Behavioral Changes Triggered by Information about Pollution

In China, an air-quality monitoring and disclosure program focused on fine particulate matter pollution led residents to buy air purifiers and to delay going out when pollution was high.

Although China has long had some of the most polluted cities in the world, few Chinese residents had access to accurate information about pollution levels. Then, in 2013, the country rolled out an air-quality monitoring and disclosure program, providing residents with real-time air pollution information from over 1,400 monitoring stations throughout the country. In From Fog to Smog: The Value of Pollution Information (NBER Working Paper 26541), Panle Jia Barwick, Shanjun Li, Liguo Lin, and Eric Zou find that the program has dramatically increased households’ awareness of pollution issues, and that this has triggered a range of behavioral changes to mitigate the health impacts of pollution.

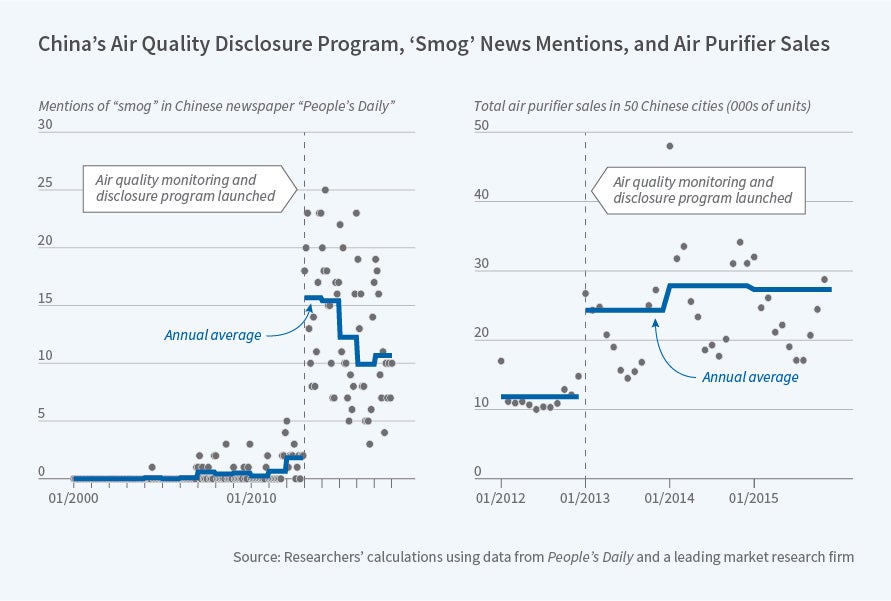

Prior to the advent of the program, accurate information about pollution levels and consumer awareness of pollution impacts were limited. The researchers first confirmed that the program, which was rolled out in a staggered manner across three groups of cities over two years, successfully increased awareness of pollution levels. The program resulted in a noticeable increase in articles about air pollution in the government’s official newspaper, People’s Daily, as well as a surge in the number of mobile phone apps providing users with air pollution data. The word “smog” also became more prevalent on social media platforms. Web searches for information about pollution skyrocketed, and purchases of air purifiers doubled within a year of program implementation in areas where the program was rolled out.

The researchers next explored how households changed their behavior in response to the new information about pollution. Using data on credit- and debit-card transactions, they found that the program increased pollution-avoiding behaviors, particularly in consumption categories that are comparatively flexible and easy to delay, such as trips to the supermarket or meals outside the home.

Information about local pollution levels also affected housing prices. While prior to the program the study found no correlation in the Beijing market between housing prices and proximity to polluters, an increase in pollution of one standard deviation reduced housing prices there by between 4 and 6 percent after the program. The price effects were particularly noticeable for houses located near the biggest polluters: houses within three kilometers of a major polluter were found to be 27 percent less valuable (relative to those that were 10 kilometers away) after pollution data were available.

The behavioral modifications that Chinese households made in response to the pollution information had meaningful health effects. The researchers estimate that access to pollution information reduced premature deaths attributable to air pollution exposure by nearly 7 percent. The mortality declines were concentrated among cardiorespiratory cases and were larger in areas that were more urban, had more hospitals, and used more electricity and mobile phones. In economic terms, the program delivered between Chinese ¥130 and ¥520 billion (US$18.6 to $74.6 billion) of benefits. These benefits outweighed the costs of the program and associated avoidance behaviors combined.

The researchers conclude that their findings “highlight the considerable benefits of collecting and disseminating pollution information in developing countries, many of which are experiencing the worst mortality damage from pollution exposure in the world.”

— Dwyer Gunn