Economic and Financial Consequences of Corporate Cyberattacks

After suffering a breach of customers' personal data, the average attacked firm loses 1.1 percent of its market value and experiences a 3.2 percentage point drop in its year-on-year sales growth rate.

In late 2017, a cyberattack exposed personal information on nearly 70 million customers of Target Corp., the Minnesota-based discount retailer. Customers worried about the potential cost of stolen phone numbers and credit card information. The combination of reduced customer traffic, costs associated with responding to the breach, and the need to establish reserves against future legal judgements reduced Target's earnings before interest and taxes by nearly 30 percent — a reduction of the company's earnings by $1.58 billion, from $5.52 billion for the year before the attack to $3.94 billion for the year after it. Costs directly related to the attack, including settlements of lawsuits, totaled $292 million.

In What is the Impact of Successful Cyberattacks on Target Firms? (NBER Working Paper No. 24409), Shinichi Kamiya, Jun-Koo Kang, Jungmin Kim, Andreas Milidonis, and René M. Stulz identify characteristics of companies most likely to fall victim to cyberattacks and assess the financial and economic consequences. They study cyberattacks on public corporations reported to the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse over the 2005-14 period. The most likely victims are firms that are high-value and have a high profile. They also tend to have more intangible assets on their balance sheets and to have boards which have historically been less attuned to risk. Attacks that breach customers' personal financial data do the most damage, eroding equity value, undermining credit ratings, and frightening away customers.

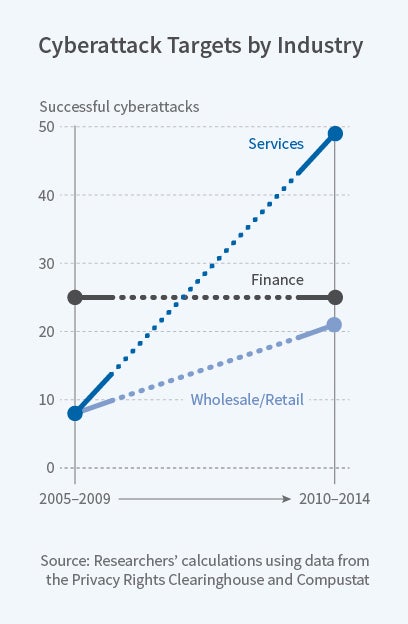

Of the 188 cyberattacks in the study sample, 30 percent were in the service industry, 27 percent in finance, 18 percent in manufacturing, and 15 percent in wholesale and retail trade. When firms suffered breaches of personal data, such as Social Security numbers and bank information, the average immediate loss in stock value was 1.12 percent, or $607 million, based on a mean market value of equity of $54.2 billion. Firms that experienced repeated attacks and/or lacked explicit risk monitoring committees suffered significantly greater losses.

Sales growth for large firms declined by 3.4 percentage points following an attack, relative to before the attack. Compromised companies in the retail sector experienced a 5.4 percentage point decline in sales growth.

Attacks can have long-run effects. Credit ratings of the victims of corporate cyberattacks remain depressed for three years. Further, the firms endure heightened cash flow volatility and report a lower ratio of net worth to total assets, reflecting less capacity to weather adversity.

Compared with non-affected firms, those hit by cyberattacks are more likely to raise money by borrowing than by issuing stock. When they borrow, they do so at longer maturities, to reduce their exposure to rollover risk.

Firms respond to cyberattacks by increasing their attention to cybersecurity. In many cases, the board of directors explicitly prioritizes risk management or establishes a risk oversight committee. Firms also appear to adjust CEO compensation policies to reduce CEOs' risk exposure and risk appetite. In the three years after an attack, the average CEO sees stock option awards decline by 6.6 percent, while restricted stock grants — which are more subject to downside risk — increased by 10.4 percent. CEO turnover was not significantly higher at firms that experienced a successful attack than at non-affected firms.

— Steve Maas