Medicaid Expansion and Health Care Access for SSDI Beneficiaries

Recipients of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) are eligible for Medicare two years after they become eligible for cash benefits. However, traditional Medicare has substantial cost-sharing and premiums — Medicare Part B premiums amount to over 10 percent of the average monthly SSDI benefit, and coinsurance for physician and other health care services can be as much as 20 percent, with no annual limit on out-of-pocket expenses. While private supplemental plans (Medigap) or Medicare Advantage offer lower cost-sharing, one in five SSDI beneficiaries lacks this supplemental or alternative coverage.

Medicaid is one potential source of supplemental coverage for the disabled population. Prior to 2014, only SSDI beneficiaries with low incomes and less than $2,000 in assets were eligible for Medicaid. Beginning in 2014, state-level Medicaid expansions extended eligibility to SSDI beneficiaries with income under 138 percent of the federal poverty level (regardless of assets). This expansion may have affected SSDI beneficiaries by increasing rates of supplemental coverage, decreasing health care expenses, or promoting substitution away from costly Medigap policies or narrow-network Medicare Advantage plans. Such changes in health care access could affect the health of SSDI beneficiaries, who have a long-term health condition that interferes with their lives and who thus have substantial health care needs.

In Healthcare Cost-Sharing and the Economic Security of Social Security Disability Insurance Beneficiaries: Medicaid Expansion and the SSDI-Medicare Population (NBER RDRC Working Paper 22-04), researchers Philip Armour, Zetianyu Wang, and Claire O’Hanlon estimate the impact of Medicaid expansion on supplemental coverage for Medicare-eligible SSDI beneficiaries as well as the subsequent effects on beneficiaries’ physician visits and health care spending.

The authors compare the change in outcomes for SSDI beneficiaries with incomes below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) between 2013 (pre-expansion) and 2015 (post-expansion) in the 25 states (including the District of Columbia) that expanded Medicaid coverage in 2014, using the change in outcomes for similar beneficiaries in states that did not expand Medicaid in 2014 to capture any general time trends. As an added check, they conduct the same analysis for SSDI beneficiaries with income above 200 percent of the FPL, who were unaffected by the Medicaid expansion. They use data from the American Community Survey, Current Population Survey, and Survey of Income and Program Participation for the analysis.

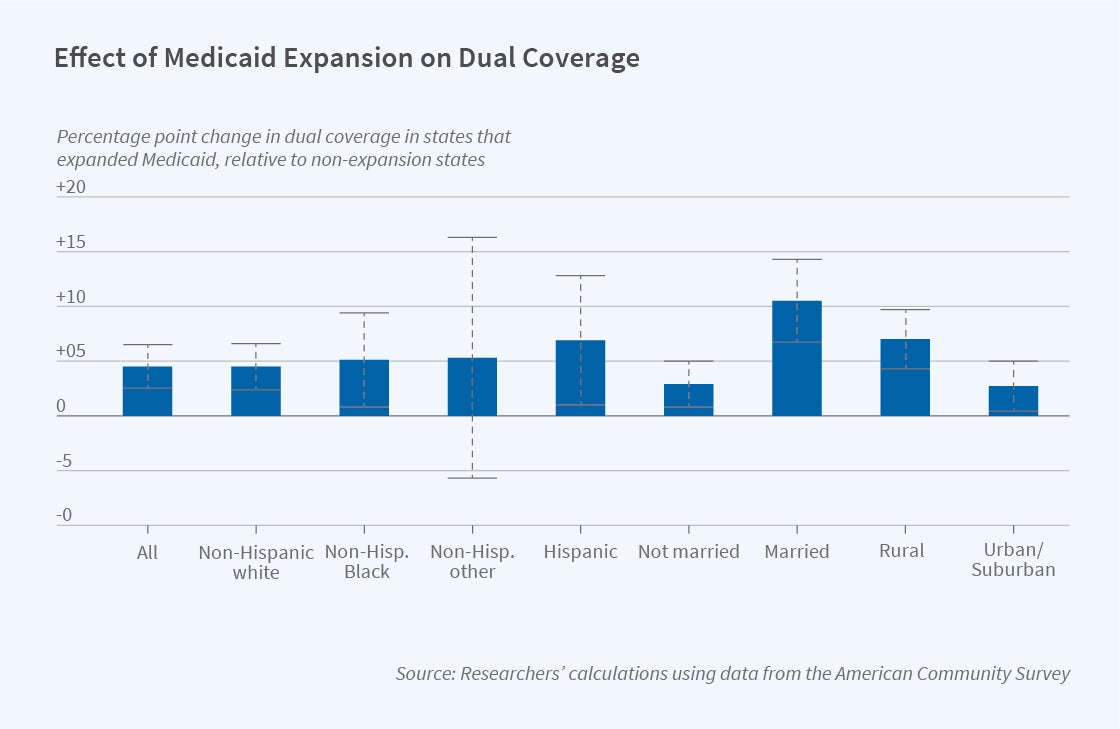

The authors find that the expansion of Medicaid increased the probability that SSDI beneficiaries below 138 percent of the FPL were enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid by 4.5 percentage points. This effect was similar across racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that Medicaid expansion has done little to address existing racial/ethnic disparities in health care access, quality, cost, and use for SSDI beneficiaries. By contrast, the effect of Medicaid expansion on coverage was significantly larger for married individuals, likely because spousal assets counted against Medicaid eligibility prior to the 2014 expansion. The effect was roughly twice as large in rural areas as in urban and suburban areas, consistent with other research finding that Medicaid expansion increased insurance coverage more in rural areas. Turning to the other outcomes, the authors find a measurable decrease in out-of-pocket health care expenditures due to Medicaid expansion, consistent with Medicaid’s limits on cost-sharing, though there was no change in the likelihood of visiting a physician. There is suggestive evidence that spending on health care premiums declined, particularly for rural beneficiaries.

As the authors note, their analysis sheds light on how a particularly vulnerable population — the long-term disabled — is affected by changes in government-provided insurance coverage. As the SSDI population is large and diverse, with over 8 million disabled workers and millions more dependents and survivors, understanding their health care needs and their responses to health insurance coverage can provide insight as to how to optimally design government programs.

The research reported herein was performed pursuant to grant RDR18000003 from the US Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the Federal Government, or NBER. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.