Tracking the Impact of Short-Term Rental Regulation

The rapidly expanding home-sharing market has led to calls for new regulations to restrict activity in short-term rental (STR) markets. Debates about such regulations have identified potential benefits of an active STR market as well as potential costs. In The Effects of Short-Term Rental Regulation: Insights from Chicago (NBER Working Paper 32537), Ginger Zhe Jin, Liad Wagman, and Mengyi Zhong present a novel analysis of local regulation of an STR market.

The researchers study Chicago because it was one of the first large US cities to attempt to regulate STR activities in a comprehensive way. The city’s STR ordinance aims to permit such rentals while addressing public safety, consumer protection, and affordable housing concerns. In particular, it requires hosts to register, follow strict guidelines, and heed locality-specific STR restrictions based on the varying needs of different communities. This approach differs from that of other large cities, such as New York City, which have adopted regulations that attempt to ban STR activities and that can be very difficult to enforce. Chicago’s STR regulation also coincides with the adoption of a new 4 percent tax on STRs on top of the city’s existing 17.4 percent hotel accommodation tax.

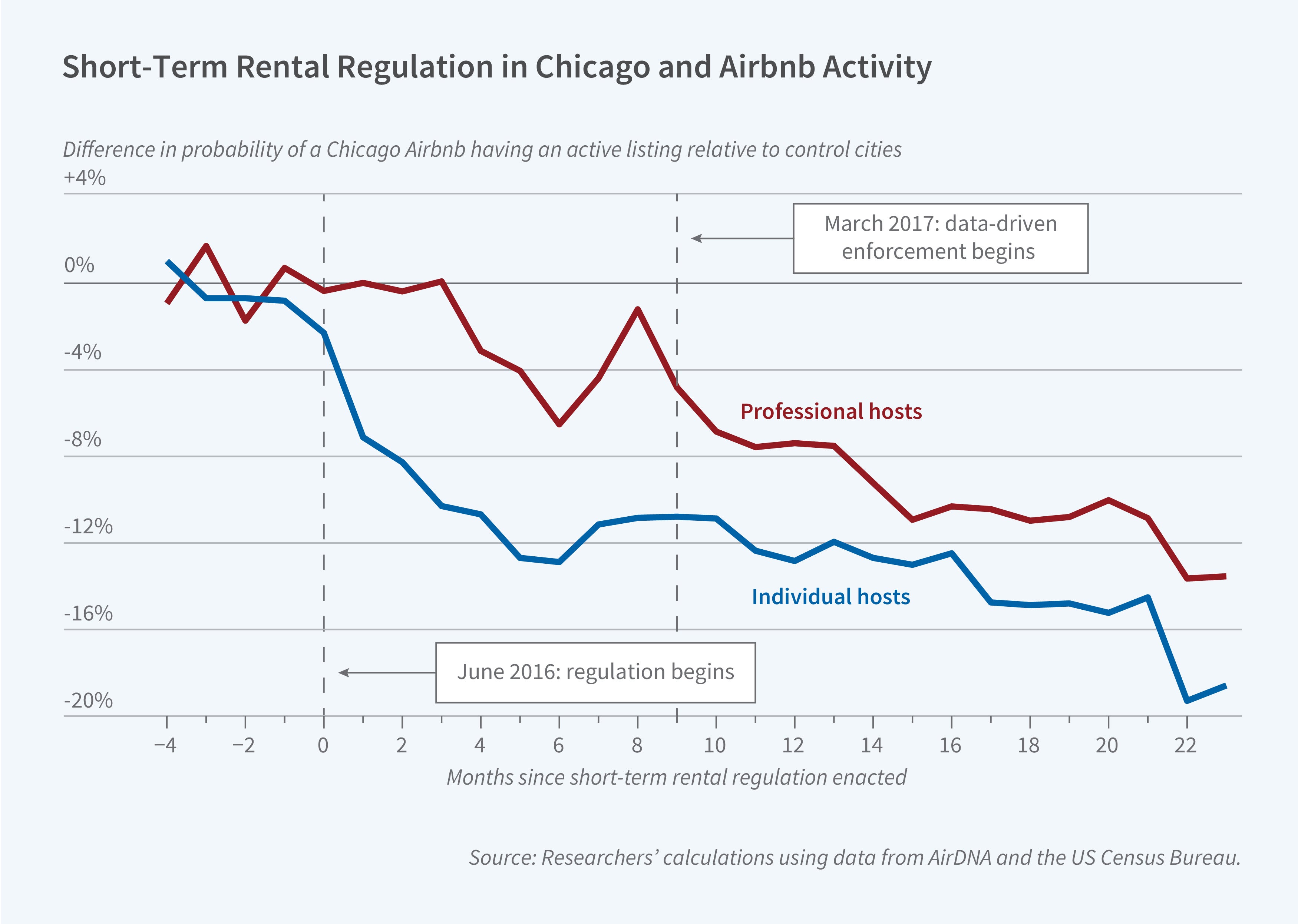

When short-term rental regulations were introduced in Chicago, Airbnb listings fell by 16 percent.

By comparing Airbnb listings in Chicago with those in three other large US cities from January 2016 to May 2018, the researchers estimate that the new regulation led to a 16.4 percent decline in the total number of active listings. The decline was only significant after regulators began receiving detailed data feeds on STR listings directly from platforms that facilitate this market. The drop in listings was driven by both a higher rate of exit by existing listings and a decline in the arrival rate of new listings. The researchers do not find any effect of the enactment or enforcement of Chicago’s citywide STR regulation on the average before-tax price of an Airbnb listing or on the number of reservations per active Airbnb listing.

The researchers study a range of other consequences of the STR regulation and find localized reductions in burglaries near buildings that prohibit STR listings as well as declining Airbnb revenues in areas with above-median hotel revenues. They highlight the important role that platform data feeds play in the enforcement of STR regulations, particularly with respect to professional hosts.

—Lauri Scherer

The researchers are grateful to AirDNA and Smith Travel Research for providing the data, and to our home universities as well as the Illinois Institute of Technology (Wagman’s former employer while we conducted part of the research) for financial support.