Challenges of Disability Applications and Appeals among LA’s Homeless

In Barriers Faced by People Experiencing Homelessness in Los Angeles When Filing Social Security Disability Appeals: A Qualitative and Community-Engaged Study (NBER RDC Paper NB23-21), Alex Sizemore, Jordy D. Coutin, and Philip Armour find that for people experiencing homelessness (PEH), appealing a denial of disability benefits from the Social Security Administration (SSA) can be overwhelming. Using interviews with PEH and service providers as well as guidance from a community advisory board, the researchers report that people who are unhoused often struggle to stay in contact with their SSA representatives and others who can help them, receive lower quality healthcare, endure significant confusion and frustration when navigating the bureaucracy, and face substantial delays in receiving benefits.

People experiencing homelessness are approved for SSA benefits at half the rate of the housed population.

Many claimants have to wait more than two years for their appeal to be resolved. The longer the wait, the more likely a person who is unhoused will experience serious declines in health and food security. Of the 13 PEH interviewed, two reported engaging in incoming-generating illegal activities to stay afloat financially while waiting for a verdict on their appeals.

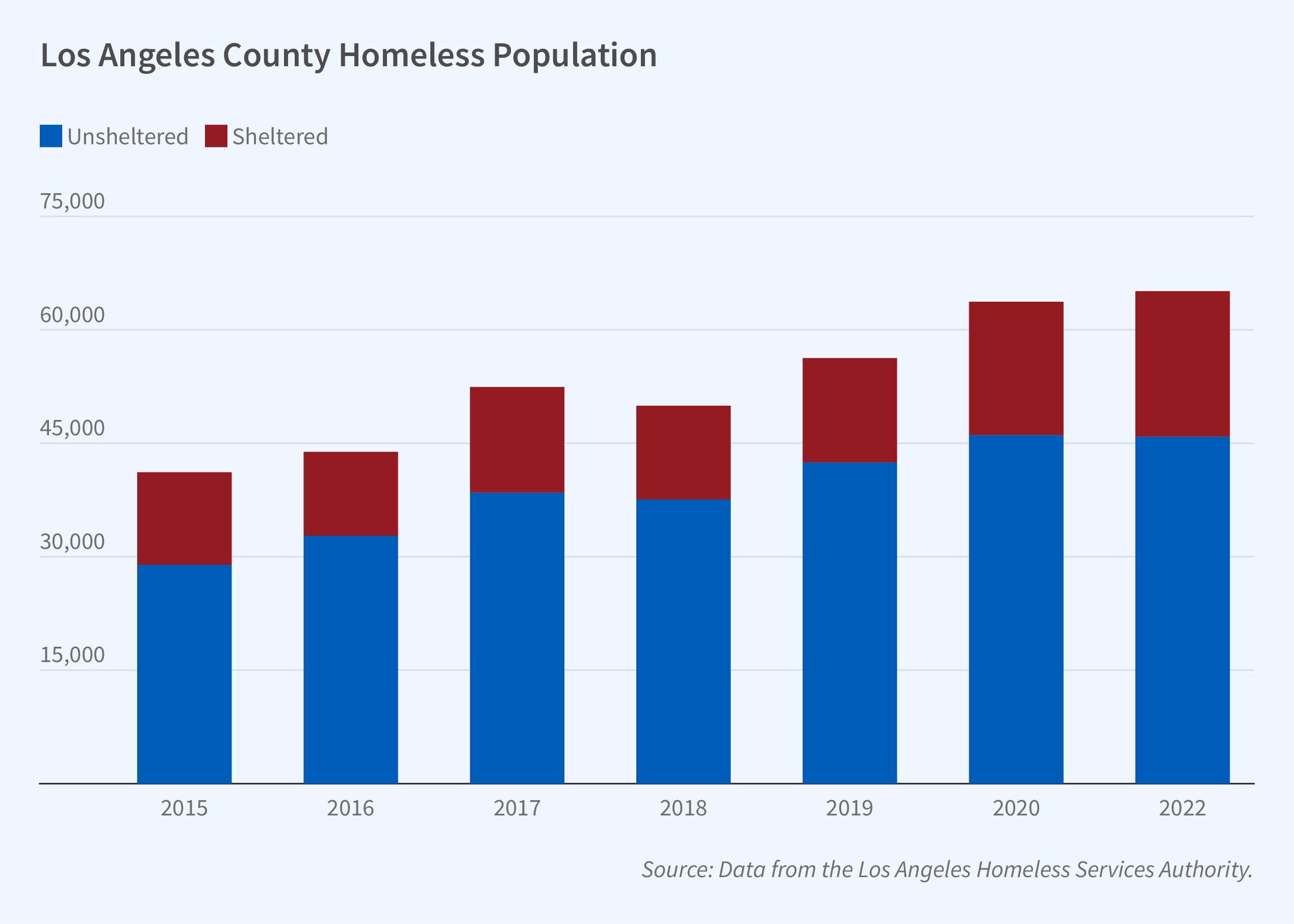

There are more than 75,000 PEH living in Los Angeles County, many with severe physical or mental disabilities. Previous research has documented the barriers they face when applying to the SSA for either Supplemental Security Income, aimed at disabled individuals with limited incomes, or Social Security Disability Insurance, for those with recent work histories. Applications by PEH are approved at only half the overall rate. PEH face multiple application challenges. They often lack access to necessary documents that verify their identity and immigration status. Many interviewees reported struggling to complete application forms, lacked consistent telephone and mail access to SSA and service providers, and received less outside help from informal support networks like friends and family when navigating the process.

By interviewing unhoused Angelinos appealing disability insurance denials as well as interviewing eight service providers trying to help them, the researchers confirm that the barriers for PEH applying for benefits extend to attempts to reverse denials. They find five common challenges.

The first is the preponderance of medical denials, often based on incomplete initial applications. Most of the claimants said they filed appeals after they were deemed medically ineligible, often because they had insufficient medical documentation. Sometimes, documents are missing or of low quality because PEH have nowhere keep them securely. They may not be able to afford the fees to get medical records copied. For their part, some medical providers tend to discount a PEH’s reported symptoms and, overwhelmed by the crush of low-income patients, may produce low-quality records based on very short patient exams. Applications denied because of insufficient medical evidence are often referred to SSA hired doctors for additional consultative examinations, which are sometimes as short as 5 minutes long. One interviewee said of the consultative examination process, “These evaluators are really not examining or helping these people.” One attorney told the researchers, “More times than not, these exams were used to deny benefits.”

A second challenge is the complexity of the application and appeals process itself. Many claimants and providers said it was confusing and especially difficult for those with serious mental health issues, developmental disabilities, and reading difficulties.

The third challenge for PEH involves the process of filing an appeal. They are less likely than other applicants to have consistent access to a mailing address, computer, the internet, a scanner, or even a cell phone. While some qualify for free prepaid phones, these are often stolen and sometimes run out of minutes while holding for an SSA representative.

The fourth challenge involves the difficulties in receiving assistance from SSA staff. Some claimants report receiving conflicting or even wrong information from staff; there were also reports that some representatives were rude. Providers shared that documents they submit to SSA are often misplaced and never processed, with one interviewee saying, "somewhere to 30 percent to 50 percent of documents [submitted to SSA] get lost."

The fifth challenge is insufficient collaboration with formal and informal support resources. Case managers, advocates, and legal aid providers already help claimants gather documents, follow up with the SSA, get to appointments related to their case, and connect with other support services. Providers said that coordinating with the SSA was a significant barrier. Friends and family offer informal support, although they may have a limited understanding of the appeals process. Their direct financial help can sometimes jeopardize claimants’ eligibility for benefits. The article concludes by considering the policy implications arising from these interview findings and input from the study’s community advisor board.

— Laurent Belsie

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.