Retirees Relocate for Income Tax Exemptions

In 2013, the Portuguese government offered foreign retirees relocating to Portugal a 10-year tax exemption on their foreign-source pension income, provided their country of origin had a tax treaty with Portugal. As the number of immigrant retirees grew, the amount of forgone income taxes grew, reaching €1.5 billion, or about 0.6 percent of GDP, by 2021. In that year, the tax exemption was replaced by a 10 percent rate. In 2024, the exemption was repealed.

In Pensioners Without Borders: Agglomeration and the Migration Response to Taxation (NBER Working Paper 32890), Salla Kalin, Antoine B. Levy, and Mathilde Muñoz examine Portugal’s tax experiment and find that individuals who were aged 55 and older, particularly those who were wealthier, more educated, and from higher-tax countries, were willing to resettle in exchange for lower taxes.

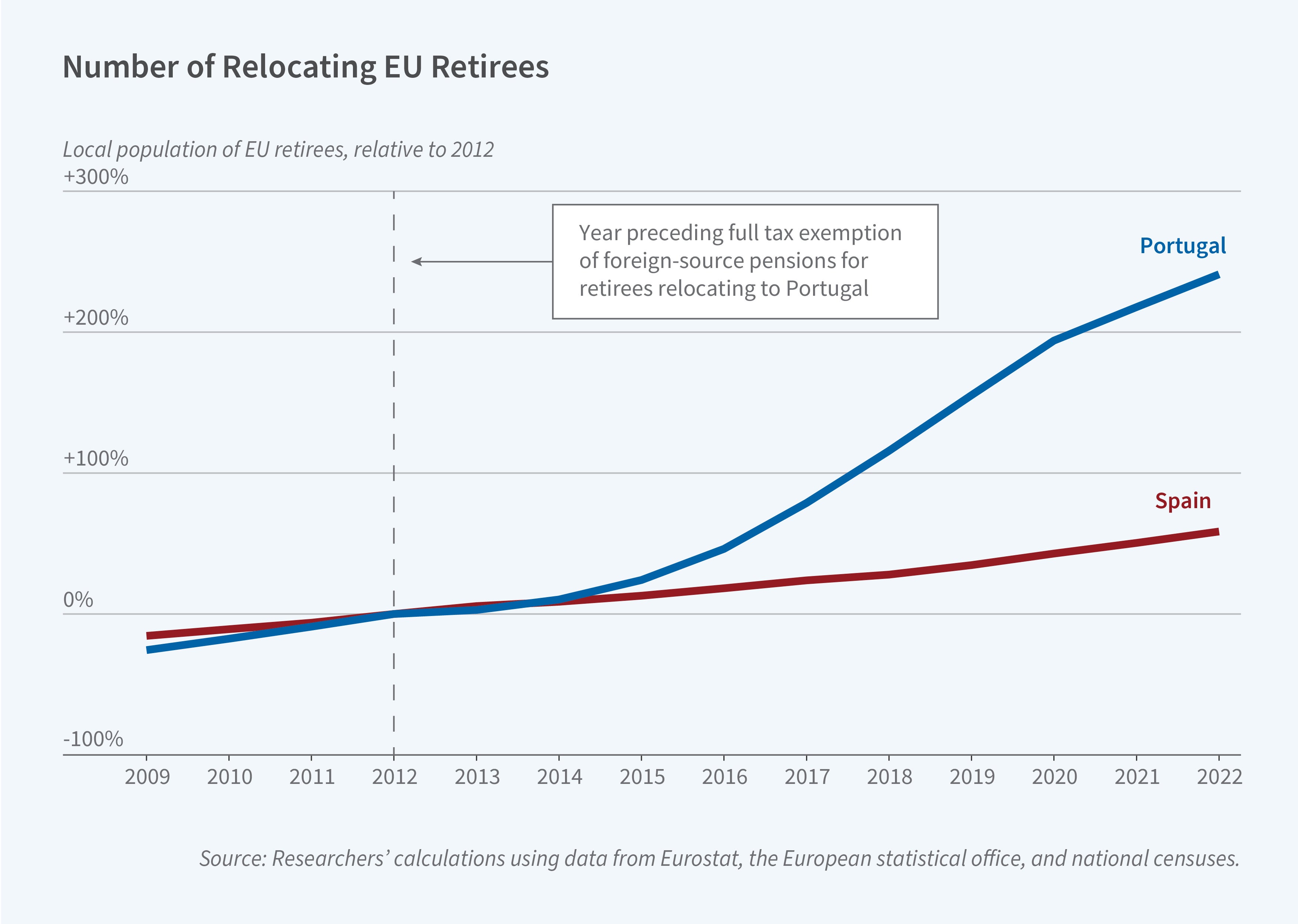

Data from Eurostat, national population registers, and censuses show that Portugal’s inflows of foreign retirees and working-age immigrants were similar from 2008 to 2012. After the 2013 tax reduction, foreign retiree inflows rose sharply. By 2017, when the number of foreign pensioners in Spain was about the same as in 2012, the number in Portugal had tripled — a 200 percent increase — compared to 2012. The number of working-age individuals moving to the two countries also remained stable. Tax-induced migration to Portugal was larger for retirees from countries with longer expected retirements and higher taxes. The inflows of retirees to Portugal decreased substantially when the 10 percent tax went into effect in 2021.

To pinpoint tax changes as the driver of immigration inflows, the researchers compare retiree inflows to Portugal with those to Spain. The inflows to the two countries were similar from 2009 to 2012 but diverged beginning in 2013. Using data from Spain and other European countries, the researchers estimate that a 10 percent increase in the net-of-tax income that a pensioner receives in a country — the equivalent of a drop in the income tax rate from 20 percent to 12 percent, meaning the pensioner would keep 88 percent rather than 80 percent of pre-tax income — would increase the number of pensioners choosing to live in that location by between 15 and 20 percent.

To learn more about the attributes of migrating pensioners, it is necessary to obtain data from the countries they are leaving. The researchers were able to access data from Finland on Finns who migrated to other nations. The database includes information on education, lifetime earnings, capital income, and past firm and establishment affiliations. The data show that the Finns who migrated to Portugal or Spain prior to 2013 were similar and that they were more likely to be in the top decile of incomes when they worked, more likely to receive capital income, more likely to be highly educated, and more likely to be married. Their average pension was €1,600 a month.

After 2013, Finnish retirees in Portugal received a much higher average pension — €3,500 — than those in Spain. Education levels and the probability of receiving income from capital also rose. The share of married individuals dropped.

Finland unilaterally ended its double taxation treaty with Portugal in 2018 “to protest the zero tax rate granted to foreign pensioners.” Sweden followed suit in 2022. Without treaties, retirement income was taxed at the rates existing in the countries where it originated. Portugal’s Finnish population peaked in 2018 at five times its 2013 level. Though some Finns left after the treaty was repealed, the number of retired Finns in Portugal stabilized by 2023 at about three times the pre-2013 level. The number of Swedes living in Portugal followed a similar trajectory before and after Sweden unilaterally suspended its tax treaty. The number of Finns and Swedes in Portugal remained permanently at higher levels even after the tax treaty repeal, with the stark initial increases not fully offset by later return migration. The researchers’ findings suggest that such permanent changes in residence choices induced by temporary tax changes could justify aggressive tax policies designed to trigger a “big pull” of migrants from a certain demographic.

— Linda Gorman