Food Assistance for Families During COVID-19

Unemployment can jeopardize the ability of households to purchase enough food. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when unemployment rose rapidly, 27 percent of households with children reported that they could not always afford enough food. In The Effects of Lump-Sum Food Benefits during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Spending, Hardship, and Health (NBER Working Paper 33199), Lauren L. Bauer, Krista J. Ruffini, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach examine the effects of a transfer program that provided vouchers for food purchases to American families with children during this period.

Receipt of P-EBT payments during the pandemic reduced reported food insufficiency by 30 percent.

More than 20 million low-income children in the United States receive free or reduced-price breakfasts and lunches at school. Students qualify for free meals if their family income is less than 130 percent of the poverty line, if their household receives benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or if they attend a school with a school-wide free meals program. During the COVID-19 pandemic, school closures meant that these children were no longer receiving such meals. In response, Congress authorized the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT), a program that provided vouchers for food purchases to households that otherwise would have received free or reduced-price meals. The payments per student were calculated by multiplying the daily federal free breakfast and lunch reimbursement ($5.70 in the continental US) by the number of days schools were closed. States typically made one-time payments that averaged $311 per child; these payments were added to the balances on EBT cards. The amount of these transfers was roughly twice the maximum monthly SNAP benefit per person for a family of three.

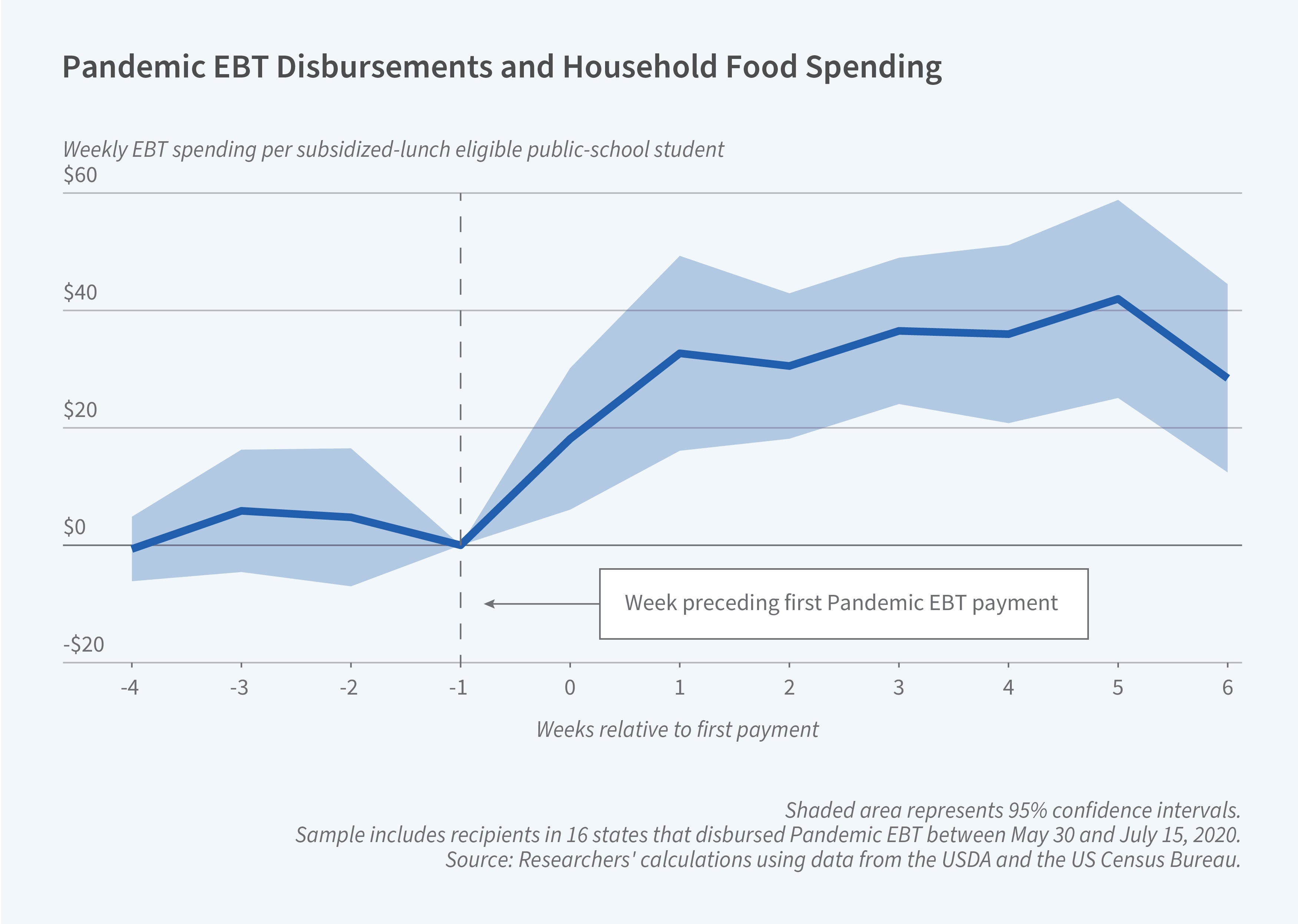

The researchers study families that were income-eligible to participate in the SNAP program, many of whom still report food insecurity. They exploit the fact that different states implemented the P-EBT programs at different times to compare the spending of P-EBT recipients with that of other broadly similar households. In the six weeks after P-EBT payments were issued, on average, per-student food spending increased by between $18 and $42. Families were also 30 percent less likely to report food hardship during this period, and the share of children reported to be in very low food security was cut in half. P-EBT receipt was also associated with an improvement in maternal mental health.

The data suggest that families did not use the full benefit immediately after disbursement but rather chose to increase spending over at least 6 weeks. The researchers find no improvement in households’ perceived future financial security after P-EBT receipt. This may be because families did not think they would receive additional payments and therefore anticipated returning to food insecurity after the P-EBT had run out.

— Greta Gaffin

Bauer and Ruffini acknowledge support from Healthy Eating Research (Grant 111326).