Income Mobility in the Families of Immigrants and US Natives

Sons of immigrant fathers experience more income growth than sons of US-born fathers, in large part because immigrants choose to settle where children have good prospects.

Analyzing waves of immigrants to the United States between 1880 and 2015, Ran Abramitzky, Leah Platt Boustan, Elisa Jácome, and Santiago Pérez find that sons of first-generation immigrants have greater upward income mobility rates than sons of US-born parents. This mobility gap is observed throughout more than 100 years of data and does not vary significantly over time, despite extreme changes in the immigrants’ countries of origin and in US immigration policies.

In Intergenerational Mobility of Immigrants in the US over Two Centuries (NBER Working Paper 26408), the researchers identify three cohorts of first-generation immigrants and US-born workers. The first two cohorts, totaling 4 million father-son pairings, were taken from the 1880 and 1910 censuses, which provided each person’s name, year of birth, and place of birth. These cohorts and their sons were followed 30 years later, in the 1910 and 1940 censuses, respectively. (Daughters’ records were difficult to trace due to name changes upon marriage and are not included in this study.) In the 1940 census, income data were reported; for the earlier census records, income data for each individual were imputed using other available information, such as occupation. The first cohort of immigrants, those observed in the 1880 census, arrived primarily from countries in northern and western Europe while the 1910 cohort includes more immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

The third cohort was identified using administrative data on the income of 2.7 million father-son pairs provided by the Opportunity Insights project, as well as the General Social Survey, which includes occupational data. These immigrants arrived primarily from Latin America and Asia, and the researchers observe the children in the contemporary labor market.

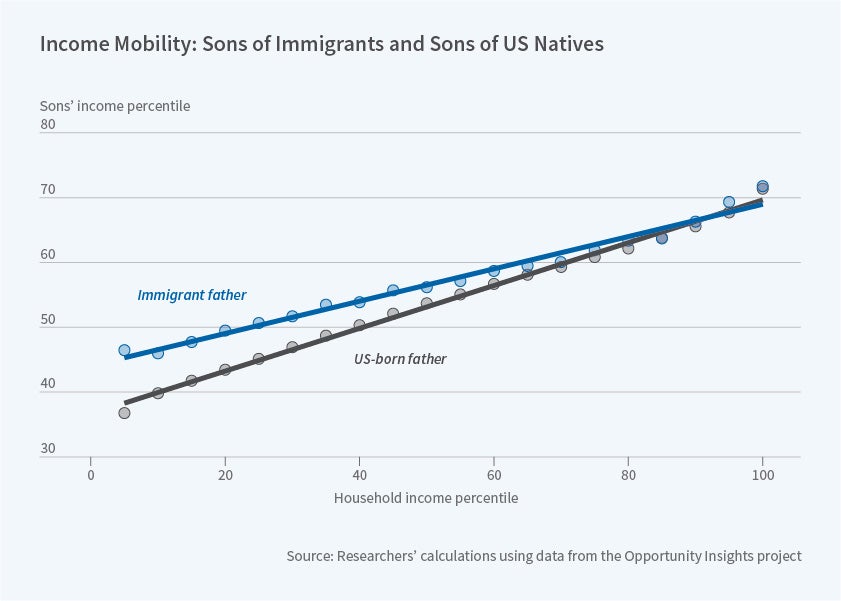

Across all three cohorts, sons of immigrants at the low end of the income distribution were more likely to experience an upward movement of their income levels, relative to their fathers, than sons of US-born workers. (The same is true for the daughters of immigrants, who can be studied in the modern data.) For example, among children with parents in the 25th percentile of the income distribution of the three cohorts, second-generation immigrants on average achieved a ranking 3 to 6 percentile points higher in the income distribution than children of US-born workers. This income mobility gap was smaller at the 75th percentile of the distribution and shrank over time. In the earlier cohorts, the second-generation immigrants gained 2 to 5 percentile points more than US-born workers, and in the most recent third cohort, this advantage fell to less than 2 percentile points.

One of the primary factors contributing to this gap seems to be that after arriving in the US immigrants have located in places where children have higher mobility prospects. The income mobility gap between children of immigrants and those of US-born workers diminishes by almost 70 percent when children’s income levels are compared within a geographic region. When the researchers examined mobility data at the county level, the gap disappeared: the sons of immigrants and the sons of US-born workers earned the same when they grew up in the same county and the economic strength of the specific geographic region led to better or worse benefits for all.

Differences in education between the children of immigrants and of US-born parents do not explain the income mobility gap in the historical cohorts. Across comparable families, immigrant children did not attain more education than the children of US-born workers.

The age at which a father arrived in the United States was related to upward mobility. The highest rates of upward income mobility occurred for children of fathers who arrived as adults, particularly when the fathers came from non-English-speaking countries. This could indicate that adult immigrant fathers’ rank in the US income distribution did not necessarily reflect their true earnings potential, and that fathers who arrived as children had greater opportunities to acquire US-specific skills.

— Jennifer Roche