Tax Haven Financing Skews Cross-Border Investment Statistics

In 2017, securities issued by corporations based in tax havens — mostly offshore financial centers — accounted for 10 percent of the value of outstanding corporate bonds worldwide and about 8 percent of global equity.

Official statistics on foreign investment show that investors from the United States, the eurozone, and other large developed nations invest relatively little in large, fast-growing, emerging markets. These statistics are misleading, according to the findings presented in Redrawing the Map of Global Capital Flows: The Role of Cross-Border Financing and Tax Havens (NBER Working Paper 26855), because they don’t take into account the holdings of securities issued in tax havens, many of which represent claims on emerging market firms.

In 2017, for example, these data indicated that US investors held $144 billion in Australian corporate bonds, compared to only $8 billion in Brazil and $3 billion in China. When the researchers link securities to the countries of their ultimate issuers, US investors hold $50 billion in Brazilian corporate bonds and $47 billion in Chinese bonds. When stock holdings are added, the total of US investments in China soars from the official $160 billion to roughly $750 billion. This pattern is common to many other large investor economies.

Adjusting for the effect of investment companies based in tax havens gives a better picture of the size of global financial imbalances, the currency risk of a nation’s external liabilities, and the rise of the globalization of finance, according to the researchers Antonio Coppola, Matteo Maggiori, Brent Neiman, and Jesse Schreger.

Tax havens are mostly small nations, like the Cayman Islands and Bermuda, and their tax rules tend to attract many shell companies. In 2017, securities issued in these countries accounted for 10 percent of the total value of holdings of corporate bonds worldwide and about 8 percent of global equities. The researchers use data from seven commercially available sources to link investments in tax haven based entities to the countries of their beneficial owners.

The investments take various forms. For example, Brazil’s Vale SA, a mining and logistics company, has a subsidiary in the Cayman Islands called Vale Overseas Ltd. Thus, official data lists the Caymans as the location of the investment, when in actuality the subsidiary simply issues bonds. The researchers reallocate these bonds and treat them as Brazilian.

The study also reallocates holdings and liabilities of foreign affiliates in nations besides the tax havens. For example, the securities of Toyota Motor North America — officially US securities — can be adjusted to become Japanese securities.

The reallocations can expose patterns in the data that the official data obscure. One example is US investment in Brazilian bonds. The US Treasury’s International Capital data show that only 25 percent of such investments are in corporate bonds, while the researchers’ adjustments raise the percentage to 66 percent. The adjustments also reveal that a larger share of developed market investment in emerging markets bonds is in foreign currency than the official data suggest.

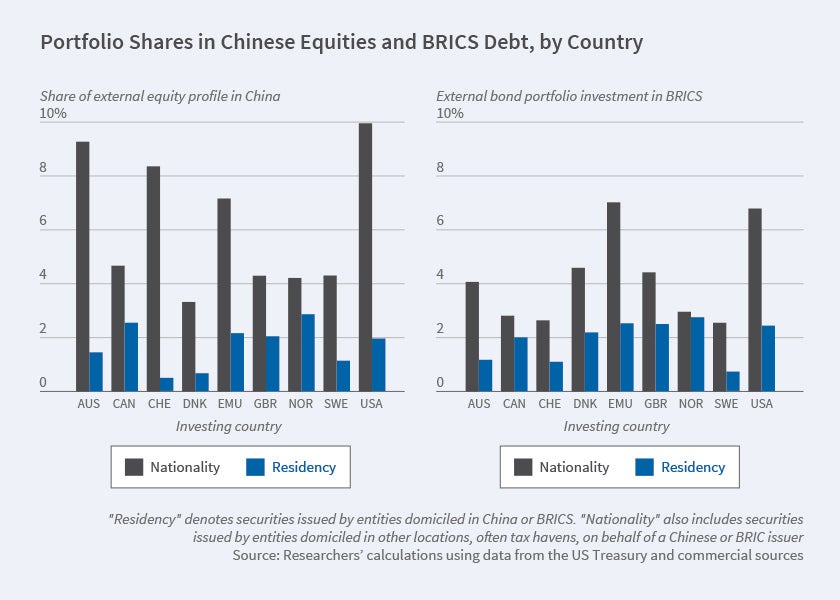

The researchers find that the nation with the largest reallocation is China. Big Chinese firms, such as Alibaba, Baidu, JD.com, and Tencent, have adopted a unique corporate structure known as a variable interest entity (VIE) as a result of restrictions on foreign ownership in strategic industries. While foreign investors own equity claims on the tax haven-based shell companies, the equity of the operating firms located in China needs to remain in the hands of Chinese citizens to satisfy Chinese regulations. These positions are very large; the researchers estimate that nearly 10 percent of US and eurozone foreign equity positions actually represent claims on Chinese firms, rather than the 2 percent in the official data.

The stock market valuation of these Chinese tech giants has soared in recent years, but these valuation effects are not reflected in China’s official external accounts due to the use of the VIE offshore structure. The researchers calculate that this leads China’s official net foreign asset position to be overstated by more than $1 trillion. Adjusting for offshore VIE structures, China appears to be a much smaller net creditor to the rest of the world than it is in the official data.

—Laurent Belsie