Returns to School Spending on Black Students

New evidence from a study of a school spending equalization program adopted by Mississippi in 1920 reveals the extent to which segregation disproportionately benefited White students. In School Equalization in the Shadow of Jim Crow: Causes and Consequences of Resource Disparity in Mississippi circa 1940 (NBER Working Paper 32496), David Card, Leah Clark, Ciprian Domnisoru, and Lowell Taylor analyze racial disparities in per-student spending during the interwar years.

Prior to the launch of the equalization program, schools were funded by local property taxes and per capita state grants based on the number of people aged 5 to 21 in a district. With Black students disenfranchised and attending segregated schools, local decision-makers disproportionately funded White schools. Indeed, the researchers write that “the per capita grant system converted local Black children into a resource for white schools”; local officials may have even exaggerated the number of Black students. As a result of the state grants, White students in predominantly Black districts enjoyed greater per capita funding than their counterparts in predominantly White districts. The equalization program was created to address that disparity.

Modest increases in educational spending on Black students would have substantially improved their educational attainment and lifetime income.

Counties in the Mississippi Delta region were excluded from additional aid because existing funding was considered sufficient — at least for White students. About half of the state’s Black residents lived in that region. The equalization program increased school spending for Black students in other parts of the state. The researchers use this change in per-student spending to analyze the link between school funding and later-life outcomes for Black students. The equalization program came with strings attached that encouraged participating districts to raise their property taxes and increase attendance rates, including those of Black students.

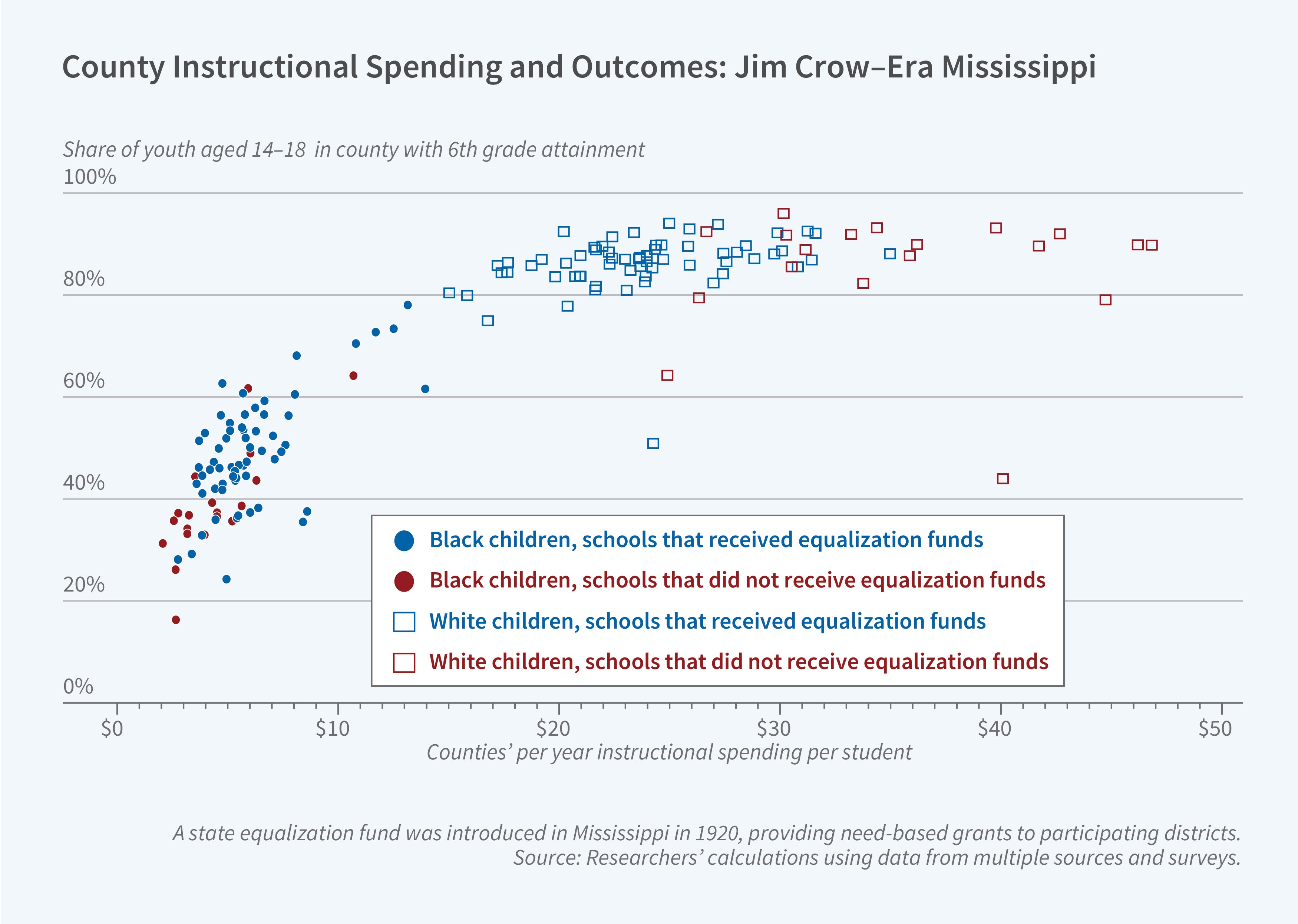

Using 1940 census data, the researchers estimate the impact of a $1 increase in annual educational spending per Black student from a base of $5 per year. They find that the fraction of students completing at least the sixth grade increased by 1.5 percentage points from a base of 45 percent. Extrapolating from the sample, they estimate that Black students would have completed two more years of education had districts spent the same on them as they had on Whites, $25 per year. Even greater potential gains emerge from comparisons of Black youth in equalization counties with their peers in otherwise similar bordering counties that did not participate in the program.

Additional educational spending had a lifelong impact. The researchers compare outcomes of matched respondents in the 1940 and 2000 censuses and find, in a sample of about 6,000 individuals, that a $1 increase in per capita spending on Black students in 1940 was associated with a 3 percent increase in family income in 2000.

The study finds that the equalization program had a negligible effect on the educational attainment of Whites. Given the wide racial disparity in spending, the researchers conclude that reallocating dollars between the races could have dramatically improved outcomes for Black students at little cost to White achievement.

—Steve Maas

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.