Designing Online Information Environments

In the wake of George Floyd’s death in 2020, companies like Target and Google expanded or launched initiatives aimed at supporting Black-owned businesses. One common strategy was to digitally label and highlight these businesses, making them easier for customers to find and support. Five years later, companies are reassessing these efforts amidst political pressure to dismantle diversity initiatives. Some, like Wayfair, have been growing their efforts, while others, such as Target, are considering scaling back. Underlying these decisions is an economic question: How does the design of online information environments influence market behavior?

As customers spend an increasing amount of time online, platforms play an important role as architects of the information environments they face. Changes to the design of online environments — such as labelling a business as minority-owned, adjusting search algorithms, or moderating and aggregating product reviews — can alter everything from which products we purchase to how misinformation spreads.

Several central themes have emerged from recent research on the design of online information environments. Racial discrimination is a pervasive challenge in online platform design. Choices about which information is provided to customers can facilitate or mitigate bias, or even actively support minority groups. Second, customers can systematically misinterpret the information provided, or not provided, by firms, distorting markets and leading to inefficient outcomes. The impact of information ultimately depends not only on its content but also on its salience and complexity. Another theme concerns distortions in online reviews, which can undermine their informational content. Some ways of aggregating information can lessen these effects. Understanding and accounting for the factors that influence ratings can make them more informative and enable better decision-making.

Discrimination on Online Platforms

Some early discussions about online platforms highlighted their potential to reduce race- and gender-based discrimination. The reasoning was straightforward: If discrimination was based on visible cues like race or gender, the relative anonymity of online transactions could help reduce it. However, as platforms evolved, there was a shift toward incorporating more personal information, such as names and photos. On the Airbnb platform, for example, hosts could decide whether to accept a guest after viewing their profile, which included a name and photo but little else. This allowed a host to reject a guest based on their name or appearance, something that would not have been possible on earlier platforms like Expedia where the booking process was more automated. The shift toward Airbnb opened up new markets for bookings, but also more opportunities for discrimination relative to traditional hotel markets.

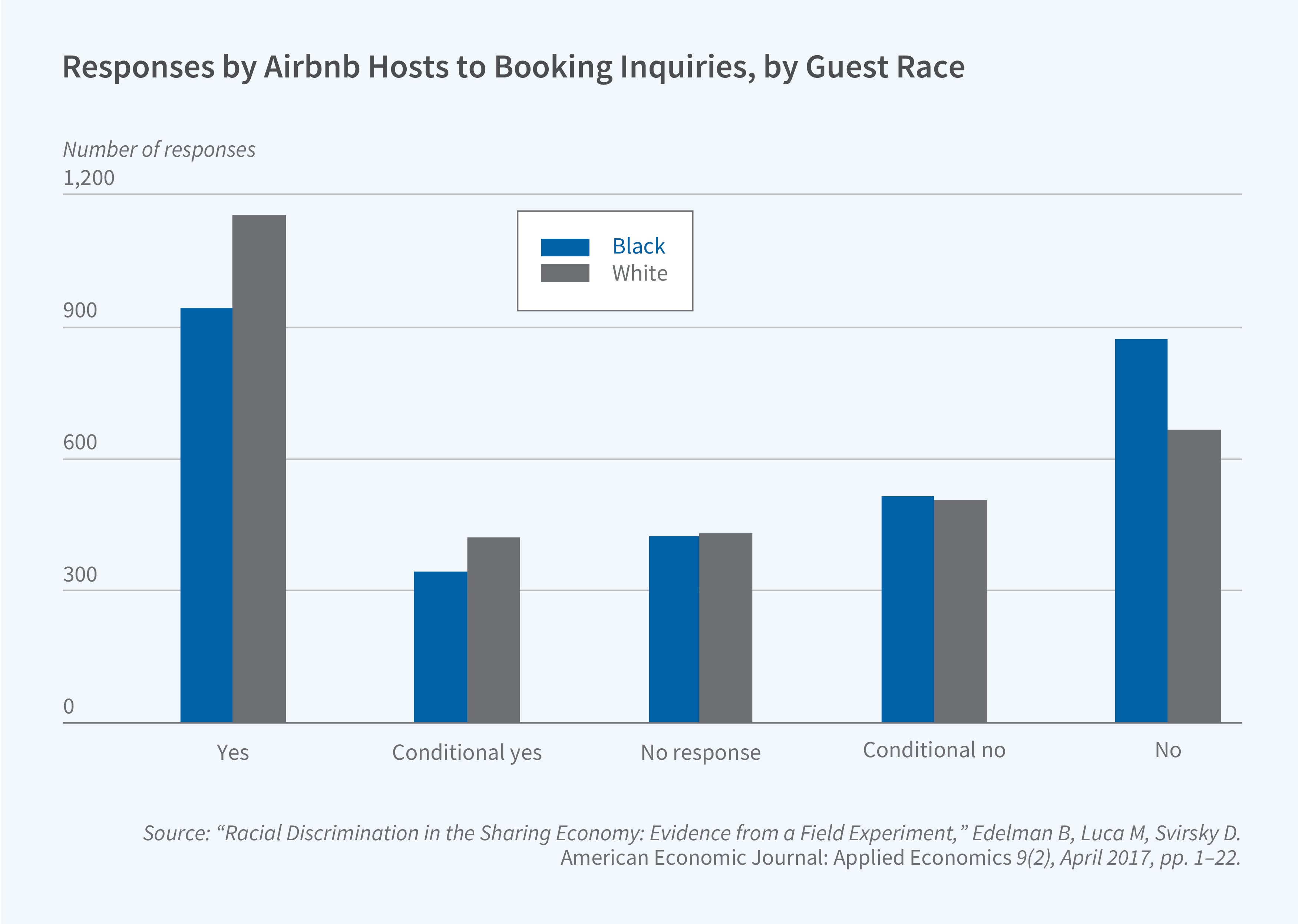

In an audit study on Airbnb, Ben Edelman, Dan Svirsky, and I found that providing hosts with profiles engendered discrimination: Guests with distinctively African-American names were roughly 16 percent less likely to be accepted than otherwise identical guests with distinctively White names.1 Discrimination was prevalent across different types of properties, but most pronounced among hosts with no prior history of hosting Black guests.

Expedia’s platform, in contrast, minimizes the opportunity for discrimination at the booking stage, as listing managers do not see names or photos prior to booking.

Ray Fisman and I have explored steps platforms might take to mitigate bias through changes in their information and choice environments.2 For example, consider the Airbnb feature known as “instant book,” through which a host allows renters to book their property without prior approval. While this feature was designed to make booking simpler and more convenient, it also makes it harder for hosts to discriminate since the transaction occurs before, rather than after, markers of race are revealed.

Although platforms have taken steps to mitigate discrimination, racial bias remains a challenge. The degree of bias can evolve over time. Elizaveta Pronkina, Michelangelo Rossi, and I document spikes in anti-Asian discrimination on Airbnb toward the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.3

Our earlier research prompted Airbnb to create a task force with the goal of evaluating various strategies to mitigate discrimination. The company ultimately implemented a series of changes, including offering more instant booking, making users agree to a new anti-discrimination policy, removing host photos from the main search results, and not showing guest photos until after the booking decision has been made.

To help business students prepare for these challenges in the workplace, Scott Stern, Devin Cook, Hyunjin Kim, and I developed a case study focused on how Airbnb’s leadership team might approach the challenge of addressing discrimination on the platform.4 Other platforms, including Uber and LinkedIn, have now taken steps to understand and mitigate bias on their platforms.

While some platform designs can facilitate discrimination, others can support marginalized groups. For example, one strategy companies including Walmart, Target, Wayfair, and Yelp have explored is to make it easier for customers to find Black-owned businesses through new search tools and business labels. If consumers have a latent demand to support Black-owned businesses, these steps can reduce search frictions and allow consumers to act on this demand.

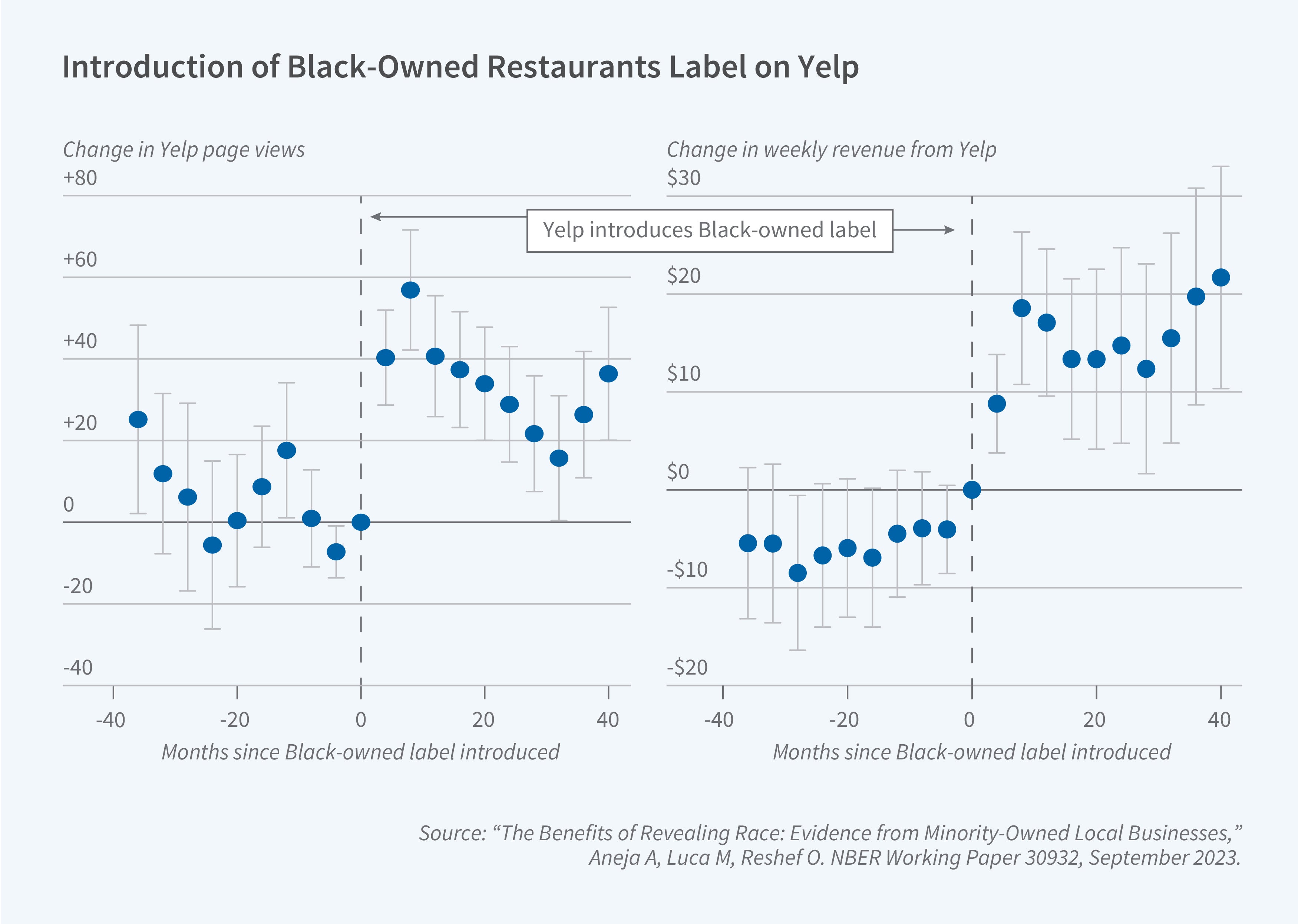

Abhay Aneja, Oren Reshef, and I investigated a feature that Yelp launched to allow users to find Black-owned restaurants more easily.5 Businesses identified as Black-owned experienced increased demand, as indicated by more calls, more delivery orders, and — using cell phone data— more in-person visits. Our findings suggest underlying pent-up demand to support Black-owned businesses.

An analysis of reviewer profiles suggests that much of the effect seems to be driven by White customers, reflecting consumer demand among White restaurant-goers to support Black-owned businesses. We also found that the effects are larger in geographic areas with less racial bias, as proxied by aggregated Implicit Association Test scores, suggesting that the impact of these features depends in part on underlying customer demand.

Information and Inferences

The economics of information has a rich history, analyzing concepts including uncertainty, adverse selection, screening, signaling, and more recently designing information in a world with costly communication, imperfect inferences, and rapidly evolving technology. Platforms and artificial intelligence offer expanded opportunities — from personalized information to AI-based decision aids — to provide and synthesize valuable information for decision-makers, sometimes overcoming and other times amplifying classic challenges.

A central result in information economics is that market forces have the potential to lead firms to disclose information voluntarily and completely, as long as the information is verifiable and the costs of disclosure are small. To see the mechanism, consider a case in which unknown sellers offer products of different quality and can credibly disclose the quality to prospective buyers. Customers become fully informed if quality is disclosed, but cannot distinguish quality when companies do not disclose. In this situation, the best businesses among those that do not disclose — those with the highest quality products — have an incentive to disclose and thereby separate themselves from the other non-disclosing firms. Applied iteratively, this logic leads all non-disclosing firms to ultimately disclose, so that in equilibrium consumers correctly infer the very worst from nondisclosure: the non-disclosing firms must have the lowest quality products. This highlights how voluntary disclosure can help solve asymmetric information problems in some settings, and points to policies that can increase the extent of disclosure. For example, some cities send hygiene scorecards that restaurants can voluntarily post on their doors, which is an attempt to make disclosure both low cost and verifiable.

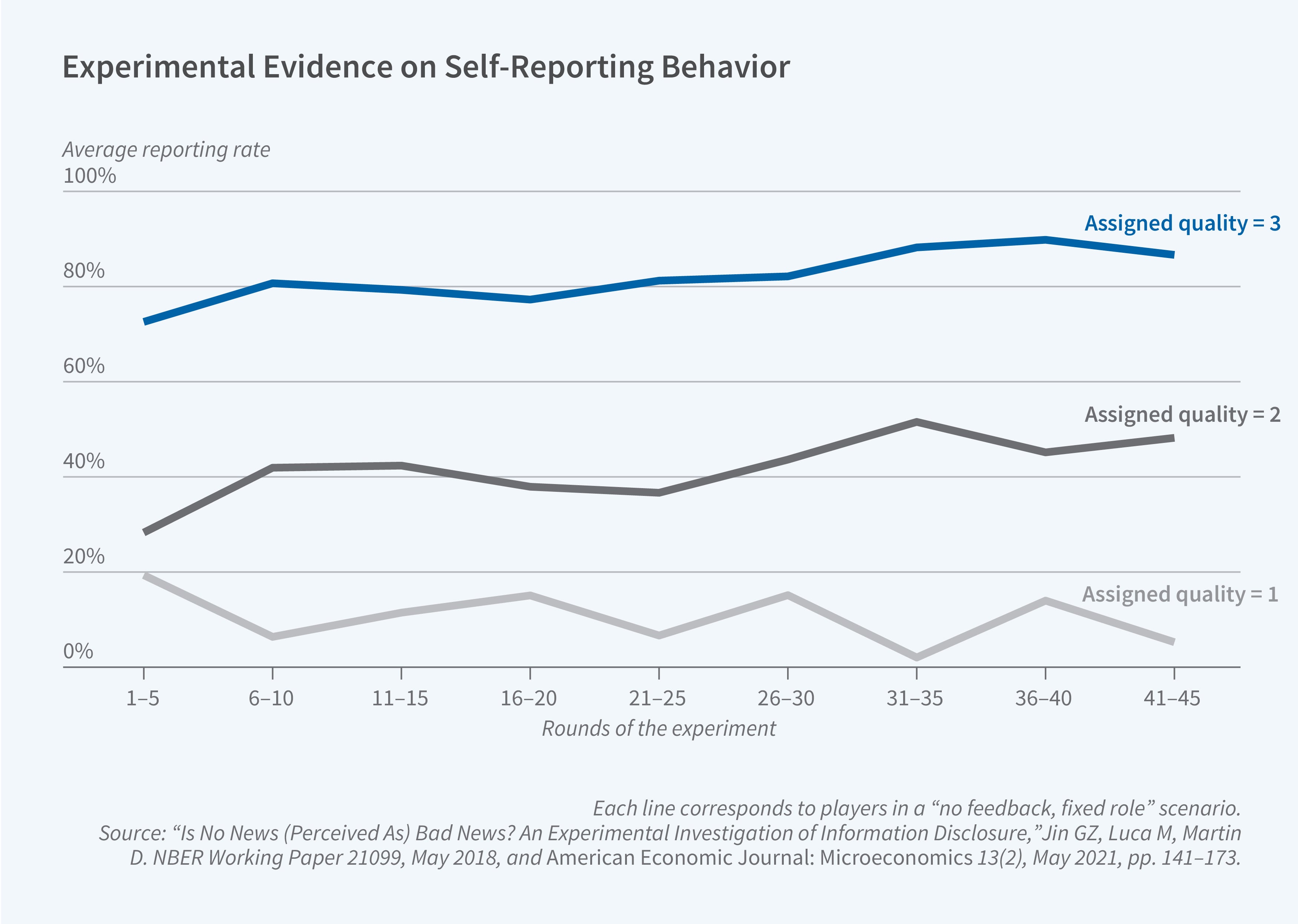

However, the unraveling result — in which only the lowest quality firms withhold information — also rests on strong assumptions around the inferences consumers make when businesses withhold. To directly test the unraveling hypothesis, Ginger Jin, Daniel Martin, and I ran a series of lab experiments focused on disclosure decisions and inferences.6 In contrast to theoretical predictions, we found that individuals provided with private information do not fully disclose it when the information is less positive and receivers are not sufficiently skeptical about nondisclosure. The results suggest limits to the foregoing narrative and also underscore that consumers are not as sophisticated as some models assume. Many consumers fail to interpret no information as bad news. Consumer education could ameliorate this and may be needed for voluntary disclosure to work in some settings, even if sellers have perfect information and a certification agency can verify their information for free.

Mandatory disclosure can, in principle, help to overcome these challenges, but is not a panacea, especially since companies have discretion not only about what information to disclose to customers but also how to disclose it. Even when disclosure is mandatory, as in the case of credit card agreements, mortgage statements, and privacy policies, important details can be buried in legalese or confusing formats, making it hard for consumers to identify and act on them. While disclosure can, at times, be complex by necessity, information complexity can also arise from the strategic incentives that companies face if consumers make systematic mistakes that are not in their own interest.

Jin, Martin, and I ran a series of experiments in which disclosure was mandatory but senders could decide how complicated to make the disclosure.7 Although policymakers may assume that required disclosures will ensure transparency, our experiments show otherwise: information senders with unfavorable news systematically introduce complexity.

The strategic complexity observed in disclosures by senders replicated the harmful effects of nondisclosure since many consumers did not sufficiently penalize complexity. Some of the consumers in the experiment overestimated their ability to accurately synthesize complex information and, in the process, made mistakes that benefited the information sender.

For policymakers, this highlights the value of considering not only what information should be provided to consumers but also how to present it. In a world where people are bombarded with complex information, there can be value in presenting relevant information in a way that makes it easy for consumers to make decisions. Daisy Dai and I found that a pilot study that shifted the visible prominence of information changed consumer responses to the information.8

Platforms offer new opportunities for businesses and policymakers to revisit their approaches to disseminating information. For instance, health agencies are increasingly looking at social media advertisements and disclosure via platforms to reach stakeholders and to complement information they are already providing. Using data from Facebook and Instagram, Susan Athey, Kristen Grabarz, Nils Wernerfelt, and I conducted a meta-analysis of more than 800 experiments run by 174 public health-related organizations, such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, involving roughly $40 million in advertising.9 We had access to the near universe of experiments run by these organizations on the platforms, so we were able to estimate the average effect of all of the interventions that were tested, rather than the effect of any one particular campaign. For interventions aimed at behavioral change around COVID-19, our results suggest that the interventions cost an estimated $5.68 for each additional person vaccinated.

Each individual experiment had limited samples, making it hard for many agencies to assess whether their specific campaigns were effective. This points to both the potential and the challenges of social media advertising as a tool for policy-related organizations. Larger experiments, more efforts aimed at meta-analyses, and further focus on boundary conditions can help to develop frameworks that can be used to understand the conditions under which such campaigns are likely to be effective.

Challenges to the Quality of Online Reviews

In addition to disseminating information directly from businesses and policymakers to households, platforms have also facilitated the growth of user-generated content. Reputation systems, both stand-alone sites like TripAdvisor and integrated sites on e-commerce platforms like Airbnb, are prime examples. They make decisions about how to generate, aggregate, and display content.

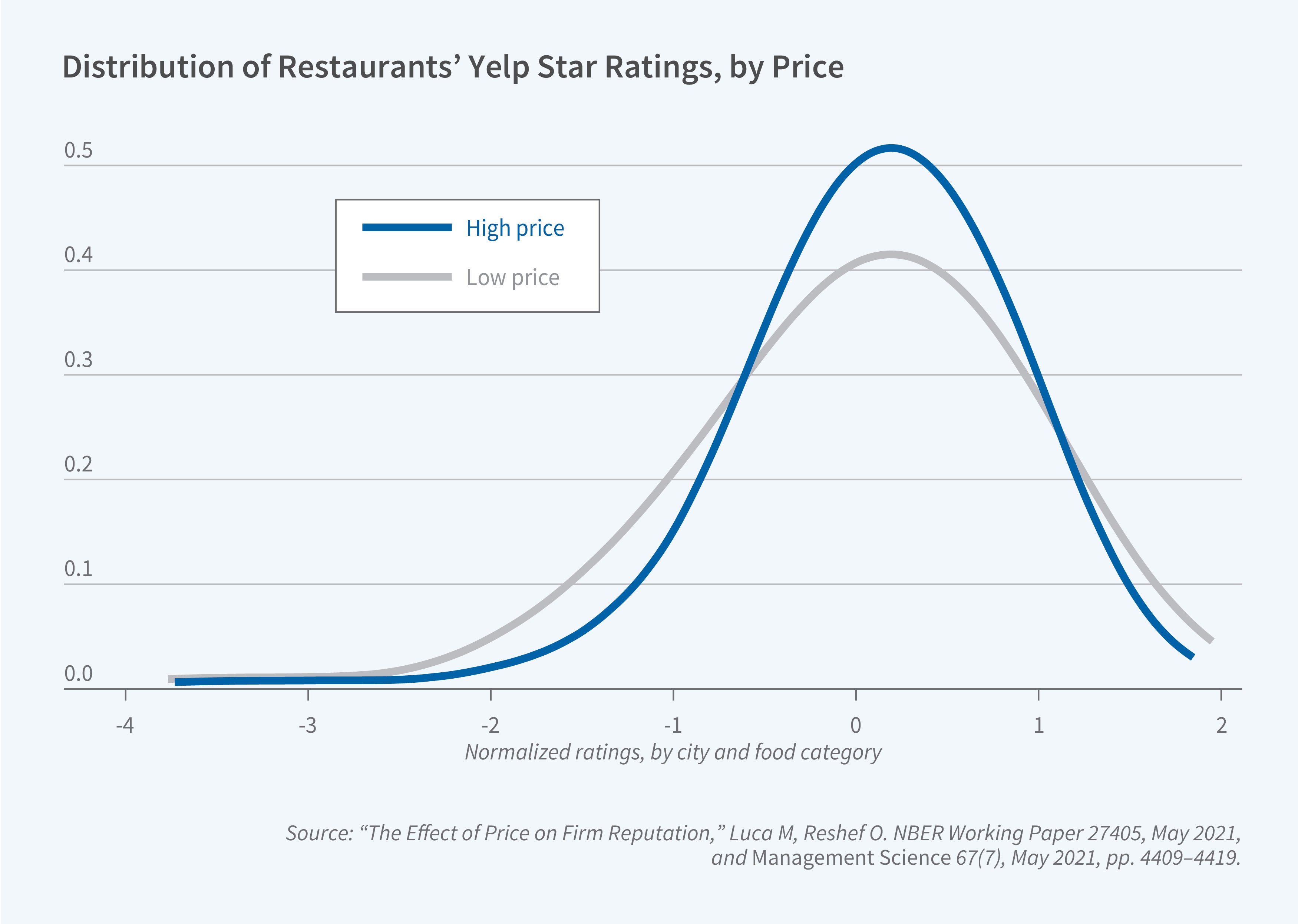

Reshef and I study whether ratings reflect customer perceptions of quality, or quality adjusting for prices.10 Since price sensitivity can vary across customers and prices can change over time, understanding the impact of prices on ratings is relevant for customers and platforms alike. Looking at daily data on delivery orders placed through Yelp, we found that a price increase of 1 percent was associated with a decrease of 3–5 percent in the average rating. The price effect on ratings does not seem to be driven by consumer reactions to price changes but by changes in absolute price levels. This result connects to long-standing economics questions about the link between price and reputation. For restaurants, this points to the reputational effects of pricing strategies. Price changes thus complicate the interpretation of average ratings by customers and by platforms.

A key open question concerns how to aggregate reviews. Suppose that a restaurant has reviews that span a decade. Should they all get the same weight? Should older ones be down-weighted? If a platform has insight into the types of reviews that are more or less informative, they can adjust the aggregation accordingly. Dai, Jin, Lee, and I explore the aggregation problem and develop a model that endogenously assigns more weight to newer reviews relative to older reviews and to “elite” reviewers relative to “non-elite” ones.11 The core insight is that in most realistic models of user behavior, it is suboptimal — from an informational content perspective — to reveal simple arithmetic averages. Companies can use this insight to develop more informative aggregate ratings.

A related challenge is dealing with fake reviews, which can undermine trust in the system and reduce the value of the information provided to potential customers. Georgios Zervas and I analyzed reviews flagged by an algorithm as suspicious; the results suggest that businesses facing tougher competition or suffering from a poor reputation were more likely to engage in review fraud.12 Data from a related sting operation by Yelp showed consistent patterns. Platform operators must make decisions about how to handle suspicious reviews.

Putting It All Together

Online information ecosystems play an increasingly central role in modern society. Thoughtful design choices can help platforms present information in ways that support better decision-making and fairer outcomes. As digital platforms continue to evolve, carefully considering how information is provided, aggregated, and interpreted can contribute to more efficient markets, greater transparency, and improved outcomes for customers and businesses alike.

Endnotes

“Racial Discrimination in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” Edelman B, Luca M, Svirsky D. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(2), April 2017, pp. 1–22.

“Fixing Discrimination in Online Marketplaces,” Fisman R, Luca M. Harvard Business Review 94(12), December 2016, pp. 88–95.

“Scapegoating and Discrimination in Times of Crisis: Evidence from Airbnb,” Luca M, Pronkina E, Rossi M. NBER Working Paper 30344, March 2023, and published online as “The Evolution of Discrimination in Online Markets: How the Rise in Anti-Asian Bias Affected Airbnb During the Pandemic,” Marketing Science, February 2024.

“Racial Discrimination on Airbnb (A),” Luca M, Stern S, Cook D, Kim H. Harvard Business School Case Collection, August 2022.

“The Benefits of Revealing Race: Evidence from Minority-Owned Local Businesses,” Aneja A, Luca M, Reshef O. NBER Working Paper 30932, September 2023, and American Economic Review 115(2), February 2025, pp. 660–689.

“Is No News (Perceived As) Bad News? An Experimental Investigation of Information Disclosure,” Jin GZ, Luca M, Martin D. NBER Working Paper 21099, May 2018, and American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 13(2), May 2021, pp. 141–173.

“Complex Disclosure,” Jin GZ, Luca M, Martin DJ. NBER Working Paper 24675, February 2021, and Management Science 68(5), August 2021, pp. 3236–3261.

“Digitizing Disclosure: The Case of Restaurant Hygiene Scores,” Dai W, Luca M. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 12(2), May 2020, pp. 41–59.

“Digital Public Health Interventions at Scale: The Impact of Social Media Advertising on Beliefs and Outcomes Related to COVID Vaccines,” Athey S, Grabarz K, Luca M, Wernerfelt N. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(5), January 2023.

“The Effect of Price on Firm Reputation,” Luca M, Reshef O. NBER Working Paper 27405, May 2021, and Management Science 67(7), May 2021, pp. 4409–4419.

“Aggregation of Consumer Ratings: An Application to Yelp.com,” Dai W, Jin G, Lee J, Luca M. Quantitative Marketing and Economics 16, December 2017, pp. 289–339.

“Fake It Till You Make It: Reputation, Competition, and Yelp Review Fraud,” Luca M, Zervas G. Management Science 62(12), January 2016, pp. 77–93.