Intergenerational Gains from Educating Girls

Programs that increase educational attainment in low-income countries can yield lifelong benefits for those who attend school and also pay dividends for future generations. In Intergenerational Impacts of Secondary Education: Experimental Evidence from Ghana (NBER Working Paper 32742), Esther Duflo, Pascaline Dupas, Elizabeth Spelke, and Mark P. Walsh find that in Ghana, the children of women who received scholarships to attend high school display better outcomes both physically and cognitively. The children of men who received similar scholarships do not display such positive outcomes, however.

The researchers carried out their analysis by following up, over 15 years, on a scholarship program launched in 2008. The Ghana Education Service awarded four-year scholarships to 682 students randomly selected from a sample of 2,064 rural youth who had been admitted to a public high school but could not afford to attend.

The children of women who were randomly awarded high school scholarships in Ghana were more likely to survive to age 3 and scored higher on cognitive tests.

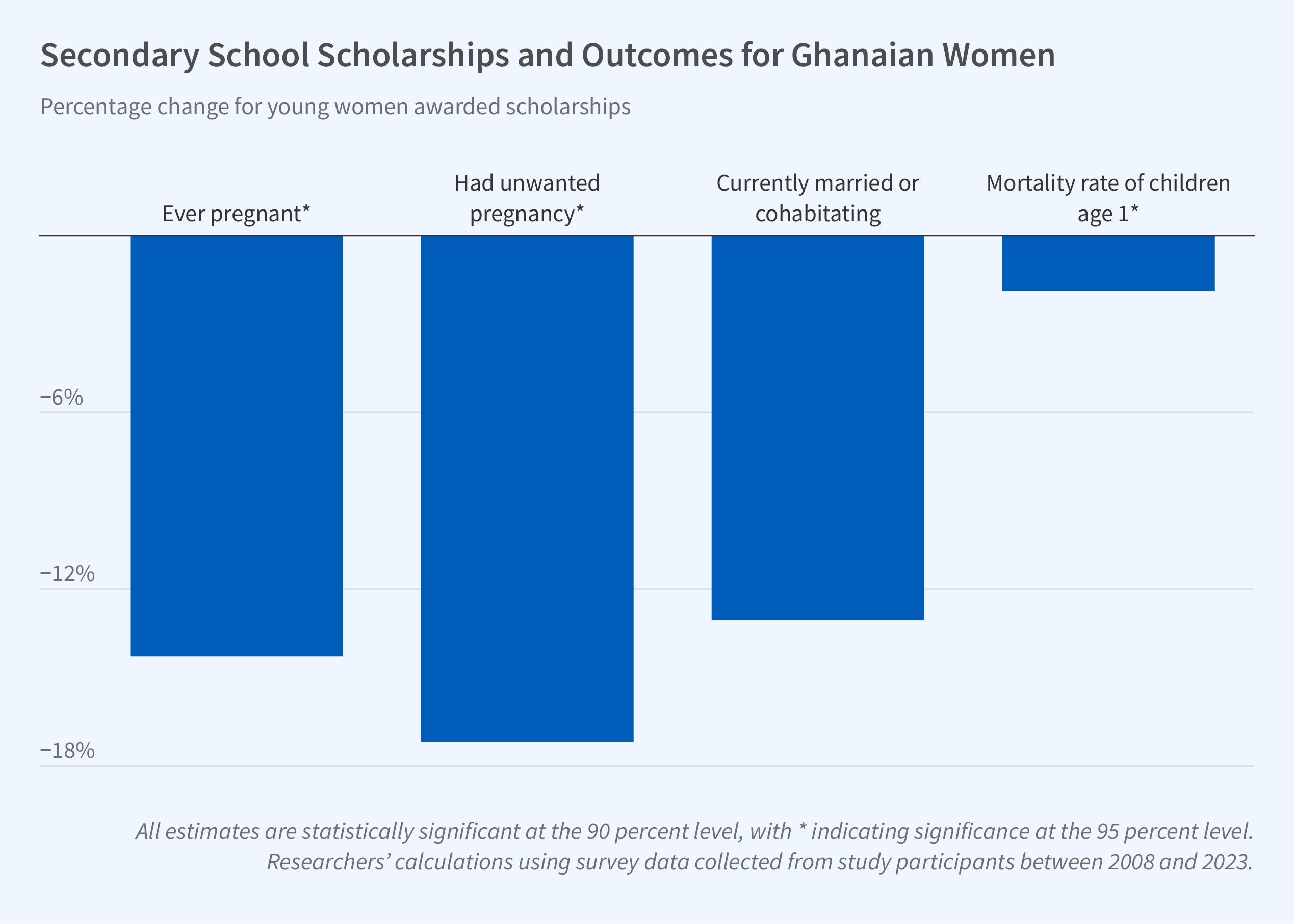

As of 2013, female scholarship recipients were 14 percent less likely to have had a pregnancy. They also had 18 percent fewer children than women who did not receive scholarships. This was driven largely by their having had 17 percent fewer unwanted pregnancies. A decade later, recipients were as likely as nonrecipients to have children, although they had slightly fewer on average. Their current or most recent partner, who generally was the father of their children, was better educated than the partners of nonrecipients.

Children of recipients were nearly twice as likely to survive beyond the age of 3, with a mortality rate of 2.2 percent compared with 4 percent among nonrecipients’ children. The researchers point out that the impact on child survival alone makes girls’ scholarships a highly cost-effective investment, costing less than $16,000 per under-3 death averted.

Over time, children of recipients increasingly outperformed those of nonrecipients on cognitive tests. Data were collected for children at intervals between 18 months and 7 years; the disparities were larger at older ages.

In contrast, the researchers found no evidence of improved outcomes among the offspring of men who received scholarships. The male recipients did not delay having children. The mortality rate of their children was no better than that of nonrecipients’ children. At ages 5 and 7, their children scored, if anything, lower than the children of nonrecipients on cognitive tests.

Why the gender difference? The researchers note that a child’s primary caregiver is, in the vast majority of cases, the mother. Male scholarship recipients were also less likely to live with their children than female recipients and less likely to have educated spouses.

Among women, scholarship recipients and nonrecipients invested similar levels of financial resources in their children, but the recipients were more attuned to preventive healthcare and more likely to engage with their children through play, singing, and basic math. The researchers conclude that “access to secondary education causes these caregivers to gain the skills to safeguard their children’s health and stimulate their children’s cognitive development.”

—Steven Maas

The funding for this study was provided by the British Academy, the JPAL Post-Primary Education Initiative, and USAID-DIV.