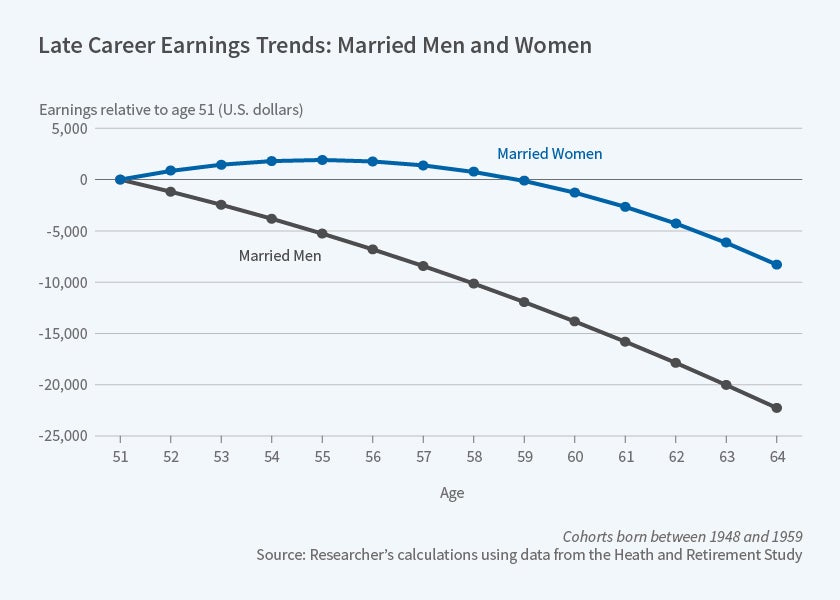

For both female cohorts, real earnings increased until age 55 and began to decline at age 57. Men's earnings, on the other hand, continuously decreased from ages 51 to 61. In addition, women's earnings increased by 31 percent across cohorts, but men's earnings increased only 10 percent. So the gender earnings gap shrinks as individuals age into retirement.

For both cohorts, women were more likely than men to retire "early" — before age 62 — or move from full- to part-time employment. In the boomer cohort, 47 percent of women retired or reduced work early, but only 41 percent of men did so.

Social Security benefits at age 65 — determined by an individual's highest annual earnings over a 35-year period — are higher for women in the boomer cohort. For example, average Social Security wealth (SSW), the present discounted value of lifetime benefits, for women in the boomer cohort is about $145,000, 26 percent greater than the average value for the early cohort. Men's SSW also increases across cohorts, but only by 7 percent. Maestas calculates that SSW would be substantially higher for women in both cohort groups if they continued working until age 70: 17 percent higher for early cohort women and 10 percent higher for the boomer cohort. Conversely, SSW for men would decline by 3 percent (in real terms) in the early cohort and by 1 percent in the boomer cohort if they worked until age 70. This is because women's earnings later in life replace lower earnings years from earlier in a woman's career — men see no such benefit. If women continued to work through their 60s, this would virtually eliminate the gender gap in SSW.

When ranked by the amount of additional SSW they would receive if they worked to age 70, married women in the top quartile would gain an average of over $36,000, compared with only $1,300 for those in the bottom quartile. Despite these potentially significant differences in the financial consequences of early retirement, Maestas finds that the early retirement rate among women with a lot to gain from continued work is comparable to that for women with relatively little potential gain. "This suggests that individuals do not factor these potential gains into their employment decisions, and it raises the question of whether individuals are able to correctly assess the opportunity costs associated with reducing work effort before age 70."

— Morgan Foy