Labor Market Adaptation to Rising Import Competition

In Places versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustment to Globalization (NBER Working Paper 33424), David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, Maggie R. Jones, and Bradley Setzler examine how local labor markets and the workers in these markets adjusted to increased Chinese import competition in the first two decades of this century. They analyze comprehensive employer-employee data from the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics program over the 2000–19 period. Their analysis exploits location-specific variation in the impact of growing imports from China following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, which is due to the heterogeneity in industry composition across local labor markets.

US manufacturing job losses from Chinese import competition have been offset by employment growth in low-wage service sectors, but few former manufacturing workers have shifted to these sectors.

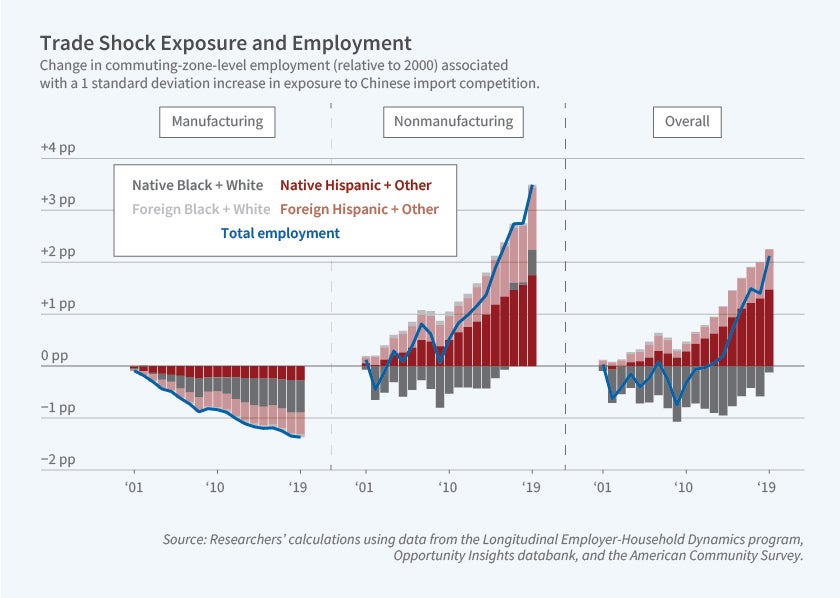

The study finds that while trade-exposed regions more than fully recovered their trade-induced employment losses after 2010, incumbent workers in those regions did not experience comparable recovery. Manufacturing employment in trade-exposed commuting zones continued declining steadily throughout the study period. Yet, by 2019, nonmanufacturing employment in these regions had expanded enough to more than offset manufacturing job losses.

Conventional economic theory predicts adjustment through geographic mobility, sectoral reallocation, and temporary nonemployment. However, the researchers find that cross-sector mobility of former manufacturing workers accounted for only 14 percent of the manufacturing employment decline. Measured another way, it accounts for only 6 percent of nonmanufacturing employment growth. Moreover, instead of seeing increasing out-migration, trade-exposed regions experienced reduced outward migration of incumbent workers alongside reduced inflows of workers from other regions.

The employment recovery in trade-exposed regions stemmed primarily from inflows of young adults who were below working age when China joined the WTO and the entry of foreign-born workers obtaining their first US jobs in these regions. These new entrants differ significantly from displaced manufacturing workers — they are disproportionately native-born Hispanics, foreign-born immigrants, women, and college-educated individuals.

Rising imports transformed the earnings structure of affected regions. Lost manufacturing jobs were predominantly middle- and high-paying positions, while new nonmanufacturing employment was concentrated in low-wage service sectors like healthcare, education, retail, and hospitality. By 2019, 62 percent of net employment growth in trade-exposed regions occurred in the bottom tercile of the earnings distribution.

Employment-to-population ratios in trade-exposed regions remained depressed through 2019 despite employment growth. This reflects both demographic shifts and differential labor market participation. There was a substantial drop in the native-born, White, non-college-educated male share of employment among workers aged 40–64 in the most trade-exposed regions.

The study underscores how adjustment to trade shocks can be generational, occurring not through the adaptation of incumbent workers but through a demographic transformation of the workforce.

David Autor acknowledges support from the Hewlett Foundation, Google, the NOMIS Foundation, Schmidt Sciences, and the Smith Richardson Foundation. David Dorn acknowledges support from the University of Zurich’s Research Priority Program “Equality of Opportunity.” Gordon H. Hanson acknowledges support from the Hewlett Foundation and the Generation Foundation.