Dynamic Complementarity in Head Start and K-12 Classes

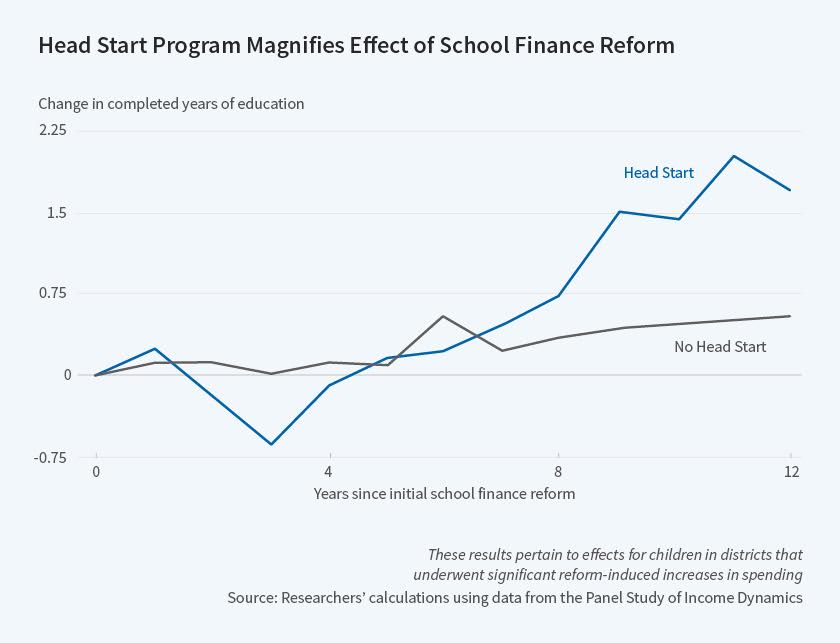

The effects of increases in Head Start spending on academic outcomes were larger when participants in the program subsequently attended schools that were comparatively well-funded as a result of court-ordered reforms.

In Reducing Inequality Through Dynamic Complementarity: Evidence from Head Start and Public School Spending (NBER Working Paper No. 23489), Rucker C. Johnson and C. Kirabo Jackson find synergistic benefits from increased investment in Head Start and increased investment in K-12 education. While spending of either type improved academic outcomes to some degree, access to both resulted in a dynamic complementarity that offered far greater long term benefit.

Launched in 1964 as one of President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty programs, Head Start aims to enhance literacy, numeracy, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making skills. Funding of local programs comes primarily through grants from the federal government, with local grantees expected to provide about 20 percent of the funding. Children must be four years old to be eligible to participate, and at least 90 percent of children in each Head Start center must come from families with incomes below the poverty line.

Funding increases in public schools examined in this study are the result of court-ordered school finance reforms (SFRs) launched between 1971 and 2010 to correct some of the inequities between school systems due to the varying wealth of districts. By focusing on SFRs, the researchers were able to identify spending increases that were arguably unrelated to other confounding influences on student outcomes. Data on annual Head Start spending was compiled at the county level, and public K-12 spending at the school district level.

Rather than relying on test scores to evaluate Head Start and K-12 spending, the researchers use the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to look at the life trajectories of individuals born between 1950 and 1976. They have information on outcomes through 2013. By using the range of birth years, they were able to differentiate between individuals who reached the age of four at a variety of Head Start spending levels. They use various strategies to control for the possible influences of family circumstances and other local policy changes unrelated to Head Start or K-12 spending levels.

The researchers find that the marginal effects of increases in Head Start spending are more than twice as large when students attend schools with K-12 spending at the 75th percentile rather than at the 25th percentile. In 75th percentile schools, exposure to Head Start raised later educational attainment by 0.22 years, adult wages increased by 5.6 percent, and the likelihood of adult incarceration fell by 2.2 percentage points. In comparison, educational attainment increased 0.096 years, wages increased only 1.9 percent, and the likelihood of incarceration was lowered by just 0.75 percentage points among those exposed to Head Start whose public schools were in the 25th percentile of spending. At the same time, a 10 percent increase in K-12 funding had only minor effects on educational attainment, adult wages, and incarceration when the students did not attend Head Start beforehand. The dynamic complementarity that the researchers find may explain the varying results of other studies on the impact of Head Start on student outcomes that have not controlled for school spending during the K-12 years.

— Jen Deaderick