Improved Market Access Helps the Fishermen of Remote Amazonia

A community-financed program to procure boats, ice, and fuel enabled impoverished communities to avoid middlemen in trade, boosting incomes and increasing food consumption.

In the impoverished communities of the Brazilian Amazon, one of the most remote settings in the world, fishermen harvest a huge, prehistoric, air-breathing fish called a pirarucu. Historically, they have sold the fish to middlemen who wield significant market power, resulting in a large gap between the price the fishermen receive and the price charged to the consumer.

In Big Fish in Thin Markets: Competing with the Middlemen to Increase Market Access in the Amazon (NBER Working Paper 29221) Viva Ona Bartkus, Wyatt Brooks, Joseph P. Kaboski, and Carolyn E. Pelnik study an intervention that enabled communities to bring the fish to market directly and thereby increased incomes as much as 27 percent.

Fishing for pirarucu is straightforward: the fish must come to the surface to breathe, at which point they are harpooned. But because the fish are perishable, delivering them to market is a challenge. Prior to the intervention, direct access to the final market involved multiday ferry rides to Manaus, the capital city of Amazonas. Instead of making this journey, most fishermen sold to middlemen who have boats that permit faster delivery. The middlemen, part of a cartelized supply chain, brought the catch to outside markets. The intervention, initiated by a nongovernmental organization, involved community-financed procurement of boats, ice, and fuel to enable fishermen to cut out the middlemen.

Fundação Amazonas Sustentável (FAS) — the leading nongovernmental environmental organization in Brazil — focuses on sustainable economic development of both the Amazon’s natural resources and its river communities. FAS’s Bolsa Floresta program, Bradesco Bank, and the state of Amazonas pay a monthly subsidy to households in river communities who promise to care for the forest. Communities that choose to participate in the boat-buying effort forego their Bolsa Floresta payments for the period of time needed to pay for a boat, approximately three years.

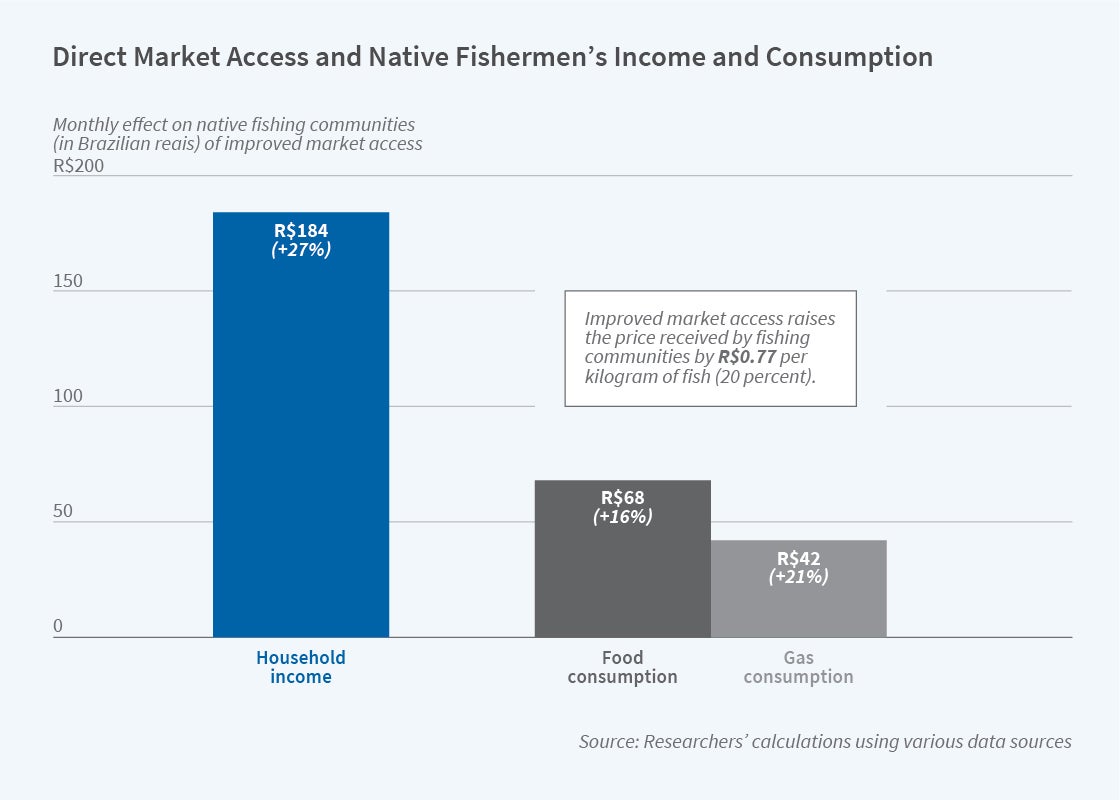

In evaluating the intervention, the researchers find that income in boat-acquiring communities rose by 27 percent relative to income in the control communities. The intervention also raised consumption, including food expenditures. They did not find a significant increase in fishing, notable in a situation where overfishing could plausibly be a concern. Rather, they found an increase in the price fishermen received for the fish.

The researchers find that boat investments are cost effective: boats can be paid for in under three years, well within the lifespan of the typical boat. They also find that, in the first year of the intervention, communities continued to sell to middlemen, but they may have earned a higher price when doing so. This may have reflected a risk-mitigation strategy, as communities continue to sell a substantial portion of their pirarucu to known buyers while also organizing their own boats.

The researchers explored why, if the intervention was cost effective, community members had not implemented such a strategy on their own. They suggest that the lack of a boat constituted a poverty trap, especially in the presence of a cartel with market power in pricing. Middlemen were capable of financing the large fixed cost of a boat, but poor communities were not. Market power enabled the middlemen to pay below-market prices for fish, thus creating a poverty trap even though the natural cost structure did not make this an inevitable outcome.

— Lauri Scherer