It’s the Quality of Sleep that Counts for Boosting Productivity

Productivity of workers in Chennai, India benefited less from increased sleep time at home, where sleeping conditions were poor, than from high-quality naps at their workplace.

Poor urban residents of developing nations sleep relatively little, and a new study from India suggests why. It’s not that they don’t spend enough time trying to sleep, but that the quality of the sleep they are getting is surprisingly poor.

Although participants in the study averaged eight hours in bed, they actually slept only 5.6 hours. They woke up 32 times per night. The frequent interruptions meant that their longest undisturbed sleep lasted only 55 minutes on the average night. Both total sleep time and longest undisturbed sleep are substantially lower than the averages for Americans, even for those with sleep disorders.

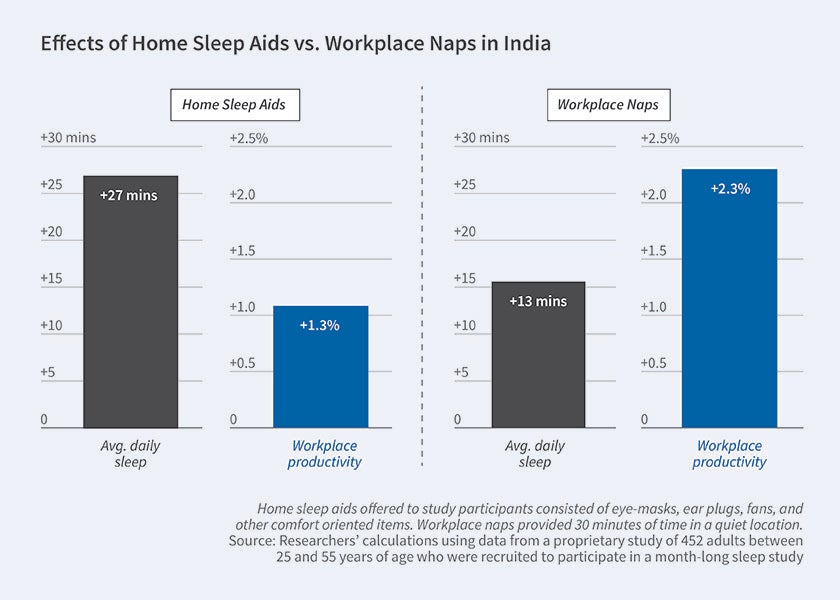

A three-week program that increased participants’ sleep time by 27 minutes per night did nothing to improve their productivity, cognition, psychological well-being, or patience. High-quality naps at the office, however, showed measurable improvements.

“These results suggest that high sleep quality may be essential to unlock the benefits of sleep,” Pedro Bessone, Gautam Rao, Frank Schilbach, Heather Schofield, and Mattie Toma write in The Economic Consequences of Increasing Sleep among the Urban Poor (NBER Working Paper 26746).

Even in rich countries, many people are not getting the seven to nine hours of sleep per night that experts recommend. In developing nations, the problem may be worse because noise, heat, mosquitoes, and other physical discomforts make it challenging for the urban poor to get the proper rest.

To measure sleep patterns, the researchers recruited 452 low-income residents of Chennai to work for a month doing data entry while wearing devices called actigraphs that track how much time their wearers are awake. Participants spent a week working and having their sleep monitored at all times. Then they were split into several groups. One group was encouraged verbally to spend more time sleeping. They were also given sleep aids, such as loaned eyeshades, ear plugs, mattresses, and fans. A subgroup was paid for each minute of extra sleep they logged.

The inducements were effective in increasing sleep time: these groups averaged an extra 27 minutes of sleep per night. But the quality of their sleep was poor. To achieve those extra minutes required an extra 38 minutes in bed, an overall sleep efficiency — time asleep divided by time in bed — of only 70 percent. In comparison, such a low number is found in the US only among individuals with severe sleep apnea or the elderly. Healthy people in the US have around 95 percent efficiency.

The net impact of increased sleep on productivity among those given inducements in the Chennai experiment was small: 1.3 percent. Rather than boosting their work time, the participants in this group cut back their work hours by 4 percent. That reduction in work and earnings negated any productivity increase.

Another group of study participants was encouraged to nap during a half hour of the work day in a quiet office space with beds, blankets, pillows, and the other items that the night-sleep group was given. The effects for this group were much more positive. This group averaged an added 13 minutes of sleep per day, and this higher-quality sleep boosted productivity by 2.3 percent. Tests also showed that participants demonstrated better attention, improved psychological well-being, increased savings, and more patience.

Members of the nap group earned 4.1 percent more than a control group of participants who were required to take a 30-minute break, but not a nap, during the work day. But they still ended up working 26 minutes less a day than a control group that was allowed to work during the half-hour nap time. That opportunity cost left their earnings 8.3 percent lower than those of the control group.

If it takes eight hours in bed to get less than six hours of poor-quality night sleep, and the productivity effects are small, workers may conclude that they are better off economically spending that time working. The high-quality naps show how gains might be made, but those conditions are unlikely to be replicated at home, the researchers conclude.

— Laurent Belsie