Additional Educational Attainment Reduces Alzheimer’s Risk

Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) represent a growing global health crisis, with cases projected to reach 131.5 million by 2050. The economic burden is substantial: In 2020, ADRD cost the United States $305 billion, with forecasts suggesting a threefold increase over the next 35 years in the absence of effective interventions. While previous research has associated lower educational attainment with increased ADRD risk, establishing causality has proved challenging due to potential confounding factors including childhood circumstances, socioeconomic background, and genetic predisposition.

In Education and Dementia Risk (NBER Working Paper 33430), researchers Silvia H. Barcellos, Leandro Carvalho, Kenneth Langa, Sneha Nimmagadda, and Patrick Turley leverage a natural experiment to investigate the causal relationship between education and ADRD. Using a regression discontinuity design, they examine the 1972 Raising of School-Leaving Age Act (ROSLA) in England, Scotland, and Wales, which increased the minimum school dropout age from 15 to 16 for students born after September 1, 1957.

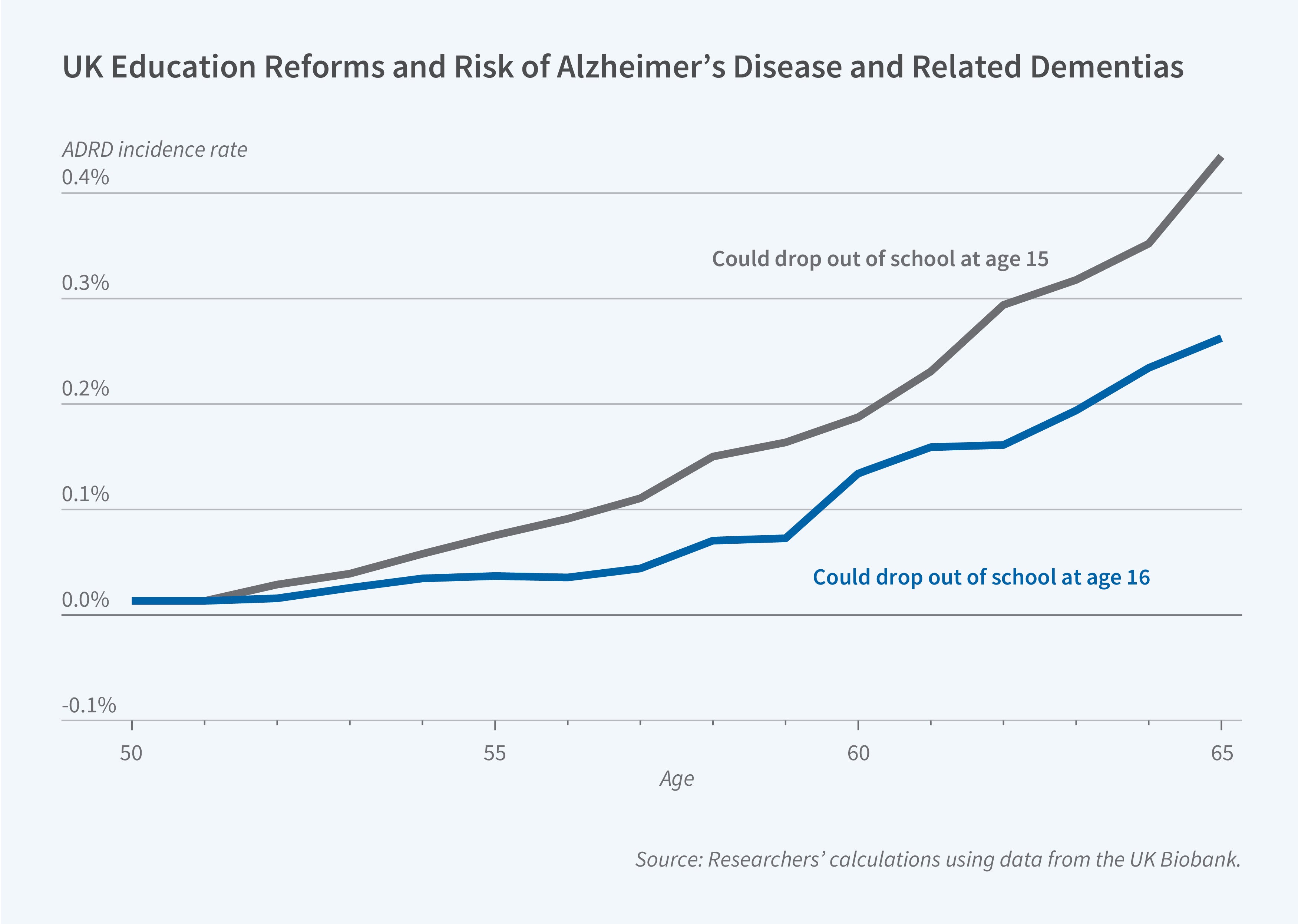

A 1972 reform in the UK that raised the minimum school dropout age from 15 to 16 raised the average years of schooling by 0.14 years. Affected individuals were 0.2 percentage points less likely to develop ADRD by age 65.

The study analyzes data from the UK Biobank. ADRD cases are identified by combining hospital records, mortality data, and self-reported medical histories for the 107,200 participants, with validation studies confirming that the algorithm has a diagnostic accuracy rate of more than 80 percent.

The first affected cohort (born between September 1957 and August 1958) showed a 14 percentage point increase in school attendance until age 16, translating to an average of 0.14 additional years of education. There is no discontinuity in ADRD rates among participants’ parents, who were unaffected by the reform.

The researchers conclude that additional education reduces ADRD risk: Individuals born after the cutoff date showed a 0.2 percentage point reduction in ADRD diagnosis at age 65. The pre-reform baseline rate of ADRD by that age was 0.46 percent.

The point estimate suggests that an additional year of schooling reduces ADRD incidence by 1.4 percentage points (0.20/0.14). The researchers emphasize more conservative values based on the lower bound of their confidence intervals: a reduction of at least 0.09 percentage points in their full sample, and at least 0.23 percentage points among those who left school at 18 or younger.

The researchers use molecular genetic data to construct a “polygenic index” (PGI) that measures genetic predisposition to ADRD and find that education can mitigate the genetic risk of ADRD. They find that the reform diminished the ADRD incidence gap between high and low genetic risk groups from 0.18 to 0.02 percentage points. Among those who dropped out of school at age 18 or younger, an extra year of schooling reduced the effect of PGI by at least 0.08 percentage points, a lower bound estimate.

The study identifies several potential mechanisms through which education might reduce ADRD risk. Reform beneficiaries were 2.2 percentage points more likely to earn £31,000 or more annually and showed reduced rates of key health risk factors such as diabetes (−0.45 percentage points) and stroke/myocardial infarction (−0.59 percentage points).

— Leonardo Vasquez

The researchers acknowledge support from National Institute on Aging grants R01AG078522 (Barcellos), 1K01AG0669991 (Carvalho), RF1AG055654 (Carvalho), R56AG058726 (Carvalho), and R00AG062787 (Turley). They also acknowledge support from the Russell Sage Foundation through grant 98-16-16 (Barcellos and Carvalho).