The Price of Consolidation: Evidence from Anesthesia Practice Rollups

In a “rollup,” an outside investor consecutively acquires many of the small firms operating in a particular local market, consolidating them into a single large firm. Unlike mergers, which involve only two firms and trigger regulatory attention when the firms collectively exceed a certain size, rollups have flown under the antitrust radar until a recent Federal Trade Commission (FTC) case targeting a rollup of anesthesia practices in Texas. Rollups have become increasingly important, particularly in the healthcare industry.

In Painful Bargaining: Evidence from Anesthesia Rollups (NBER Working Paper 33217), Aslihan Asil, Paulo Ramos, Amanda Starc, and Thomas G. Wollmann study the competitive effects of the rollups implicated in the FTC’s case, as well as 18 similar rollups that together cover 20 percent of the US population. Combining data on clinicians and their employers from the Doctors and Clinicians national file, data on acquisitions from PitchBook, and data on insurance claims for medical procedures, the researchers build a comprehensive picture of the anesthesiology industry since the early 2010s. They define “rollups” as instances in which a single buyer acquires at least two practices in a single market using outside capital.

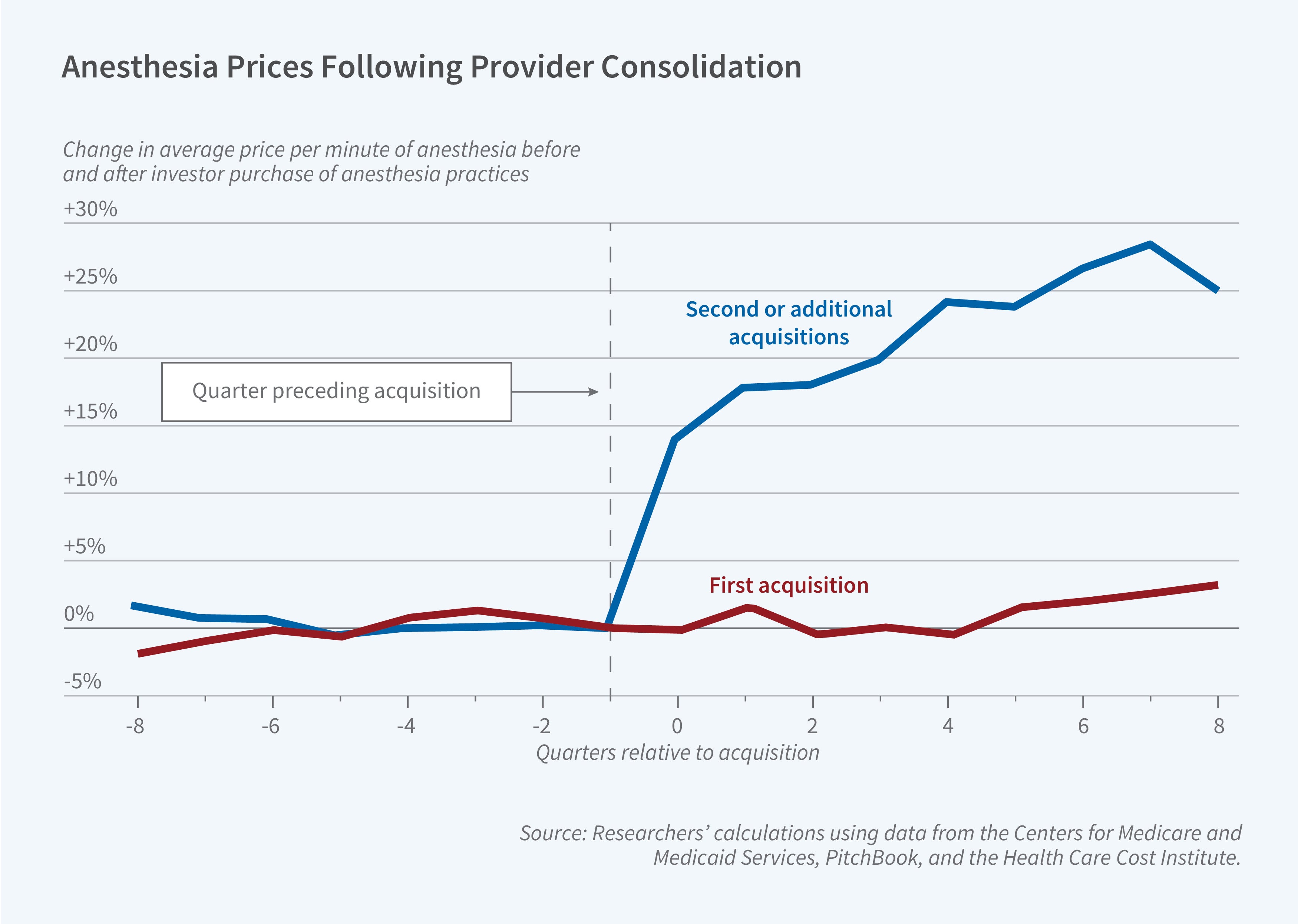

When an investor group acquires one practice in a market, prices do not change, but multiple acquisitions are associated with an average price increase of 18 percent within six months.

Rollups dramatically reshape local market structure by increasing concentration. To measure the effect of rollups on prices, the researchers conduct an event study. To rule out the possibility that investment funds always pressure practices they acquire to increase prices, the researchers first conduct their event study for the first practice acquired in each rollup. They do not find any evidence of a price increase in those cases. It is only when the investors own multiple practices that price increases emerge. They find an 18 percent average price increase in the first six months following subsequent, “add-on” acquisitions. Prices ultimately rise by 25 to 30 percent.

The researchers also test for but do not find evidence that the rolled-up practices deliver higher quality services. Qualitative evidence also suggests that while acquisitions typically affect business strategies such as price setting, they rarely affect clinical practice. Prices rise rapidly following rollups despite the fact that hospitals typically have long-term contracts with anesthesiology providers. One way rollup sponsors are able to sidestep this issue is by moving physicians from lower-price practices acquired during the rollup to higher-price practices, allowing an immediate shift to the prices charged by the latter.

The authors model supply and demand of anesthesia services to study potential interventions to improve consumer welfare. They find that divestitures are more powerful than health policy solutions, including price regulation.

— Shakked Noy

Researcher Thomas G. Wollmann thanks the Fama-Miller Center, Becker Friedman Institute Healthcare Initiative, and William Ladany Research Fund for support.