Misperceptions of the Social Security Earnings Test and the Actuarial Adjustment

The Social Security Retirement Earnings Test (RET) applies to people before the full retirement age (FRA), which is age 67 for those turning 62 in 2022 and beyond. For individuals who claim retired worker benefits before the FRA, Social Security withholds benefits if earnings exceed a certain exempt amount. In 2021, the exempt amount is $18,960, although a higher amount applies in the year of attaining the FRA. Benefits are withheld at a rate of $1 for each $2 in earnings above the lower exempt amount. Upon reaching the FRA, benefits are increased by five-ninths of 1 percent for every month that benefits were withheld due to the RET.

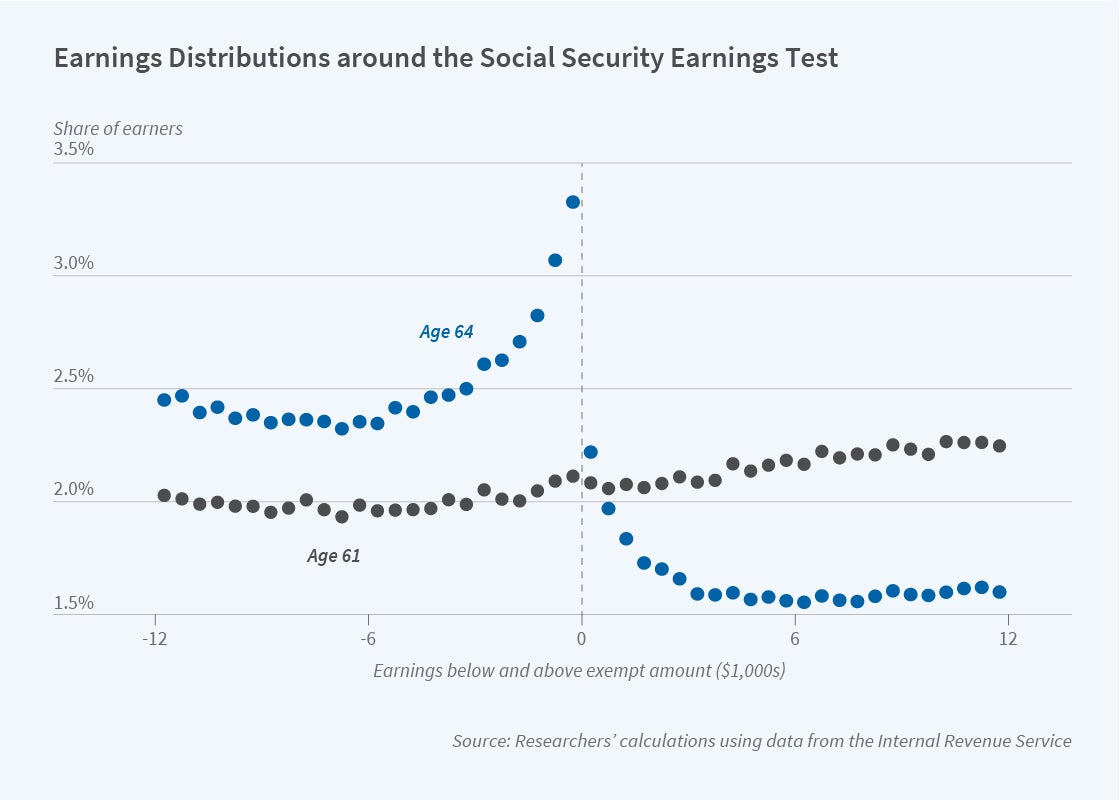

Researchers have long been aware of disproportionate “bunching” of earnings just below the RET exempt amount. The exempt limit creates a “kink” in the incentive to earn income, in that earnings above the limit are subject to withholding, which may lead to left-bunching just below the exempt amount. On the other hand, the post-FRA adjustment of benefits creates a “notch,” in that earnings just above the exempt amount trigger a later benefit increase. This feature, if understood properly, dulls the incentive to left-bunch and could lead to right-bunching just above the exempt amount.

Why do earnings respond strongly to the RET despite the actuarial adjustment of benefits to compensate for benefit withholding? In Misperceptions of the Social Security Earnings Test and the Actuarial Adjustment: Implications for Labor Force Participation and Earnings (NBER RDRC Working Paper NB20-09), researchers Alexander Gelber, Damon Jones, Ithai Lurie, and Daniel Sacks provide new evidence on this question.

The authors use earnings data from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for 53 million people born between 1939 and 1953 at ages 60 to 64. The primary earnings measure is total W2 income, as reported across all employers. This is supplemented with data on self-employment earnings as reported on Schedule SE.

The authors explore several classes of explanations for left-bunching. First, they examine “standard” explanations – for example, that the earnings distribution is downward-sloping, creating more mass to the left than to the right of any point on the earnings distribution, or that bunching is driven by small or lumpy adjustments. However, the evidence is inconsistent with these explanations. The earnings distribution is nearly flat. Using age 61 earnings as a measure of pre-RET earnings, the authors find that left bunchers overwhelmingly come from far above the exempt amount, suggesting that these are not small or lumpy adjustments. Bunching is also highly asymmetric, with an excess mass of earners just below the exempt amount and much less mass further below this amount.

Next, the authors turn to two other possible explanations. The first is “spotlighting,” in which individuals misperceive the RET as applying to all earnings once earnings exceed the exempt limit and not only to earnings beyond the limit. The second is that a behavioral bias such as loss aversion leads individuals to react strongly to even a modest reduction in benefits. They note that the key to distinguishing between these explanations is to examine the employment response to the RET incentives, as the RET would affect the decision to work under spotlighting but not under loss aversion. Comparing individuals with age-61 earnings just above and below the exempt amount, the authors find a small but statistically significantly greater decrease in employment by age 64 among those just above the limit, which they take as evidence that at least some people misperceive their incentives under the RET.

The authors note that their findings have two key implications. First, the misperception of the RET is costly to beneficiaries, in that those who locate just below the exempt amount are leaving substantial “money on the table” by not receiving the post-FRA increase in benefits they would be eligible for if they had earned just above this amount. Second, analyses of left-bunching in the context of the RET and other tax and transfer programs have been used to estimate individuals’ labor supply response to changes in the return to work. To the extent that behavior reflects a misperception of incentives rather than a response to the actual incentives, caution may be warranted in using such estimates as a measure of the labor supply response to changes in the incentive to work.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant #RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of NBER, SSA or any agency of the Federal Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.