The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and American Labor Markets

The effect of immigrants on the economy and on the jobs available to native workers has been a controversial topic throughout US history, and it continues to be so today. The Chinese Exclusion Act, which was enacted in 1882 and banned nearly all Chinese workers from immigrating to the United States, is one of the most substantial anti-immigrant initiatives. In The Impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act on the Economic Development of the Western US (NBER Working Paper 33019), Joe Long, Carlo Medici, Nancy Qian, and Marco Tabellini examine the impact of this policy on the economic development of the Western US, where most of the Chinese immigrants lived at the time.

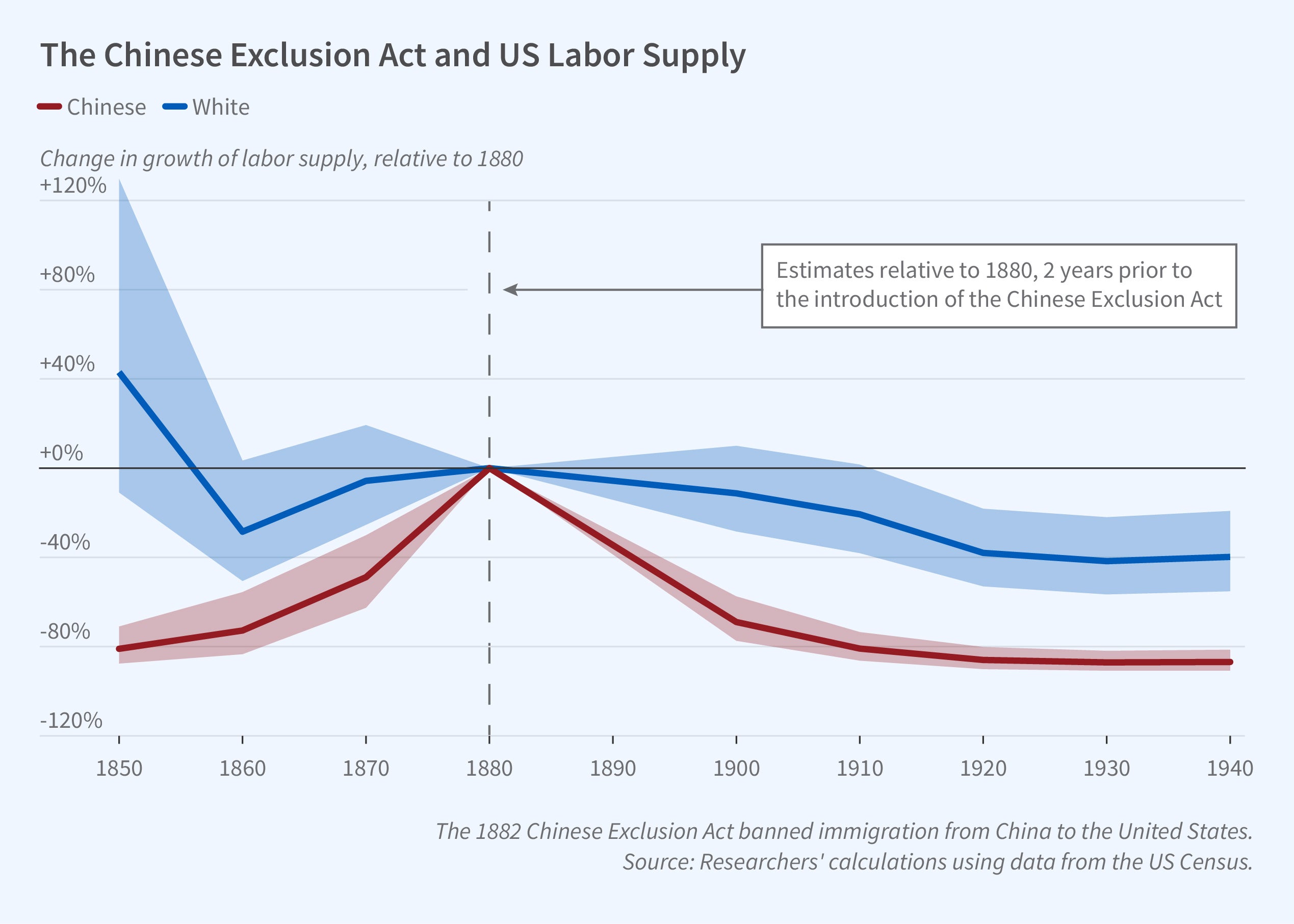

In counties where the Chinese Exclusion Act caused a large reduction in the number of workers who had emigrated from China, the number of non-Chinese male workers also declined.

In 1880, there were about 100,000 Chinese people in the United States, nearly all of whom lived in eight western states: Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming. Ninety-four percent of them were working-aged males, and they comprised 21 percent of the immigrants in the West. Concerns among native-born and European immigrant White men about Chinese immigrants suppressing wages, along with fears about cultural change, led to the passage of the Act.

The Act led to a reduction in the total labor supply of Chinese workers. Many Chinese workers left after the passage of the Act because they would not have been able to go home to visit family in China and then return to the United States, and previous laws had prevented them from bringing their wives to the United States.

Businesses opposed the Act because they did not think they would be able to replace Chinese laborers with other workers. Their view was that, in most cases, Chinese workers were not substitutes for native workers. Rather, they could be complementary, for example, if their manual labor created managerial positions for nonimmigrant workers. The researchers find evidence for this view: In counties with high levels of Chinese labor before the Act was passed, both manufacturing output and White labor supply grew more slowly than in other less-affected counties after 1882. Overall, they find that the relative decline in manufacturing output in highly affected counties was 62 percent, and the relative drop in the labor supply of White men was 28 percent. Since the population and economy of the US West at the time were expanding, the estimates obtained from the study do not reflect absolute declines in output or labor supply in affected counties but rather slower growth than in less-affected places.

Places that lost more skilled Chinese workers also experienced slower growth in the number of skilled White workers. The Act reduced the number of skilled Chinese workers by 43 percent; the researchers find a relative drop of 32 percent in the number of skilled White workers. The one group who benefited was White men born in the West who entered the mining sector when there were fewer Chinese workers. The relatively slower growth in output and labor supply was broad-based in the affected counties. It was observed across sectors both with and without high levels of Chinese labor, and lasted until at least 1940.

— Greta Gaffin