Economic Growth, Cultural Traditions, and Declining Fertility

When nations experience rapid economic modernization, traditional family values can clash with new social realities and result in sharply declining birth rates. This insight helps to explain why some developed countries have much lower current fertility rates than others, despite having had higher rates in the recent past.

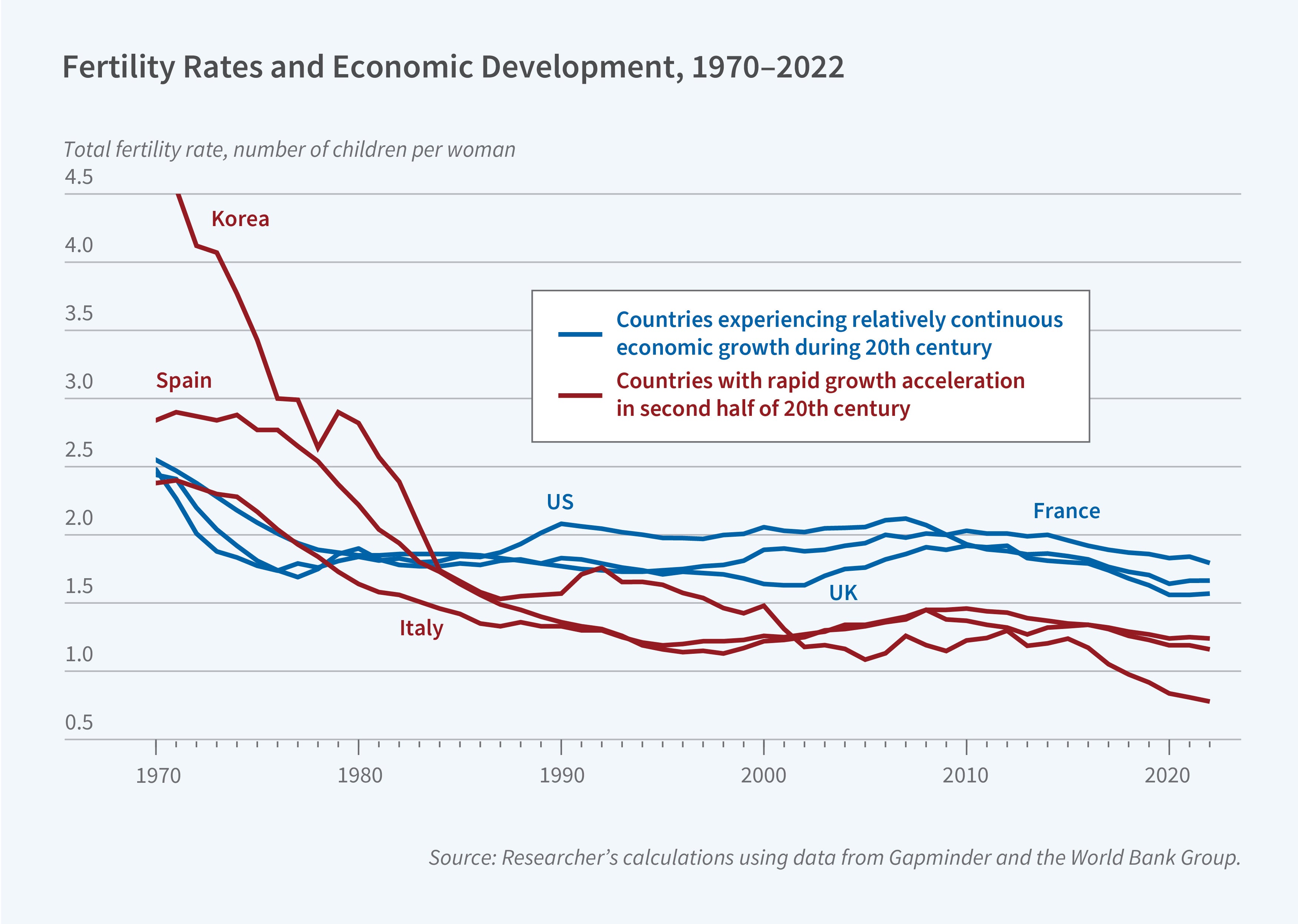

In Babies and the Macroeconomy (NBER Working Paper 33311), Claudia Goldin examines fertility patterns across 12 developed nations. She divides the countries into two groups: one, comprising Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, the UK, and the US, that experienced relatively steady economic growth throughout the twentieth century, and the other, Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Portugal, and Spain, that underwent extremely rapid economic development after 1950.

Cross-country evidence shows that rapid economic growth coupled with persistent traditional gender roles can result in sharp fertility declines, particularly when women disproportionately supply unpaid domestic labor.

The countries in the first group have maintained moderate fertility rates, starting around 2.5 children per woman in the 1970s and then ranging from 1.5 to 2 children from the 1980s until the 2020s. Countries in the second group had higher initial fertility rates in the 1970s (ranging from 2.5 to 4.5 children) but experienced dramatic declines in subsequent decades. These countries have seen fertility rates plummet to “lowest-low” levels below 1.3 children per woman after 2000, reaching as low as less than 1.0 child per woman. While fertility rates have declined for the first group of countries, their post-2000 levels remain considerably higher than those of the second group.

Goldin suggests that rapid economic change can create both generational and gender conflicts that affect fertility decisions. In countries that undergo sudden economic modernization, men often remain attached to traditional family structures while women embrace new economic opportunities. This can result in tension over fertility choices. Goldin explains that “what women require of men’s time to raise a family and be members of a modern labor market may exceed the time their more tradition-bound spouses, or future spouses, are willing to offer.” The speed of economic growth per se is potentially less important than the societal transformations that go with it, as nations that are communal, tradition bound, and rural become more urban and better connected.

Time-use data support this hypothesis. In countries in the second group, women perform at least 2.5 hours more unpaid household and care work per day than men, compared with 0.8 to 1.7 hours of such labor for women in the first group of countries. This gender disparity in domestic labor exhibits a strong negative correlation with fertility rates. For example, Japan and Italy show gender differences of about 3 hours in unpaid work and have fertility rates of 1.36 and 1.27, respectively, while Sweden’s 0.8-hour difference corresponds with a higher 1.7 fertility rate.