The Long-Run Effects of Immigration during the Age of Mass Migration

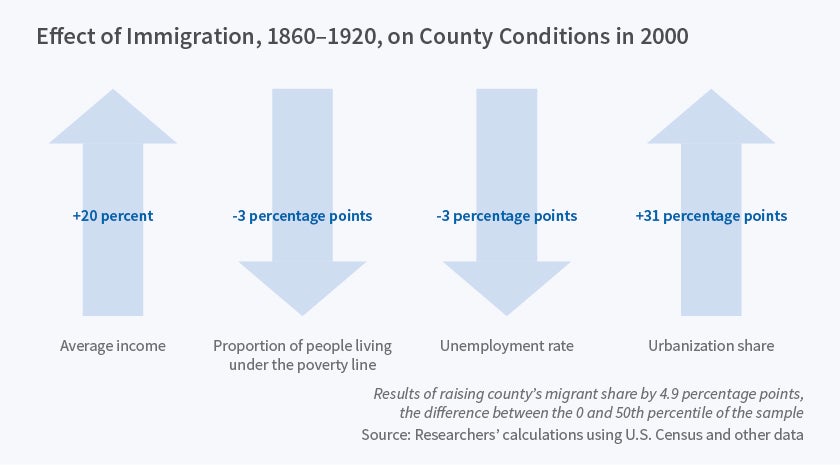

U.S. counties that received larger numbers of immigrants between 1860 and 1920 had higher average incomes and lower unemployment and poverty rates in 2000.

Studying immigrant flows during the period of highest immigration in U.S. history, Sandra Sequeira, Nathan Nunn, and Nancy Qian find that counties that received large influxes of immigrants experienced both short- and long-term economic benefits compared with other regions. In Migrants and the Making of America: The Short- and Long-Run Effects of Immigration during the Age of Mass Migration (NBER Working Paper 23289), they report that these benefits were realized without loss of social and civic cohesion and the long-term benefits persisted to the dawn of the 21st century.

The researchers recognize that immigrants may have been drawn to locations with particular attributes, and that these attributes may also have contributed to those locations' subsequent growth. They therefore focus on differences in the dates on which counties became connected to the railway network, which made it much easier for immigrants to reach a particular location, as a source of quasi-random variation in immigrant inflows.

Using census data along with historical railway maps and other source information, the researchers track county-level immigration, along with the decade-by-decade fluctuations in immigrant flows to the United States. The gradual expansion of railway networks, which connected only 20 percent of the nation in 1850 but 90 percent by 1920, together with the timing of waves of immigration, provide variation in how accessible different locations were to immigrants from 1850 to 1920.

A central finding is that the economic benefits of immigration were significant and long-lasting: In 2000, average incomes were 20 percent higher in counties with median immigrant inflows relative to counties with no immigrant inflows, the proportion of people living in poverty was 3 percentage points lower, the unemployment rate was 3 percentage points lower, the urbanization rate was 31 percentage points higher, and education attainment was higher as well. The researchers do not find any cost of immigration in terms of social cohesion. Counties with more immigrant settlement during the Age of Mass Migration today have levels of social capital, civic participation, and crime that are similar to those of regions that received fewer immigrants.

Measuring the short-term impacts of immigration from 1850 to 1920, the researchers find a 57 percent average increase by 1930 in manufacturing output per capita and a 39 to 58 percent increase in agricultural farm values in places that received the median number of immigrants relative to those that received none. Though some of the counties studied show a lower rate of literacy due to the influx of immigrants, many of whom did not speak English, the researchers find that illiteracy declined steadily over the years and that there was an increase in innovation activity, as measured by patents per capita, in counties with large immigrant populations.

The long-run positive effects of immigration in counties connected to rail lines appear to have arisen from the persistence of the short-run benefits, particularly greater industrialization, agricultural productivity, and innovation.

"Taken as a whole, our estimates provide evidence consistent with a historical narrative that is commonly told of how immigration facilitated economic growth," the researchers conclude. "Despite the unique conditions under which the largest episode of immigration in U.S. history took place, our estimates of the long-run effects of immigration may still be relevant for assessing the long-run effects of immigrants today."

— Jay Fitzgerald