Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom

Large down-payments and sharp recent increases in household income mean the housing frenzy in China is unlikely to trigger a national financial crisis.

China's housing-price appreciation from 2003-13 has been enormous—stronger than during the recent U.S. housing bubble and more on the order of Japan's property boom in the 1980s, according to Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom (NBER Working Paper No. 21112). Would a drop in house prices wreak havoc on China's financial markets and its economy more generally? A number of factors suggest that the risk of a price decline is modest and that the effects of a decline would be muted, according to researchers Hanming Fang, Quanlin Gu, Wei Xiong, and Li-An Zhou.

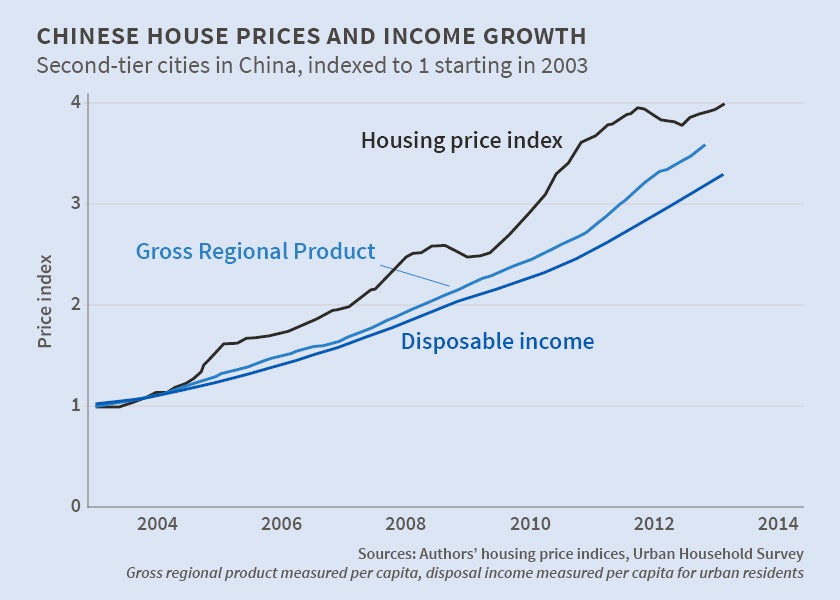

One key factor is that the rise in Chinese housing values has been accompanied by an equally strong rise in household income. Another is that even though those at the lower rungs of the income chain are buying homes that are worth eight, sometimes 10, times their annual disposable income, the Chinese have shown remarkable resilience in holding onto their property. One reason is that buyers in China typically put down more than 35 percent on a home, which reduces their mortgage payments and insulates the buyers and the banks that lend to them from a plunge in property values.

"[T]he housing market is unlikely to trigger an imminent financial crisis in China, even though it may crash with a sudden stop in the Chinese economy and act as an amplifier of the initial shock," the authors conclude.

By studying comprehensive mortgage data from a major Chinese commercial bank, the authors constructed a set of housing price indices for 120 major cities in China. Since many Chinese buildings are new, there are not yet many resales of units. The researchers therefore measured the price rise over time by comparing similar housing units within the same development. They found that in first-tier cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen—housing prices rose by an annual average real rate of 13.1 percent between 2003 and 2013. In second-tier cities, annual real appreciation was 10.5 percent; in third-tier cities, 7.9 percent.

A key difference between the Chinese house price run-up of the last decade, and the U.S. house price bubble of the early 2000s and the Japanese house price increase of the 1980s, is that Chinese incomes have grown sharply as prices have risen. The authors calculate that during the period studied household income grew at an average annual real rate of 9.0 percent in China, except in the first-tier cities, where the growth was closer to 6.6 percent a year.

"The enormous income growth rate across Chinese cities thus provides some assurance to the housing boom and, together with the aforementioned high mortgage down payment ratios, renders the housing market an unlikely trigger for an imminent financial crisis in China," they write.

Still, there are risks. Chinese home-buyers, especially those whose incomes fall in the bottom 10 percent of homeowners, take on extreme financial burdens to buy homes. They pay up to 10 times their annual disposable income to buy a property. These households—typically near the 25th percentile of the overall income distribution—have to save about three years of their household income to accumulate a down payment. Even with a generous down payment, say 40 percent, which reduces the monthly loan payment, and a relatively low 6 percent mortgage interest rate, such households will still need to devote 45 percent of their disposable income to servicing the loan.

Households can make that work as long as income continues its rapid growth, but there are signs that China's economy is slowing. The authors caution that if China's growth rate does decline, and especially if the economy experiences a sudden stop with a dramatic decline in growth, then house prices could decline. Even if this did not destabilize the financial system, they warn, the decline could amplify the initial shock to economic activity.

— Laurent Belsie