High-Speed Rail Expansion and German Worker Mobility

Expansion of the network between larger and smaller cities reduced travel times by 13 minutes on average, and increased the number of commuters working in smaller cities while retaining homes in larger ones.

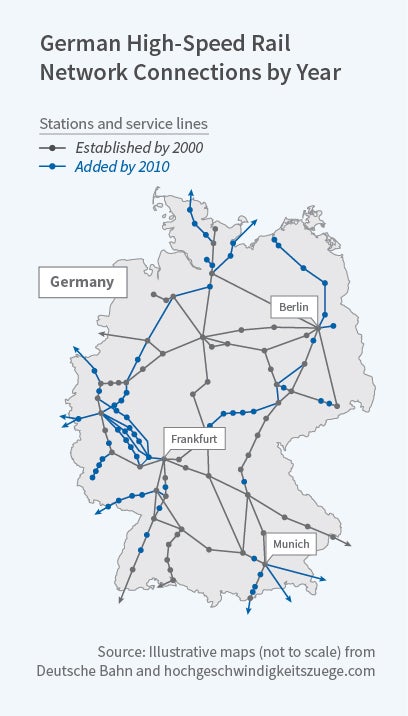

Starting in the late 1990s, Germany expanded its high-speed rail network (HSR), connecting outlying locales to large urban areas. In The Effect of Infrastructure on Worker Mobility: Evidence from High-Speed Rail Expansion in Germany (NBER Working Paper No. 24507), Daniel F. Heuermann and Johannes F. Schmieder study how this large-scale infrastructure investment affected commuter behavior. They find that the expansion reduced travel times and increased commuting, as workers moved to jobs in smaller cities while keeping their places of residence in larger urban areas.

Until the late 1990s, the HSR system connected the largest cities of Germany. The connected cities were located in just three of the 16 German states. Areas between the large cities, through which the tracks ran, campaigned for stations, and in a second wave of expansion, the government added stops in many of these cities.

The researchers analyze the effects of this infrastructure improvement by comparing cities granted stops in the second wave of expansion with other small German cities that were not added to the rail network. They note that new rail stops were not placed due to economic conditions, such as connectedness to urban centers, but because of political factors. Moreover, unlike infrastructure investments in roads and highways, the HSR system exclusively carries passengers. It does not transport goods, so it affects labor but not product markets.

The researchers create a dataset that includes travel times, train schedules, and administrative employment data, which contain the region of work and residence for each traveler.

For the average pair of cities in their study, the high-speed rail expansion reduced travel time by 13 minutes, or about 10 percent of the pre-expansion time. The number of commuters rose by 0.25 percent for each 1 percent decrease in travel time. Reductions in commuter time and the corresponding increase in passengers followed an inverted U-shaped pattern, with the largest impacts occurring on routes of 200 to 500 kilometers in length.

The researchers estimate that 840,000 people started to use rail transportation for commuting during their 1994-2010 sample period. Twelve percent of the increase in ridership was attributable to the 10 percent reduction in commuting time as a result of HSR expansion.

The researchers find that the number of commuters from small cities to large cities is 40 percent larger than the number commuting from large to small cities. The opposite pattern, however, commuting from large cities to small, was much more sensitive to the reduction in travel time from HSR expansion. This supports the view that workers enjoy living in large urban areas and are not there solely for employment.

The study concludes that the gains from the investment in infrastructure accrued mainly to smaller cities. Commuters are twice as likely as non-commuters to be college graduates, which suggests that building HSR networks may be one way to engage relatively high-skilled workers in the economies of peripheral regions.

— Morgan Foy