Sherman's March Left a Lasting Legacy of Retarded Development

As late as 1920, agricultural investment in Southern counties in the 10-mile-wide path of devastation lagged behind investment in counties that were spared.

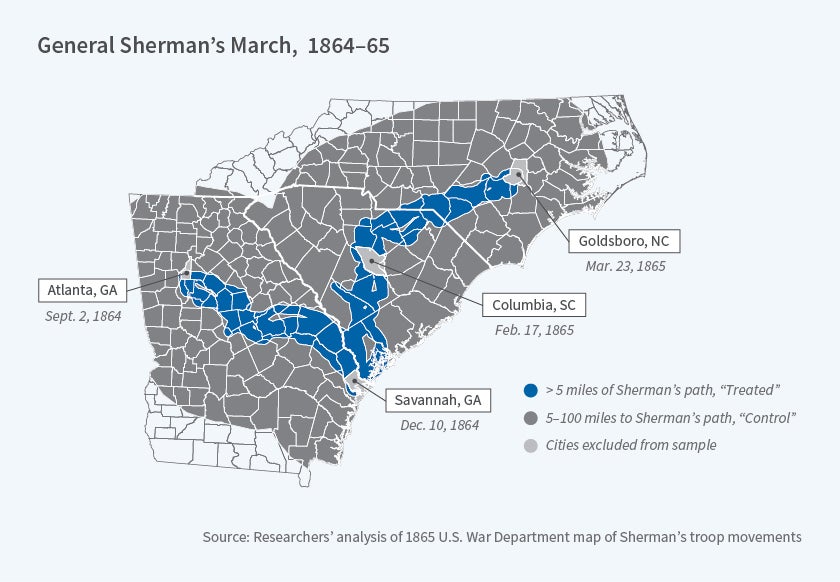

In the fall of 1864, General William Tecumseh Sherman wrought havoc on the economy of the Confederacy with his march to the sea through Georgia and the Carolinas.

Guided by census data, Sherman mapped out a 285-mile-long campaign with an eye toward demolishing the region's richest agricultural territory. Even a half-century later, the local economy still felt the effects of Sherman's scorched-earth tactics in a 10-mile-wide swath along the march's route.

In Capital Destruction and Economic Growth: The Effects of Sherman's March, 1850–1920 (NBER Working Paper 25392), James J. Feigenbaum, James Lee, and Filippo Mezzanotti explore the medium- and long-term impacts of the military campaign on agricultural investment, asset prices in the farm sector, and manufacturing activity. They study capital destruction and the obstacles to economic recovery, and find that the South's weak financial markets fell far short of meeting the challenges of postwar recovery, especially in the agricultural sector.

Using census data and other records, the researchers construct a control group of counties that were similar in 1860 to the counties in Sherman's path. In 1870, the value of farms in counties affected by Sherman's march declined 20 percent more than those in the control group. At the same time, the march caused a 14 percent decline in the acreage of improved land and value of livestock relative to control counties. As late as 1920, agricultural investment — proxied by improved land — continued to be lower in counties ravaged by the march than in those that were spared.

The researchers estimate similar declines in employment, capital, and manufacturing production in counties affected by the march. However, compared with agriculture, the impact on manufacturing was much less persistent. The manufacturing sector was relatively small in the pre-war South and expanded rapidly after 1870. This makes it difficult to determine statistically significant differences between march and non-march counties after 1870.

The war left the South with abundant investment opportunities but scant financial resources to exploit them. Before the war, the financial sector in the South was relatively underdeveloped. An 1859 financial register recorded that the Carolinas had only 2.9 banks for every 100,000 people; Georgia had 6.2; the national average was 7.1. By the end of the war, those three states had no banks.

The researchers observe that it is widely believed that banks provided little or no credit to small farmers before or after the war. Instead, these farmers obtained credit from local merchants, such as country stores, and from big landowners. Among the counties in Sherman's path, those with more country stores saw a smaller decline in agricultural activity and land investments than those with fewer merchants. Counties with a large share of affluent farmers also weathered the march better than others, but the concentration of land ownership also increased as cash-rich landowners bought property from cash-strapped farmers who had few credit options.

General Sherman's stated goal was to "make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war." The absence of a robust financial system, the researchers conclude, prolonged the pain for affected regions.

— Steve Maas