Gifted Education Boosts Achievement of Disadvantaged Boys

Girls are more likely to go to college than boys. One explanation for this pattern is that boys have weaker noncognitive skills, such as self-discipline, than girls. In Can Gifted Education Help Higher-Ability Boys from Disadvantaged Backgrounds? (NBER Working Paper 33282), David Card, Eric Chyn, and Laura Giuliano examine the impact of gifted education on boys from low-income or non-English-speaking families, focusing on noncognitive skill development and college enrollment.

The researchers study a gifted program in a large Florida school district. Gifted students receive an education plan with curricular and social/emotional goals aimed at maintaining engagement in school. They meet with a specialist every two years and at the transitions to middle and high school for additional guidance. In 4th and 5th grades, gifted students are assigned to separate classrooms taught by teachers with specialized training in gifted education. All these features could contribute to noncognitive skill development.

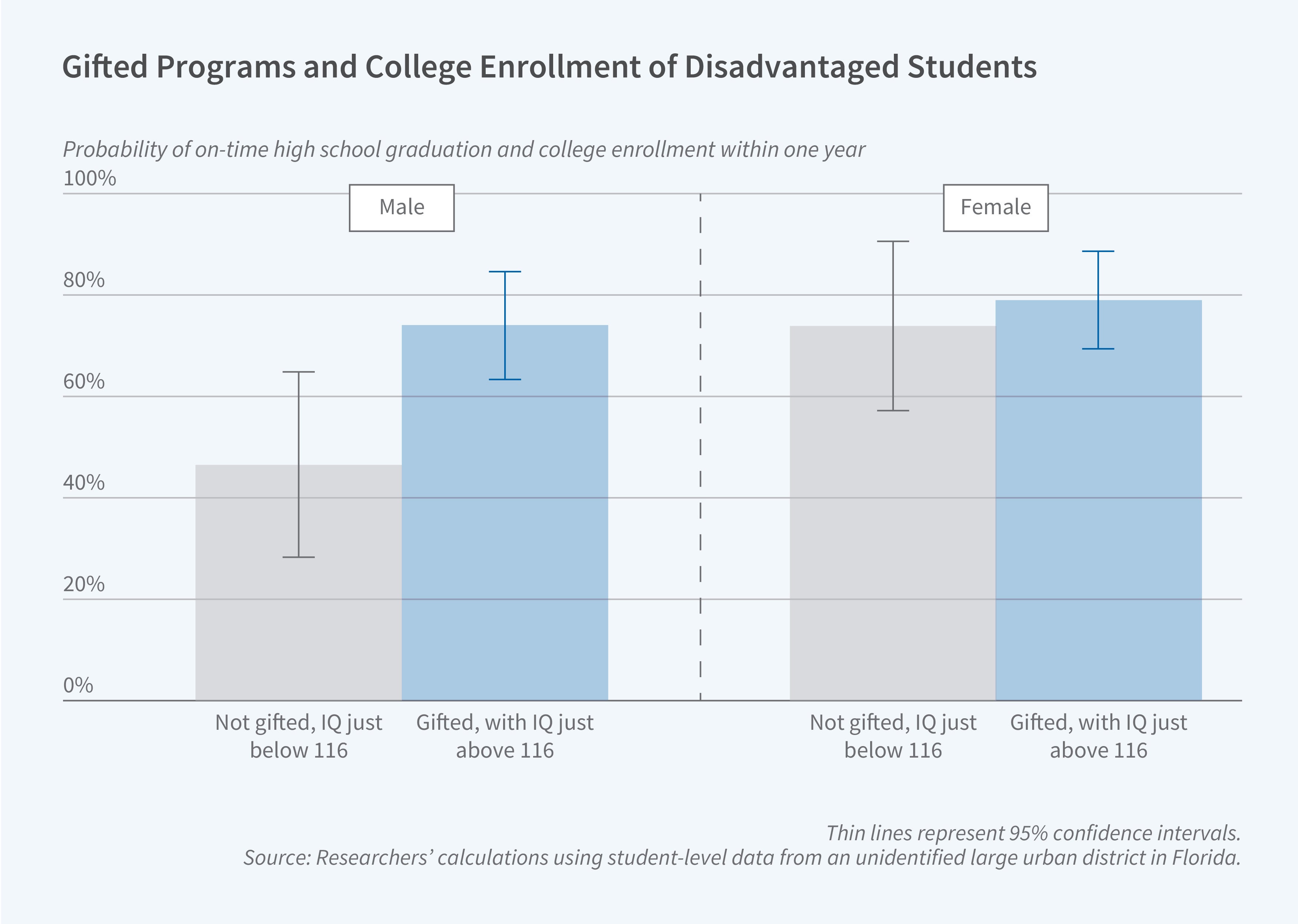

In a large Florida school district, being classified as “gifted” led to a 25–30 percent increase in on-time high school graduation and college entry rates for disadvantaged boys.

The study focuses on English language learners and students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunches — indicators used by the state to proxy for a disadvantaged background. To qualify as gifted, these students must score at least 116 on an IQ test — roughly the 84th percentile of the score distribution. The researchers identify 5th grade enrollees in the district who scored between 106 and 124 on an IQ test. Among this narrow set of students, those with scores just above 116 have a much higher probability of entering the gifted program than those scoring just below. They then use a regression discontinuity approach to compare schooling outcomes between these two groups of students, isolating the effects of gifted status on “complier” students whose entry to the program depends on having an IQ score above 116.

They show that entry to the gifted program raises the probability that disadvantaged boys graduate high school on time and enter college the next fall from a rate of only 50 percent if they miss the gifted threshold to 75 percent. For disadvantaged girls with scores near 116, in contrast, the program has little effect: their rate of on-time college entry is about 75 percent regardless of whether they enter the gifted program. In other words, entry to the gifted program closes the gender gap in on-time college entry, enabling boys to achieve about the same rate as girls with similar IQs.

The researchers find that participation in the gifted program had no effect on the standardized test scores or PSAT exam scores of boys or girls, suggesting that gifted services do not increase the cognitive abilities of students. However, they find relatively large effects for boys on course selections and course grades — outcomes that are often interpreted as indicators of noncognitive skill when cognitive ability is held constant. Marginally eligible boys were more likely to enroll in advanced tracks in middle school math and language arts and to take Algebra I before 9th grade. They also took almost twice as many Advanced Placement courses in high school. These effects were large enough that boys’ rates caught up to those of girls with similar IQs. Despite having a more challenging curriculum and higher-achieving classmates, gifted boys earned substantially higher course grades in high-school mathematics — narrowing (but not fully closing) a large gender gap — and did not experience any negative impacts on their grades in other subjects.

— Greta Gaffin

The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, through grant R305C200012 to the National Center for Research on Gifted Education.