Does Creative Destruction Really Drive Economic Growth?

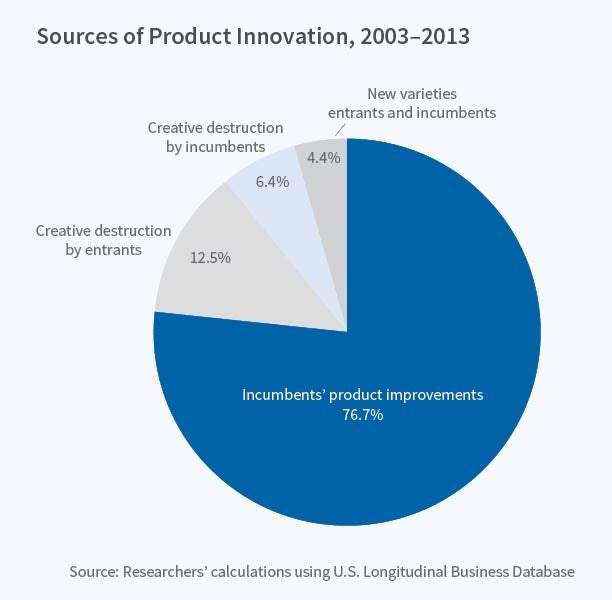

Incumbent firms' improvements on their own products appear to be more important than creative destruction by innovative startups as sources of growth.

Creative destruction is often seen as the primary engine of growth in the modern economy. Upstart businesses generate profits and jobs, the theory suggests, by introducing new goods that displace existing products or by devising innovative ways to improve on the products of competing firms.

That view of progress is challenged in How Destructive Is Innovation? (NBER Working Paper 22953). Researchers Daniel Garcia-Macia, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Peter J. Klenow argue that, while creative destruction plays a vital role in driving economic growth, it is not the dominant force. They find that creative destruction only accounts for about 25 percent of growth, with most of the remainder coming from refinements that established firms make to their own products.

The study examines patterns of job creation and job destruction among private sector firms in the American nonfarm economy, using the U.S. Longitudinal Business Database (LBD) from 1976-86 and 2003-13. The analysis focuses on employment shifts that are a by-product of innovation, which, in contrast to earlier work that focused on patents in the manufacturing sector, allows the researchers to study the entire nonfarm private sector.

The researchers assume that new firms—companies less than five years old—initially offer a single product which they obtain by improving upon an existing product or creating a new variety, while established firms potentially accumulate and produce multiple varieties. They note that the various types of innovation are all sources of growth and attempt "to illustrate how they might leave different telltale signs in the microdata."

The researchers argue that the role of entrants should be tied to the employment share of young firms. Creative destruction should show up as large employment declines (and, in the extreme, exit) among some incumbents and major growth among those doing the destroying: it should show up in the tails of the distribution of employment changes across firms. In contrast, when incumbents improve their own products, there should be much smaller changes in firm employment. Think of a retailer upgrading an outlet as opposed to opening a new store and driving out a competitor. Incremental innovations within firms are likely to show up as employment changes in the middle of the job growth distribution—precisely where many changes are found.

While creative destruction is vital for explaining extreme employment declines and exit, most employment changes, even over five-year periods, are much more modest. The researchers therefore conclude that most innovation takes the form of incumbents improving their own products. They show that the relative contributions to growth by new entrants to the market declined from 1976-86 to 2003-13, as did all growth attributable to creative destruction. But the growth contributions of existing firms—particularly through improving their own goods—rose. Most growth seems to occur as a result of quality improvements rather than the development of new varieties.

Between 1976 and 1986, about 27 percent of growth could be attributed to creative destruction, well below the 65 percent that resulted from improvements established companies made to their existing products. The remaining 8 percent was from the generation of new varieties of existing products.

From 2003 to 2013, creative destruction accounted for 19 percent of growth, compared with 77 percent from product improvements by existing firms. New varieties of products accounted for 4 percent of growth in this period.

Only a modest proportion of job growth comes from new firms, which supports the researchers' conclusion that most growth comes from established firms rather than new entrants. The employment share of new firms averaged 22 percent during the period 1976-86, but was 7 percentage points lower, 15 percent, during 2003-13. The job creation rate in total fell by 12 percentage points between those two periods. More than half of that decline was due to the drop in the employment share of the new firms, reflecting less innovation by them.

—John Laidler