Who Benefits from Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education?

Researchers find that tax credits for higher education have little or no effect on college attendance; the credits are essentially transfer payments - and not primarily to the needy.

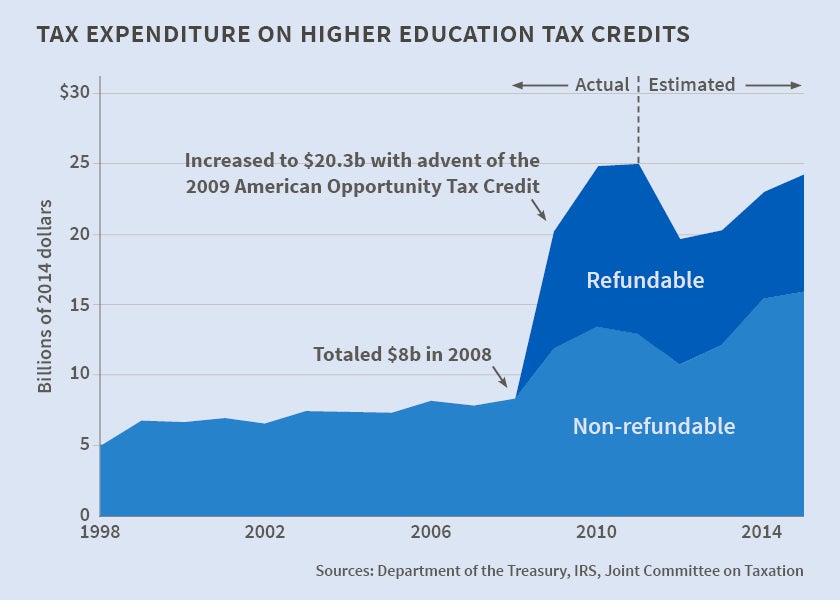

In 2014, the federal government spent about $23 billion on three programs offering tax credits to households paying for higher education. In The Returns to the Federal Tax Credits for Higher Education (NBER Working Paper No. 20833), George B. Bulman and Caroline M. Hoxby find that the credits have little or no effect on college-going in the U.S. The credits do not affect whether students enroll at all, whether they attend four-year colleges, how expensive their colleges are, or the scholarships and grants they receive. The authors conclude that the tax credits are primarily "a transfer from some individuals to others."

Tax credits for higher education began in 1997 with the Hope Tax Credit and the Tax Credit for Lifetime Learning. In 2009, the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) greatly expanded both the generosity of the credits and the number of eligible households.

The maximum AOTC is $2,500 per student for each of the first four years of postsecondary education. For each student, the household receives $2,000 for the first $2,000 spent and 25 percent of the next $2,000 spent. Because the AOTC is partially refundable, even a taxpayer who owes no taxes can receive up to $1,000 per student.

Before the AOTC, the tax credits for higher education mainly benefited middle-income households whose incomes were below $120,000 for married joint filers but whose children had a high probability of attending college for which their families paid. The AOTC raised the income threshold (to $180,000 for married joint filers) so that, now, the credits benefit upper-income households as well. Despite the fact that the AOTC is refundable, few of its benefits flow to low-income households because their children are less likely to attend college and, if they do attend, their families are less likely to pay. Instead, Pell and other grants cover much of their college cost.

The authors compare households whose incomes place them just below or above the income eligibility thresholds. Such households differ in eligibility but are otherwise extremely similar. The authors cannot detect any greater college-going among those who are eligible. The authors also investigate whether college-going increased after the introduction of the AOTC among households newly made eligible for credits. It did not.

The credits are often justified as "paying for themselves" under the notion that they raise educational attainment and consequent earnings. The evidence does not support this justification.

The way the credits work may explain why they do not affect college-going. The authors point out that a family has to pay tuition an average of 9 to 10 months before receiving the credits. A family that struggles to afford college in the first place may thus be unable to benefit from the credits.

-- Linda Gorman