The Costs of Sovereign Debt Crises

Sovereign debt crises have been a recurring phenomenon in the global economy for over two centuries, with far-reaching consequences for both creditors and debtor nations. Two recent studies examine creditor losses as well as the often-overlooked social costs of sovereign defaults.

In Sovereign Haircuts: 200 Years of Creditor Losses (NBER Working Paper 32599), Clemens M. Graf von Luckner, Josefin Meyer, Carmen M. Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch analyze creditor losses in 327 restructurings across 205 default spells since 1815. In each case, they calculate total creditor losses — “haircuts” — across all restructurings within the same default spell.

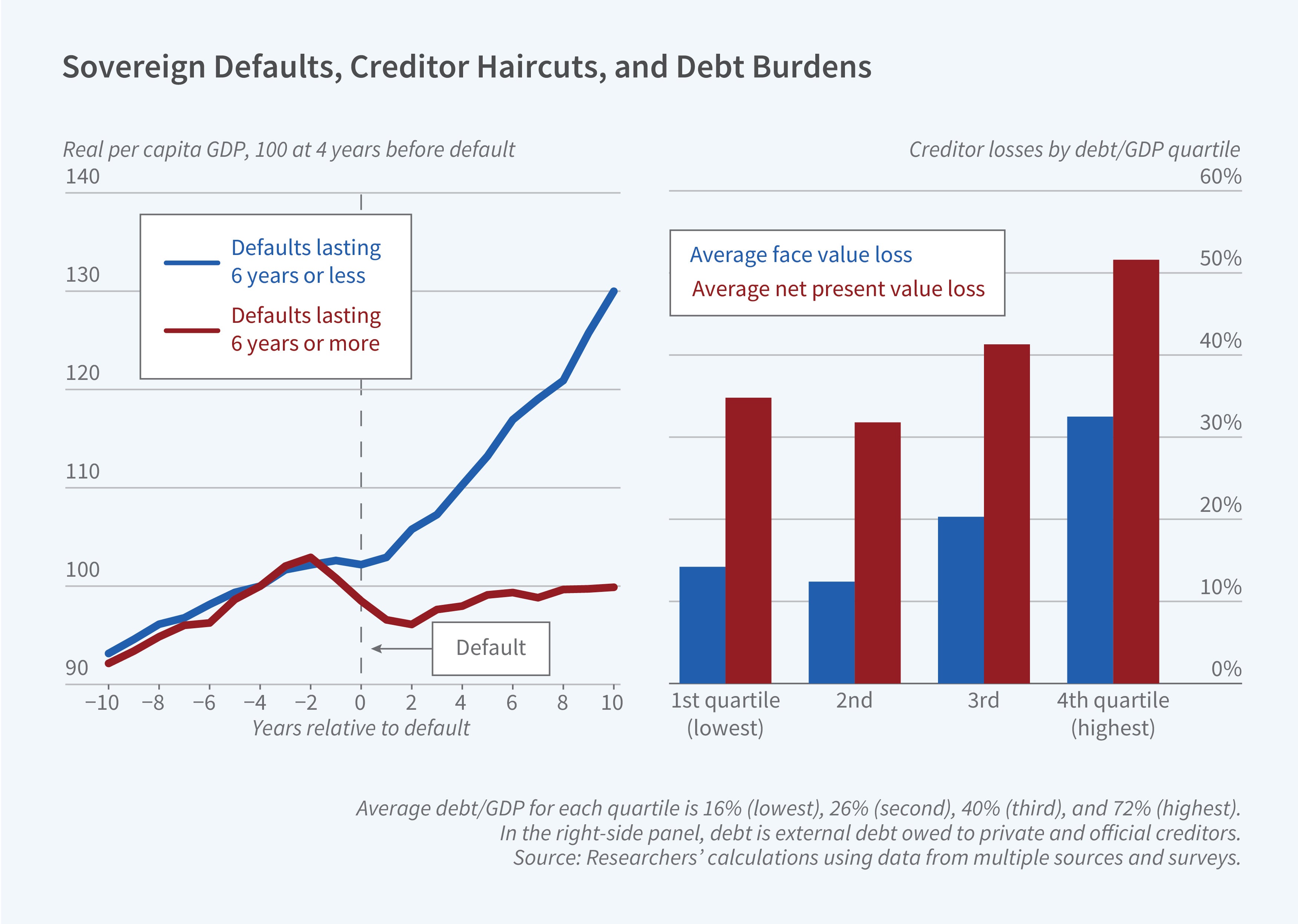

Creditor losses vary widely and in some cases are total, but they have averaged around 45 percent for over two centuries, despite significant changes in the global financial system. Poorer countries, first-time debt issuers, and those with heavy external borrowing face larger losses, on average, when they default.

Sovereign defaults have long-lasting economic and social costs for defaulting nations.

Geopolitical shocks such as wars, revolutions, or the breakup of empires often lead to the deepest haircuts. Longer debt crises typically result in larger creditor losses, while interim restructurings often provide limited debt relief. The researchers caution that creditor losses do not always translate directly into debt relief for the borrowing country, since a restructuring may address only a portion of a nation’s total debt.

Building on these findings, The Social Costs of Sovereign Default (NBER Working Paper 32600) by Juan P. Farah-Yacoub, Clemens M. Graf von Luckner, and Carmen M. Reinhart shifts the focus to the economic and social consequences of sovereign defaults. This study analyzes 221 default episodes from 1815 to 2020. Within three years of default, affected economies’ real per capita GDP falls behind that of nondefaulting countries by 8.5 percent, and after a decade, the gap is 20 percent. Longer defaults result in worse economic and social outcomes.

Ten years after a default, 10 percent more households in the defaulting nation are living in poverty compared to nondefaulting nations. The infant death rate is higher by 5 per 1,000, and life expectancy at birth is 1.1 years lower. The researchers cannot determine whether default-induced recessions have a larger impact on these social measures than recessions with other causes.

—Leonardo Vasquez