Investment Effects of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 was the most significant reform to corporate taxation in the US in nearly four decades. It reduced the top corporate income tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, increased investment incentives by making equipment investment fully tax-deductible, and changed the tax treatment of US businesses’ overseas income. The various changes in tax rules affected different firms in different ways, creating cross-firm heterogeneity in the net effect on investment incentives. In Tax Policy and Investment in a Global Economy (NBER Working Paper 32180), Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Matthew Smith, Owen Zidar, and Eric Zwick use firm-level data on tax returns to study how the legislation affected both the domestic and foreign investment of US firms.

The researchers analyze tax return data on C corporations headquartered in the US for the period 2011–2019. This means that they are studying investment responses in the first two years after the tax reform. Different firms had different exposure to the reforms embodied in the TCJA because of differences in their taxable income and the level and composition of their investment spending. For example, since the TCJA increased the incentives to invest in equipment more than it increased the incentives to invest in structures, the researchers treat firms that historically invested more on equipment than structures as receiving a larger boost to investment incentives. Similarly, the reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate did increase incentives for tax-paying firms, but the increase was smaller for firms that were not paying taxes at the time because of low levels of taxable income or because of other tax credits they got prior to the reform.

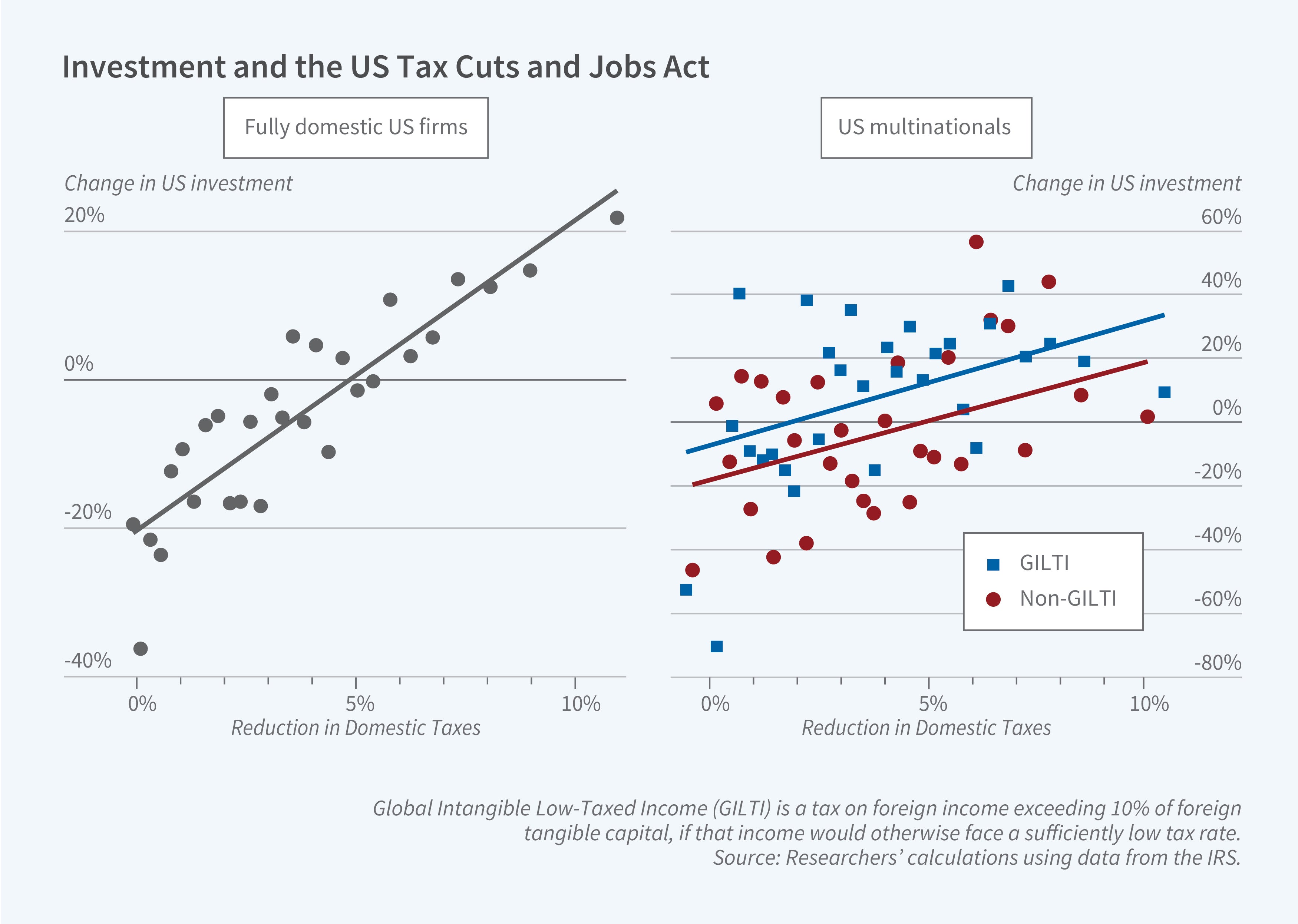

The researchers exploit the cross-firm variation to estimate the responsiveness of corporate investment to key features of the tax reform. They compare firms for which the net-of-tax cost of new domestic investment changed by more and by less after 2017, as well as firms with larger and smaller changes in the cost of foreign capital investments, and larger and smaller changes in their marginal tax rate on earnings. They document significant declines in the average net cost of new investment, both for investments in the US and for investments abroad. They estimate that a 1 percent decline in the effective cost of new domestic capital goods raises domestic investment spending by about 3 percent, and a 1 percent decline in the cost of foreign capital investment also has a positive effect of about 0.6 percent. A 1 percent increase in the after-tax value of a dollar of taxable income is associated with an increase in investment of about 3.8 percent. To summarize these different effects, the researchers report that the TCJA increased domestic investment in the short run by about 20 percent for a firm with an average-sized tax shock versus a no reform baseline. The estimated domestic investment increase is larger for multinational firms that also benefited from the foreign investment incentives in the TCJA, suggesting complementarity between domestic and foreign capital.

The researchers note that they have only two years of post-TCJA data with which to estimate the law’s effect on firm investment, and the law’s impact on corporate tax revenues will depend on its longer-run impact on the corporate capital stock and on wages. In addition, if all firms in the economy move to increase investment at the same time, crowding out at the macroeconomic level will offset the relative increase they observe in the data. To address this issue, they use their estimated short-run effects to calibrate a model of long-term capital investment and wage determination. They predict a long-run capital stock increase of 7.2 percent and a 0.9 percent increase in wages after 15 years.

When it was enacted, the TCJA was estimated to reduce corporate tax revenues by between $100 and $150 billion per year over the 2018–2027 period. The researchers find that the increased investment and wages resulting from the law have very limited effects on receipts from the corporate income tax or other revenue sources, such as the payroll tax and income tax. They conclude that such indirect effects do not substantially offset the decline in domestic corporate tax revenue of about 40 percent over the 10-year budget window.

—Shakked Noy

The researchers acknowledge support from the Ferrante Fund, the Chae fund at Harvard University, the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago and NSF support under grant no. 1752431.