Tighter Regulation Lowers Targeted, but Not Overall, Opioid Use

In response to concerns about misuse of two commonly-prescribed opioid medications, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) tightened the rules for prescribing them in 2014. The additional restrictions were effective in reducing use of the targeted drugs, according to Competitive Effects of Federal and State Opioid Restrictions: Evidence from the Controlled Substance Laws (NBER Working Paper 27520) by Sumedha Gupta, Thuy D. Nguyen, Patricia R. Freeman, and Kosali I. Simon. However, substitution towards other opioid medications occurred to such a degree that the DEA’s actions had no impact on total opioid prescriptions.

The DEA has the authority to designate prescription drugs that have a known risk of abuse as controlled substances. It places each controlled substance in a tier, or “schedule,” that reflects its medical use and its potential for dependence and misuse. The most strictly regulated substances are those in Schedule I, such as heroin, which have no accepted medical use. The least strictly regulated are those in Schedule V, such as mild narcotic cough medicines, which are considered to have minimal potential for abuse. To shed light on the effects of this system, the researchers focus on recent changes to the controlled substance classifications of two opioids: tramadol and hydrocodone combination products (HCPs).

On August 18, 2014, the DEA first designated tramadol — which was previously non-controlled and accounted for 15 percent of US opioid sales — as a Schedule IV controlled substance. This classification means that prescriptions are valid for only six months, with no more than five refills permitted during that period. In addition, all controlled substance prescriptions must be reported by the prescriber through their state’s prescription drug monitoring system.

Seven weeks later, on October 6th, 2014, the DEA “up-scheduled” HCPs from Schedule III to a more restrictive Schedule II classification. HCPs are medications that combine the opioid hydrocodone with non-opioid substances such as acetaminophen. Prior to this classification change, HCPs accounted for 46 percent of US opioid sales. As a result of their Schedule II designation, prescriptions for HCPs are valid for only 90 days, refills are prohibited, and the original prescription must be physically presented at the pharmacy.

There are several reasons to expect that these scheduling changes would reduce utilization of the targeted drugs and, potentially, increase prescriptions for less-controlled substitutes. Prescribing a more controlled substance may be relatively inconvenient for the patient and provider. The limits on refills, for example, necessitate more frequent office visits. In addition, the stricter classification may signal to providers that the medication carries greater health risks than less-restricted alternatives.

The researchers use a large sample of commercially-insured patients and Medicare Advantage enrollees to examine prescription drug use before and after the changes. Their research strategy relies on the idea that the precise timing of the changes was unanticipated and binding. They assume that, in the absence of these DEA decisions, prescriptions for tramadol and HCPs would have trended smoothly around the dates of their re-classifications. The researchers interpret any breaks in the trends that coincide with these dates as impacts of the re-classifications.

The researchers report that HCP prescriptions were unaffected by the tramadol decision, but fell by an estimated 13 percent after the HCP decision. There was also a coinciding reduction in the number of doses per HCP prescription.

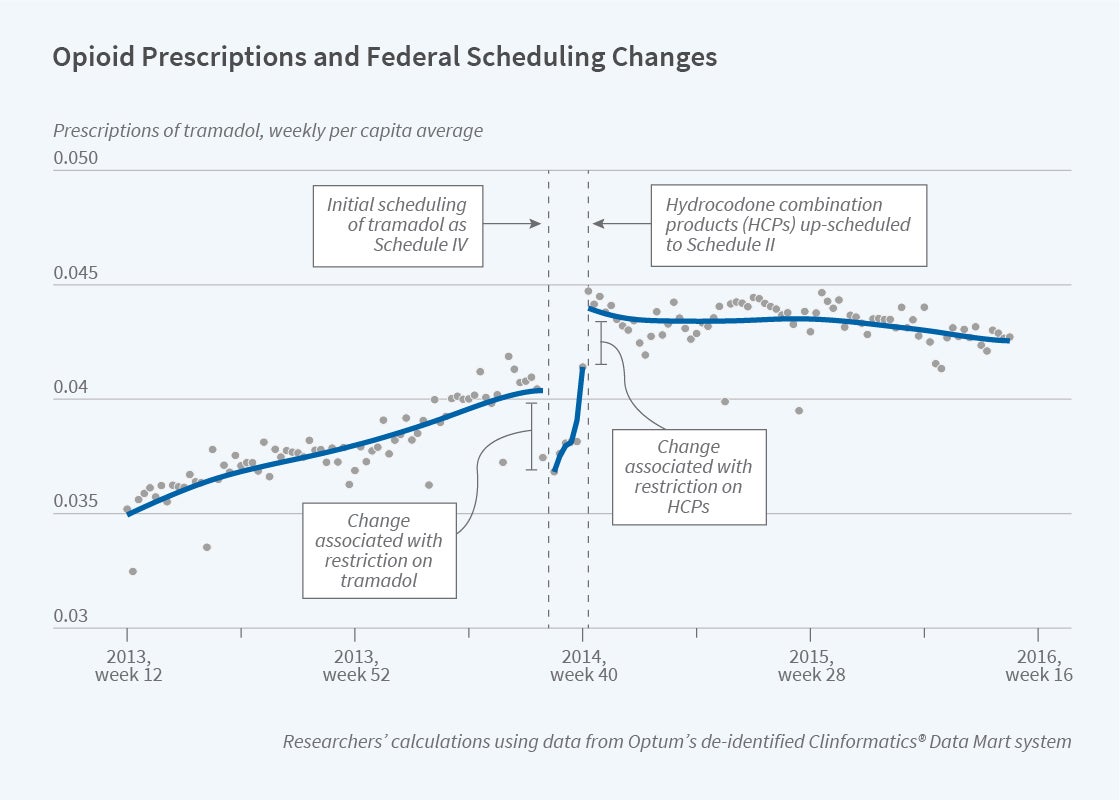

The DEA’s actions affected tramadol in a more complex way, as seen in the figure. Tramadol prescriptions were influenced both directly, by the tramadol decision, and indirectly, by the HCP decision. Prescriptions for tramadol fell by an estimated 5 percent immediately after it was designated as a controlled substance, although sales rebounded over the following weeks. Then, tramadol prescriptions abruptly increased by 10 percent in response to the increased restrictions on HCPs, as patients switched to less-restricted substitute medications.

The researchers document a similar pattern of substitution, with a 28 percent rise in prescriptions, for other competing opioids that were subject to less regulation than HCPs. On net, the decrease in HCP prescriptions was fully offset by increased prescriptions for tramadol and other opioids, yielding no overall change in prescription opioid use.

In a complementary analysis, the researchers examine earlier state-level decisions to classify tramadol as a Schedule IV controlled substance prior to the federal government’s decision to do so. Eleven states took this step, beginning with Arkansas in March 2007. Interestingly, these state policies had similar impacts on tramadol prescriptions as the initial impact of the federal action, with sustained 5 percent declines in prescriptions. These findings suggest that it can be effective for state governments to use controlled substance classifications to increase regulation of prescription drugs within their states.

The researchers conclude that, while stricter regulation of prescription drugs — at the state or federal level — can reduce access to medications with known potential for misuse, “there are unintended substitution behaviors that may unravel the deeper intention of the policy.”

The researchers acknowledge support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant DA039928) and the Indiana University Grand Challenges Initiative.