Health Inequality and Economic Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender

In Health Inequality and Economic Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender (NBER Working Paper 32971 an earlier version, NBER RDRC Paper NB23-11), Nicolò Russo, Rory McGee, Mariacristina De Nardi, Margherita Borella, and Ross Abram use data from the Health and Retirement Study over the period 1996–2018 to evaluate measures of health inequality in middle age and the consequences of such health disparities.

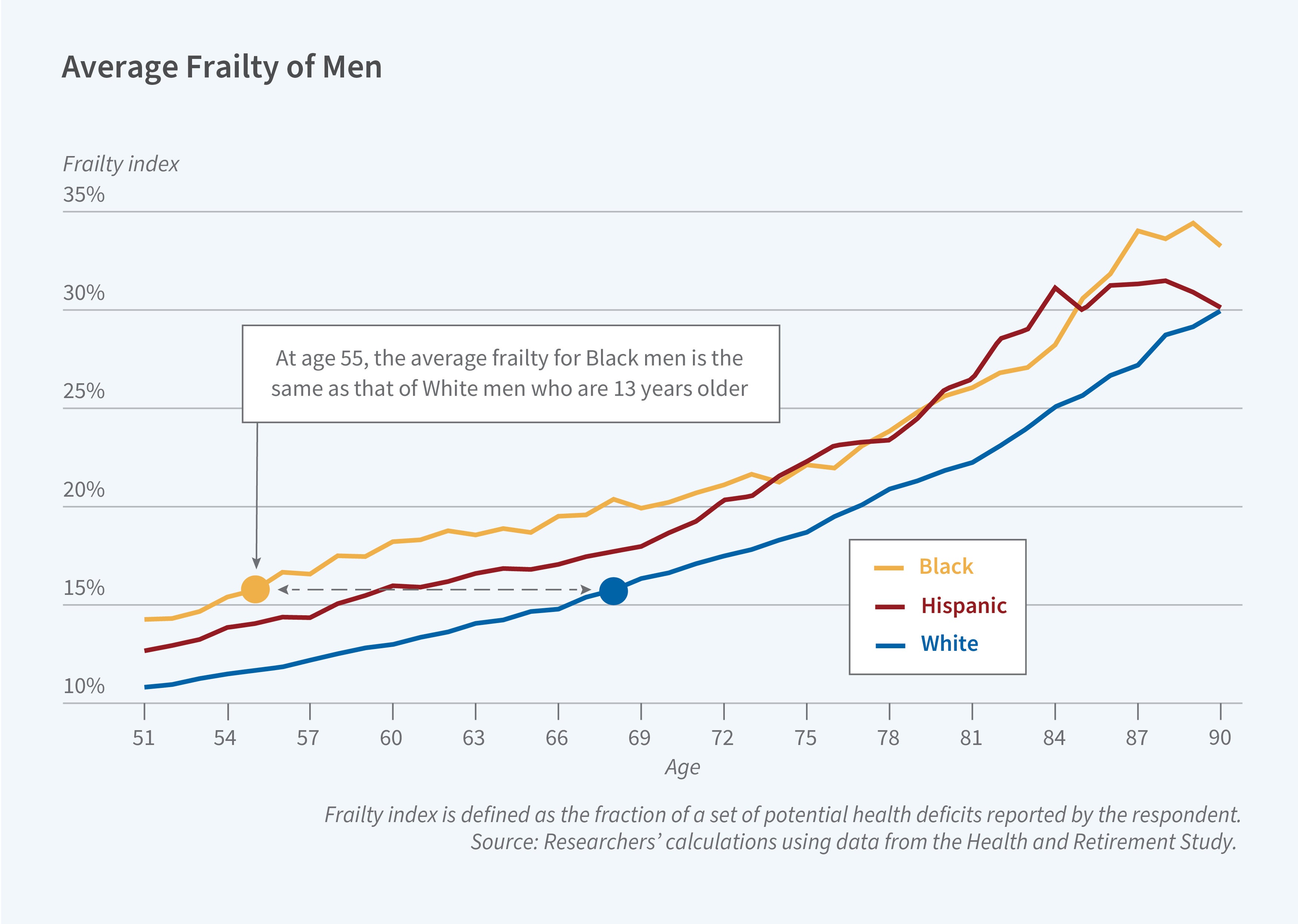

At age 55, Black men and women have the same “frailty,” a measure of health status, of White men and women 13 and 20 years older, respectively.

They consider two health measures: self-reported health status, measured by the response to a survey question that asks individuals to rate their health as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor, and “frailty,” which is defined as the number of health deficits an individual reports as a fraction of a universe of potential health deficits. These health deficits include medical conditions, such as diabetes and cancer diagnoses, as well as difficulties with daily living activities such as eating, paying bills, walking up stairs, and healthcare utilization. They find that while both measures of health are highly predictive of key economic outcomes, frailty is marginally more so. It also has the advantage of offering a quantitative interpretation.

Using frailty to measure health inequality by race, ethnicity, and gender, the researchers report three findings. First, there is substantial health inequality by race, ethnicity, and gender. At age 55, Black men and women have frailty levels, which could be viewed as “biological age,” comparable to those of White men and women 13 and 20 years older, respectively. Hispanic men and women exhibit frailty levels similar to those of White men and women 5 and 6 years older, respectively.

Second, most of the specific health deficits that together make up frailty are more prevalent among Black and Hispanic than White individuals, with the exception of deficits that require a medical diagnosis. The researchers impute medical diagnoses for Black and Hispanic individuals and conclude that there may be significant underdiagnosis, particularly among Black men. The most underreported deficit relative to their imputations is lung disease, while the least underreported is high blood pressure. The researchers compute a measure of “potential frailty” that accounts for potential underreporting and it suggests even larger gaps than the frailty measures based on actual reports. At age 55, Black men have the potential frailty of White men 21 years older, and Black women have the potential frailty of White women 25 years older.

Third, frailty at age 55 is a powerful determinant of health and economic inequality later in life. If Black individuals at age 55 had the health of their White peers, the life expectancy gap between these two groups would halve, and the gap in disability duration would decrease by more than 40 percent. These findings suggest that targeted health interventions for minority groups before middle age could substantially reduce disparities in the length and quality of life at older ages.

— Greta Gaffin

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA), funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. Borella gratefully acknowledges funding from the European Union - Next Generation EU, Mission 4 Component 2, within the NRRP (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) project “Age-It - Ageing well in an ageing society” (PE0000015 - CUP H73C22000900006).

The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, NBER, CEPR, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, the Federal Reserve System, the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.