In the Battle against Inflation, Commitment Matters

Since World War II, the Federal Reserve’s most effective campaigns against inflation have been characterized by clear-cut goals, a willingness to accept higher unemployment, and a refusal to give up prematurely.

In Lessons from History for Successful Disinflation (NBER Working Paper 32666), Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer study nine attempts by the Federal Reserve between 1946 and 2016 to put the brakes on inflation. They investigate what made some efforts more successful than others.

In all nine episodes, policymakers declared the current rate of inflation was unacceptably high and initiated contractionary policies that they acknowledged could dampen economic growth.

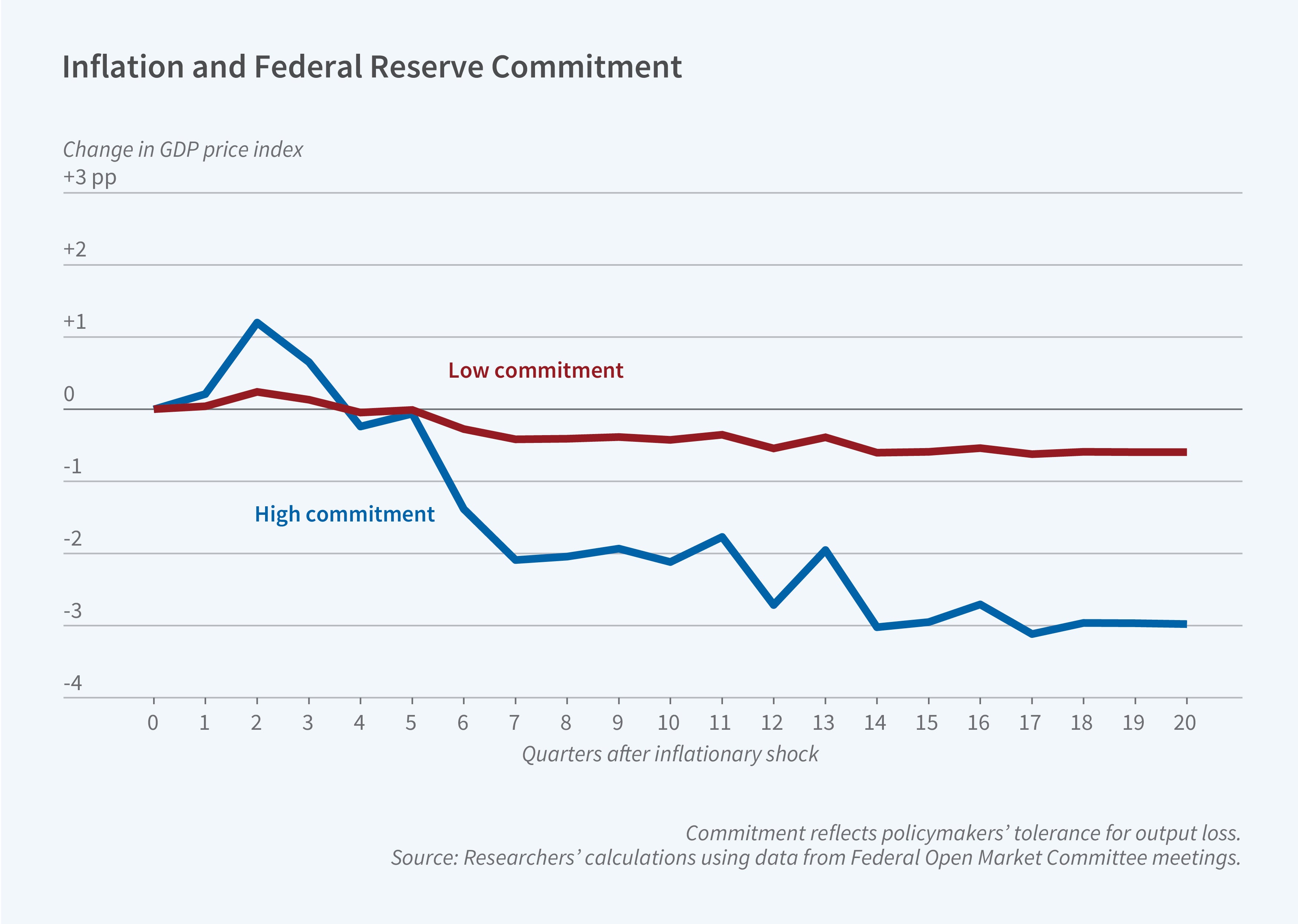

Since 1946, inflation fell on average by 2.5 percentage points more when monetary policymakers were highly committed to restoring price stability than when they were less committed.

After five years, inflation had declined on average by 3 percentage points when policymakers were most committed to the fight and by only a half percentage point when they were least committed.

After combing through transcripts of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meetings and public statements and testimony of Fed members, the researchers define periods of strong commitment as those when policymakers expressed willingness to accept steep costs in reduced economic output, clearly stated their objectives, displayed confidence in the singular importance of monetary policy in fighting inflation, and redoubled deflationary efforts when they had let up on the brakes too soon.

The researchers cite May 1981 as an episode that exemplified renewal of resolve. “Through the course of recent history at least, we’ve backed off and we’ve made a mistake each time,” said one FOMC member according to transcripts of the FOMC meeting. Further, the Federal Reserve Board took a “whatever it takes” stance: “I think it’s more likely that after a protracted period of these high real interest rate levels we will see a significant recession both here and abroad,” said Anthony Solomon, vice chair of the FOMC. Federal Reserve Board Chair Paul Volcker stressed the board’s “indispensable role” in fighting inflation: “To be effective, we must demonstrate that our own commitment is strong, visible, and sustained.” The result was a drop in inflation as measured by the core Personal Consumption Expenditures price index, a measure that excludes food and energy, from around 9 percent in 1980 to around 4 percent in 1984. By comparison, a low-commitment episode in 1968 saw inflation remain at over 4 percent for the next three years.

The researchers found that high or medium commitment was more likely to result in the complete achievement of goals, while inflation targets were abandoned in all low-commitment episodes.

As reasons for monetary policymakers prematurely curtailing their efforts, the researchers cite unacceptable economic costs, belief that monetary policy had done its part and it was up to others to do the rest, and fear that fiscal policymakers would counter their efforts and set the stage for higher inflation in the long run.

The latest disinflationary effort, launched in July 2022, is shaping up to be the tenth postwar deflationary episode. The researchers conclude that it reflects key traits of strong commitment. Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly expressed a goal of bringing inflation down to 2 percent and asserted that the Federal Reserve bears the ultimate responsibility for doing so. The researchers conclude, “…based on history, the most likely outcome of today’s attempt at disinflation is that monetary policymakers will persevere in their disinflationary efforts until they have brought inflation down to, or very close to, their long-run target.”

—Steven Maas

This paper was prepared for the NBER conference on Inflation in the COVID Era and Beyond supported by the Smith Richardson Foundation.