Rideshare Entry and Taxi Industry Employment

The recent rise of the gig economy has raised many new questions about labor markets and the impact of new business models on workers. In Driving the Gig Economy (NBER Working Paper 32766), Katharine G. Abraham, John C. Haltiwanger, Claire Y. Hou, Kristin Sandusky, and James Spletzer examine the effects of Uber’s rollout on the entry, employment, and earnings of workers in the taxi and limousine services (TLS) industry.

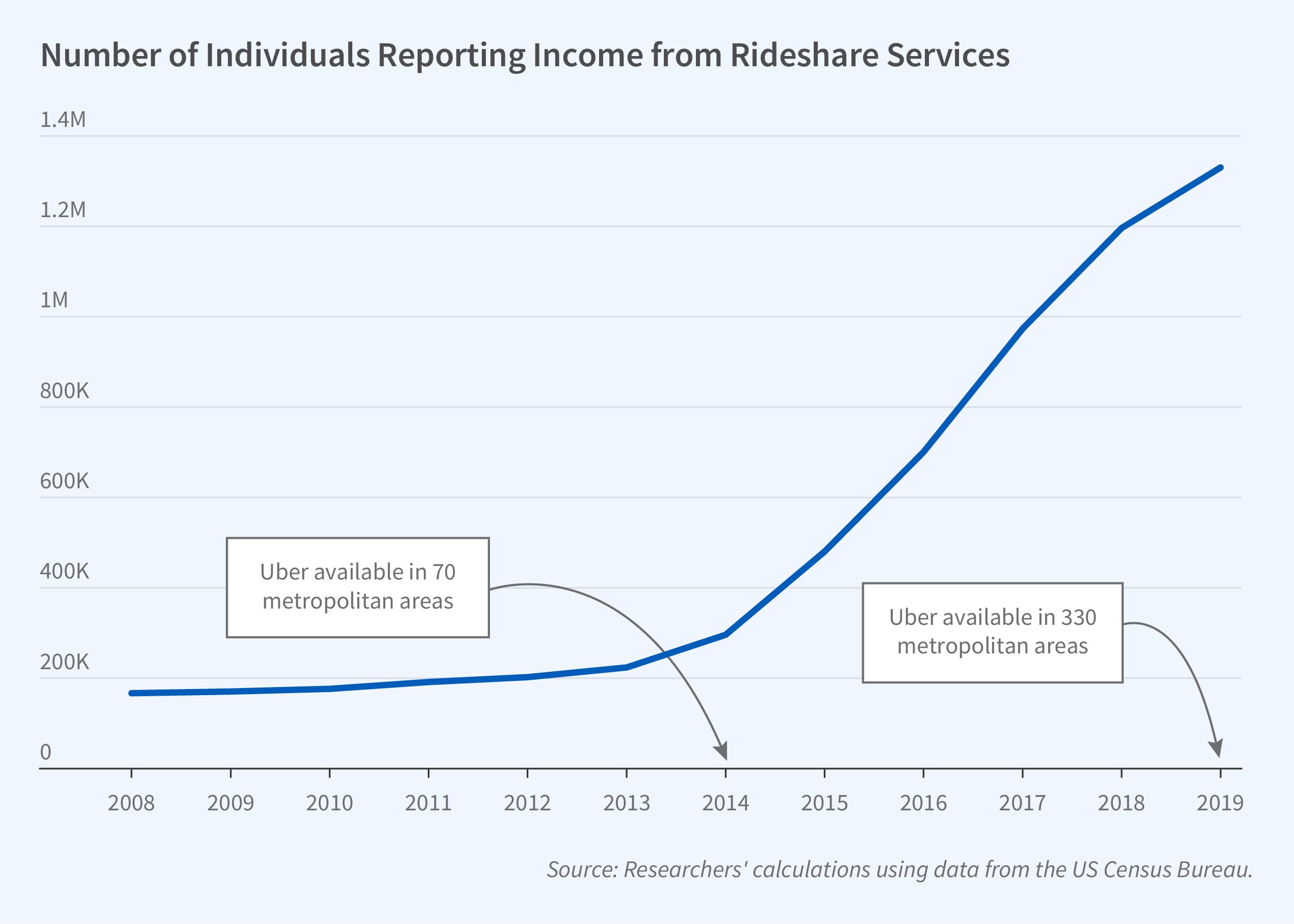

Platform work, including rideshare activities, grew rapidly in the 2010s. Uber first entered two large core-based statistical areas (CBSAs) in 2011. It then rapidly expanded, serving 330 by 2019. The number of nonemployer TLS businesses grew from just over 200,000 in 2013 to more than 680,000 in 2016 and more than 1.3 million in 2019, largely as a result of the entry of platform workers.

Ridesharing dramatically increased the pace of entry of workers into the taxi industry. New entrants were more likely to be young, female, White and US-born, and more likely to combine earnings from driving with wage and salary earnings.

The researchers link business data from the Census Bureau on nonemployer sole proprietors in the TLS industry to their wage and salary earnings from the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data as well as demographic data from the Census Bureau’s Individual Characteristics File for the years 2010–2016. They define entrants to the industry in a given year as those with nonemployer earnings in that year but not in the previous year.

The researchers compare outcomes across CBSAs where Uber entered at different times. On average, relative to the overall mean rate of entry, each additional year that Uber exists in a CBSA leads to a 65 percent increase in the likelihood that someone in that CBSA will enter the TLS industry. Recent job displacement, as measured by separation from an employer with a large quarter-over-quarter decline in employment in that year, raises the TLS entry rate by 23 percent.

Because platform work allows workers to flexibly earn income for short periods of time on their own schedules, it is an attractive option to many workers outside the taxi industry. Compared to traditional taxi drivers, new entrants are more likely to be young, female, White, and native-born, and to combine self-employment income from driving with wage and salary income.

The dramatic rise of new entrants in the TLS industry increased competition with incumbents, defined by the researchers as those with nonemployer sole proprietor earnings in 2009 and 2010. With each additional year Uber is present, the likelihood of industry exit by these incumbent workers increases and few of those who exit take other jobs. The heightened exit rate is entirely due to the behavior of low-earning (net earnings of less than $12,000 in 2015 dollars) rather than high-earning drivers. High-earning drivers are no more likely to exit after Uber’s entry than before.

There is substantial variation in the degree of local regulation of taxi markets. In CBSAs with unregulated taxi markets, high- and low-earning incumbent taxi drivers suffer annual earnings losses of $1,200 and $600, respectively, four years after Uber's entry. In more regulated markets, Uber’s entry has no effect on earnings for low-earning drivers, and the decline in earnings for high-earning drivers is only one-third as large as in unregulated markets. In New York City, which has very stringent regulations on the taxi industry, both groups of taxi drivers appear to have experienced slightly higher annual earnings following Uber’s entry.

—Whitney Zhang

Support for the project was provided by the Russell Sage Foundation under grant 1908-17672. All results have been reviewed to ensure no confidential information is disclosed (CBDRB-2018-CDAR-041, DRB-B0045-CED-20190425, CBDRB-FY22-CE0006-0023, and CBDRB-FY23-0397).