Tuskegee, Trust in Doctors, and the Health of Black Men

Disclosure of the Tuskegee syphilis study in 1972 coincided with increases in medical mistrust and mortality among black males.

The "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro," conducted in the mid-20th century in Macon County, Alabama, is one of the most infamous medical experiments in American history. Conductors of the study allowed hundreds of unwitting black men to suffer needlessly for decades and sometimes die in agony, despite the availability of proven and effective medical treatments.

In Tuskegee and the Health of Black Men (NBER Working Paper 22323), Marcella Alsan and Marianne Wanamaker find evidence that the suffering associated with this experiment extended far beyond the tragic test subjects. They find that public revelations in 1972 of the study's existence led to a deep mistrust of the medical community among black males, many of whom afterward shunned hospital and physician interactions. The researchers estimate that life expectancy at 45 for black men fell sharply and that the life expectancy gap between black and white males significantly widened.

Over the years, numerous studies have shown that the health of American black males is significantly worse than that of men in other ethnic, racial and demographic groups. African-American men have shorter life expectancy than white males and higher death rates from conditions such as cancer and heart disease. Previous studies have attributed these disparities to various factors, including poverty, inferior education, higher unemployment and underemployment, and lack of health insurance. Some have also suggested that mistrust of the medical system was a factor, but the existence and long-term effect of that mistrust has not previously been tracked or quantified.

The federally funded Tuskegee study followed the lives of about 600 largely poor black males, the majority of whom had syphilis, from 1932 to 1972. The goal was to trace the course of untreated syphilis. Researchers never told the test subjects the true aim of the study, asserting instead that they were helping the men and telling some they had been diagnosed with "bad blood." Medical researchers not only deliberately withheld from the men proven treatments, such as penicillin, but also actively discouraged the test subjects from seeking medical advice elsewhere. In exchange for hot meals and promises to pay for their burial expenses, for 40 years the subjects allowed the study's principals to examine them, draw blood, conduct spinal taps, and ultimately to perform autopsies.

In 1972, the study came to an abrupt halt after its disclosure by news media sparked public shock and outrage. The sudden stop created a distinct before-and-after point around which the researchers could compile and compare historical data regarding medical trust, treatments, and results. Their data on medical trust are drawn from the General Social Survey, while medical behavioral data come from the National Health Interview Survey. They also obtained annual mortality data by race, gender, age group, and causes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

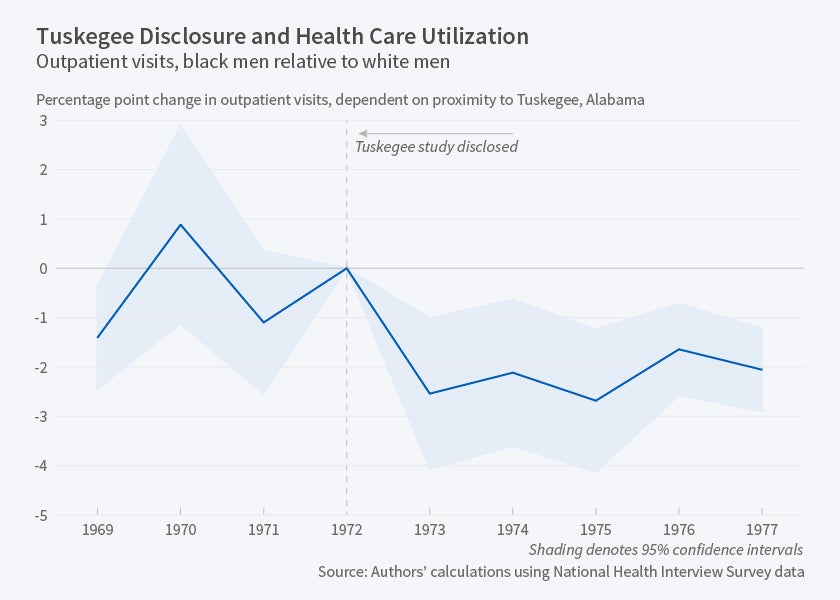

Focusing on black males between the ages of 45 and 74, the researchers describe changes in racial mortality and health care utilization gaps after 1972. Their main finding is that the disclosure of the syphilis study was associated with a sharpening of these racial differences along a continuous geographic gradient from Tuskegee, Alabama. In the years following disclosure of the study's tactics, they find significantly lower utilization of both outpatient and inpatient medical care by older black men in close geographic and cultural proximity to the study's subjects. The reduction in health care utilization paralleled a significant increase in the probability that such men would die before the age of 75. The researchers also document heightened medical mistrust, as measured in 1998, among black men in closer proximity to Tuskegee, Alabama.

The researchers estimate that life expectancy at age 45 for black men fell by up to 1.4 years in direct response to the 1972 disclosure of the Tuskegee study. This decline in longevity could explain approximately 35 percent of the 1980 life expectancy gap between black and white men. The disclosure of the Tuskegee project appears to have stalled, or even reversed, a pre-1972 trend toward narrowing of the racial health gap.

—Jay Fitzgerald