Financial Incentives Can Increase Permanence for Foster Children

Protracted periods in foster care can lead to negative long-term outcomes for children. Many states have tried to shorten foster care stays by moving children into either permanent adoptive homes or kinship care. While foster parents receive financial support for the children in their care, adoptive parents or kin guardians often receive less — or no — support. In Financial Incentives for Adoption and Kin Guardianship Improve Achievement for Foster Children (NBER Working Paper 32560), David Simon, Aaron Sojourner, Jon Pedersen, and Heidi Ombisa Skallet examine the outcomes of a policy reform in Minnesota that increased payments to adoptive parents and kin guardians of children over the age of six.

Over a tenth, and sometimes as much as a quarter, of children in foster care remain in it until they become adults, and the older a child is, the less likely they are to exit the system through either adoption or placement with a kin guardian. Children who “age out” of foster care are more likely to have a difficult transition into adulthood, and they have an increased risk of homelessness.

After a reform in Minnesota, children over age six spent an average of five fewer months in foster care.

Kinship care — placing a child with relatives or fictive kin such as family friends — is an alternative to adoption and long-term foster care placement. While kin guardians have a stronger interest in the child, they may not be able to support the child financially over the long term.

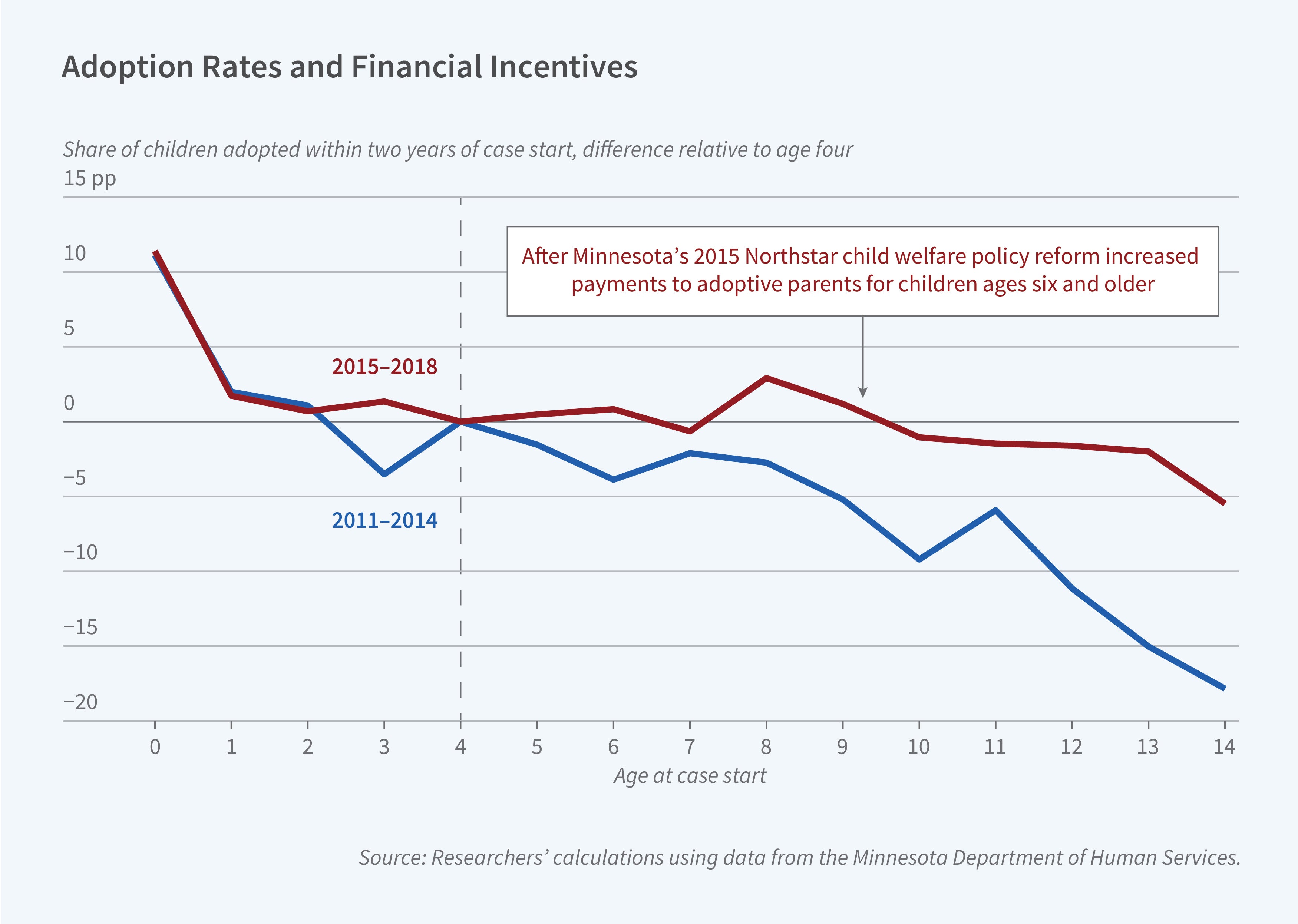

In January 2015, the State of Minnesota adopted a new policy that led to adoptive parents or kin guardians receiving average monthly payments of 90 percent of what foster parents receive to care for children over the age of six, up from 21 percent before the policy change, but caused little change among guardians of children under age six. This reform resulted in average monthly payments of $128 more for adoptive parents and $362 more for kin guardians of older children than of younger children. After this reform, children over the age of six spent an average of five fewer months in foster care before achieving permanency through adoption or kin guardianship.

The researchers find that children affected by this reform had a boost in academic achievement of between a third and a half of a standard deviation after three years. Before the policy, these children received an average score that was 0.77 standard deviations below the average score for the whole state population. Additionally, the authors document that adopted foster children have fewer suspensions and are less likely to change schools in the 1–3 years leading up to when test scores are measured. The researchers estimate that this learning improvement translates into a rise of about $32,000 in the expected net present value of a child’s lifelong earnings.

—Greta Gaffin

Researchers acknowledge funding from the University of Connecticut Health Economics and Policy Education Lab, and from Casey Family Programs.