Gender, Career Opportunities, and the Relocation Decisions of Couples

A new study of German and Swedish data finds that men’s earnings increase following a couple’s move to a new commuting zone, while women’s earnings stay the same or decline at the outset. Couples are also more likely to relocate when a man is laid off than after a woman is.

These findings suggest that couples’ relocation decisions are driven by traditional gender norms rather than efforts to maximize household income, according to Moving to Opportunity, Together (NBER Working Paper 32970), by Seema Jayachandran, Lea Nassal, Matthew J. Notowidigdo, Marie Paul, Heather Sarsons, and Elin Sundberg.

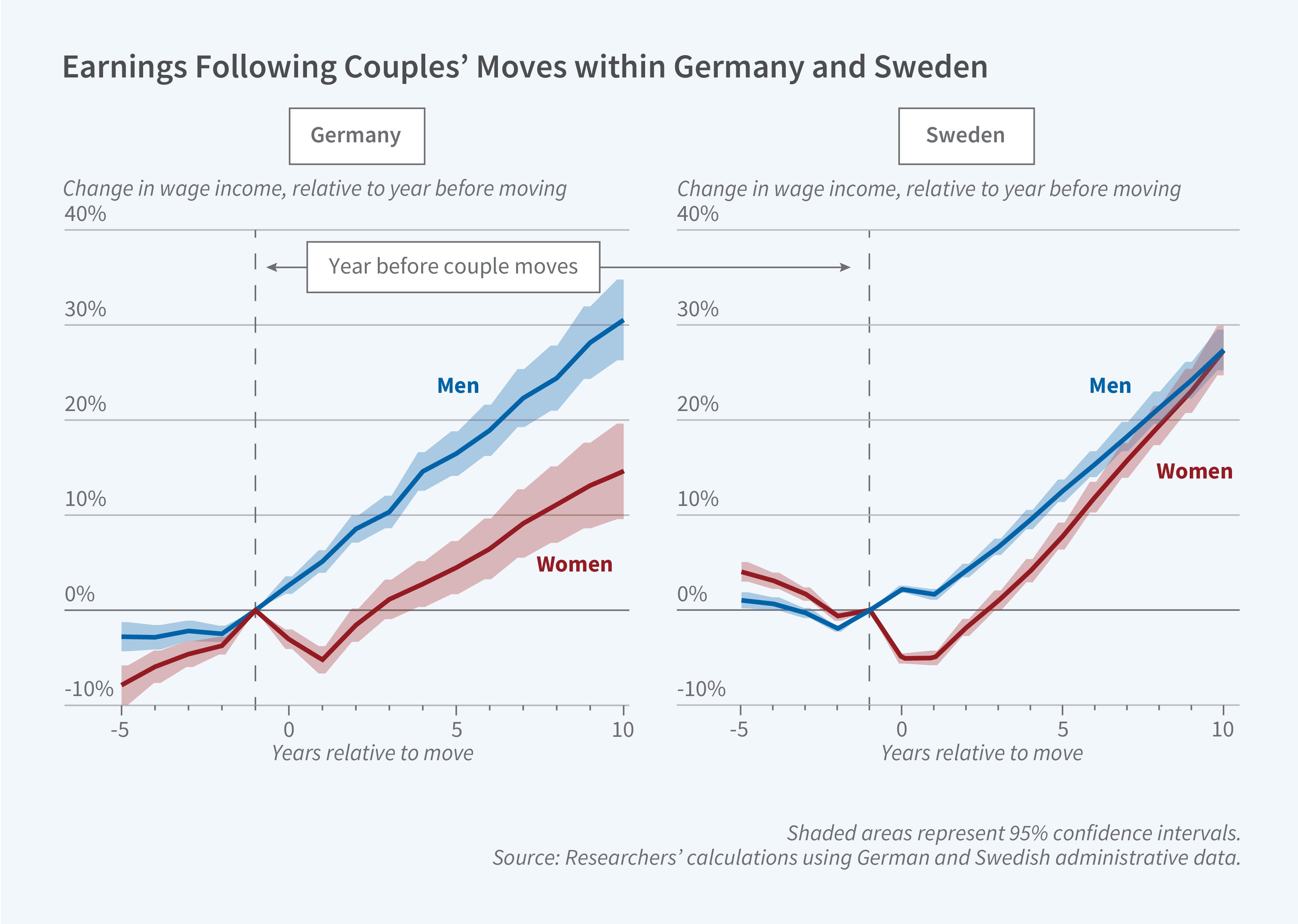

Both men and women experience long-run earnings increases following a move, but men’s earnings rise immediately, while women’s drop and later rebound.

The study focuses on couples who moved between commuting zones between 1995 and 2007 in Sweden and between 2001 and 2011 in Germany. The sample is restricted to couples with at least one spouse between the ages of 25 and 45 at the time of the move and with neither spouse over the age of 60 or under the age of 18. In both Sweden and Germany, men have higher earnings and employment rates than women, but the gender gap is larger in Germany than in Sweden.

The researchers find that men’s earnings increase by 10 percent (about €4,500) in Germany and 5 percent (€1,700) in Sweden over the first five years following a move. Women experience virtually no change in earnings in either country. Women’s share of the couple’s earnings falls by 2.5 percentage points in Germany and 1.1 points in Sweden. Women’s earnings lag in part because they spend less time working — particularly in the first year after the move when they are more likely than men to be job hunting. The gender gap persists for at least five years following a move and is largest among couples who are in their 20s. The researchers find that the birth of a child around the time of a move did not explain the widening of the earnings gap after a move.

In Germany, cultural differences between former East and West Germans can shed light on the role of gender norms. Historically, women in East Germany were more likely to work than their West German counterparts. Among German couples in which neither spouse is from East Germany, the long-run gender gap following a move is €7,000, compared to €3,100 among couples with at least one spouse of East German origin.

The researchers also study couples’ responses to one or both members losing a job in a mass layoff, one involving at least 50 workers. Using data for 2001–2006 for Germany and 1995–2007 for Sweden, they find that a man’s layoff increased the likelihood of the couple moving by about 50 percent in Germany and nearly 100 percent in Sweden. In contrast, a woman’s layoff had a negligible impact on relocation decisions in both countries.

Germany and Sweden diverge when a woman is the couple’s primary earner. In Sweden, women in these households benefit relatively more from a move than women in similar households in Germany. Even in Sweden, however, moves are of greater advantage to male than to female primary earners.

In light of their findings, the researchers conclude that “households in both countries place less weight on income earned by a woman compared to a man, particularly in Germany.”

— Steve Maas

The researchers thank the German Institute for Employment Research and the Institute for Housing and Urban Research and the Urban Lab at Uppsala University for generously providing data and support, and the Economics and Business and Public Policy Research Fund at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business for financial support.