How Health Disparities Develop over the Lifecycle

In the Netherlands, there are striking socioeconomic differences in mortality among older adults, with a 4.4 percentage point (67 percent) higher five-year mortality rate for 70-year-old individuals with below-median income than for those with above-median income. To better understand the role of chronic disease in these health disparities, Kaveh Danesh, Jonathan T. Kolstad, William D. Parker, and Johannes Spinnewijn develop an index of chronic disease burden in The Chronic Disease Index: Analyzing Health Inequalities over the Lifecycle (NBER Working Paper 32577). This index is a measure of health status that can be measured earlier in life and shows how chronic health evolves with age and differs across income groups.

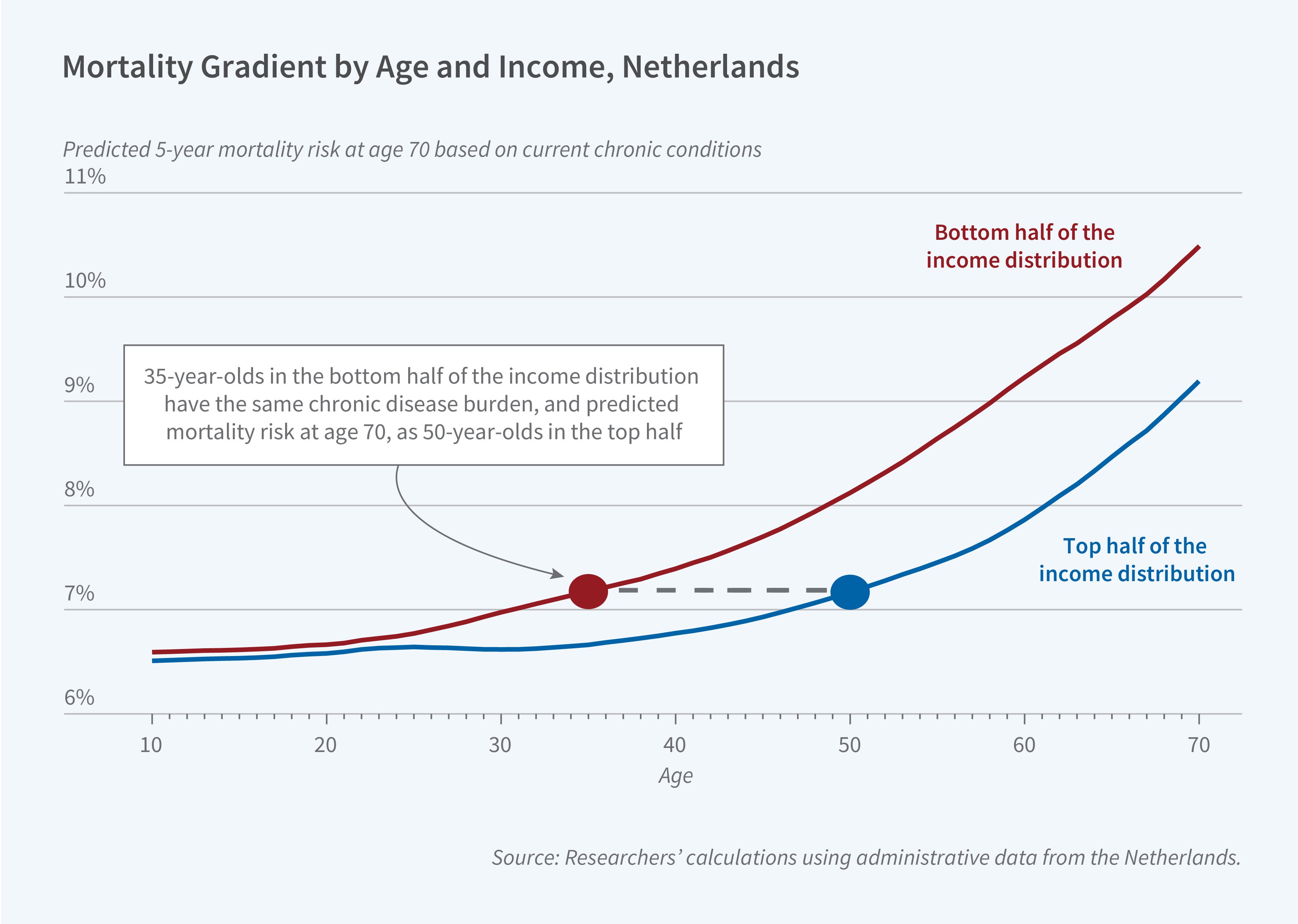

The index predicts an individual’s five-year mortality risk at age 70 based on their chronic condition diagnoses at any age. It is constructed using a 20-year panel of individual-level, administrative data on the health and socioeconomic status of the population of the Netherlands. The researchers identify chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension through insurance claims for medications that are used to manage these illnesses.

Comparing the index for people with above- and below-median income, the researchers show that one-third of the mortality differential is explained by differences in the prevalence of chronic conditions. At age 70, the index is 1.2 points higher for low-income individuals than for high-income individuals. This gap indicates that due to differences in chronic disease burden at age 70, low-income individuals have a 1.2 percentage point higher predicted five-year mortality rate.

Examining the age profile of the chronic disease index, the researchers show that health disparities materialize early in adulthood, decades before the income gap in mortality becomes apparent. While the income differential in the chronic disease index is close to zero at age 20, it grows steadily with age. By age 40, almost half of the disparity in chronic disease burden at age 70 has already emerged.

These findings imply that any level of chronic disease burden affects low-income individuals at an earlier age. Indeed, a typical 35-year-old in the bottom half of the income distribution faces the same chronic disease burden as a typical 50-year-old in the top half.

Approximately 60 percent of the divergence in the index across income groups is due to low-income individuals developing chronic illness at a faster rate, rather than chronically ill individuals earning lower incomes. At younger ages, differences in the prevalence of psychological disorders contribute the most to the socioeconomic gap in the index, while diabetes and cardiovascular disease become increasingly important with age.

The results of this study raise the question of why chronic conditions emerge more quickly among low-income individuals. In a descriptive analysis of potential pathways from income to chronic disease, the researchers find that the growth in a person’s chronic disease index is best predicted by municipality of residence, which may be a proxy for environmental exposure or other place-based differences, and socioeconomic factors such as wealth and education. Observed individual health behaviors, such as smoking, have less explanatory power, especially at younger ages.

— Robin McKnight

The researchers thankfully acknowledge financial support from the International Inequalities Institute and Kolstad thanks the London School of Economics for support through the BP Centennial Professorship that he held during work on this paper.